It's a man eat dog world

I have a new rule I’m workshopping. I call it the 25% rule. Here it is: Movie lovers should only do a deep, chronological dive on a director’s filmography if they’ve seen at least a quarter of their films, preferably a sampling of their most representative and influential works. Of course, you might not identify “representative and influential” until you’ve taken the plunge, but you usually know by reputation, or you can check They Shoot Pictures or Letterboxd’s most popular for the directors. The 25% rule may be infeasible if I ever decide to go for, say, John Ford or Ernst Lubitsch or Alfred Hitchcock, which would require I’ve seen a dozen or more films before I begin a chronological survey. Then again, it might be good to know you really like a classic director before trying to commit hundreds of hours to becoming a completionist.

For example, I recently watched Richard Linklater’s amateur film, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, and it deeply fascinated me, but mostly because I could see connections to Before Sunrise and Dazed and Confused, little germs of ideas and fascinations that would grow as Linklater’s filmography developed. If I had jumped in blind from the start, like I did for my Denis Villeneuve watch-through, I’d have been more baffled than intrigued. I wouldn’t have known what to look for or had anything interesting to say about it. (Analogously, I think I’d view Villeneuve’s first few films totally differently now that I properly understand where he was headed with Sicario and Dune and such.)

This new rule of mine is relevant because, as I write this, we are in the tail of winter and in the midst of a drought of exciting new releases. Dumpuary is in the books; Febuscary has passed; Fartch is about half-finished. As a critic, I try to use this time to fill the gaps on some director I am curious about, but never reviewed studiously or enthusiastically. I tend to target filmmakers with new films recently released or coming soon.

The 25% rule puts me in a good place for Bong Joon-ho, who just released his eighth film. I’ve seen Parasite (loved it) and Snowpiercer (unsure of it), so I’m a quarter of the way there. I caught the new Mickey 17, too. It’s enough to give me a sense of a couple of Bong’s preoccupations (e.g. sure sucks to be poor) and to know where this is all headed. And so here I am with Bong’s debut film, Barking Dogs Never Bite, kicking off a Bong watch-through.

That’s an awful lot of navel-gazing and prelude, but it mirrors the way I approached the film: to understand where Bong came from. What he was like before he was Korea’s most famous director? Sometimes early works of artists offer an intimate lens on the person. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that songwriters like Bruce Springsteen and Taylor Swift shift away from autobiographical material and towards a more literary style featuring imagined, archetypal characters in their later albums. Once you’re on the cover of Rolling Stone, it’s hard to remember what it’s like being small and ordinary. Once you’ve directed a movie starring Chris Evans or won Best Picture, a struggling academic might be no more accessible to you than aliens and clones.

Bong released Barking Dogs Never Bite when was barely 30 years old. He grew up middle class in Seoul, went to film school, and then crewed on a few small film projects before writing and directing his own feature. It was a long-germinating idea of Bong’s from an experience he had as a kid. He was exploring a building when he encountered a dead dog. The sight startled and frightened him. He disliked the indignity of its corpse lying outside, exposed to the world. He worried someone might steal it and eat it. Out of that image — an animal lying lifeless, its carcass slowly decaying, its incongruity with modern life pregnant with existential pain and ordinary tragedy — comes not just a curio of a film but a career that would dig deeper and deeper into the themes the image suggests. On an immediate level, many of Bong’s films advocate for protecting vulnerable nature, especially animals. Symbolically, a dead dog ignored by busy world is a symbol for being left behind or degraded, especially by the cruelties of capitalism against the impoverished. (Speaking of Bruce Springsteen, he similarly pondered the experience of stumbling upon a dead dog in the opening verse of his masterpiece “Reason to Believe.”)

And yet Barking Dogs Never Bite is not an especially heavy film. It has a cynical undercurrent, but it would not be out of place on the Sundance or SXSW indie circuit. It is a dark, low budget farce about the crappy lives of the low-income residents and workers of an apartment complex who make each other’s lives even crappier. Specifically, it uses an investigation into a series of missing pet dogs as a lens into the bleak, boring lives of its characters, each of them trying in vain to get their big break.

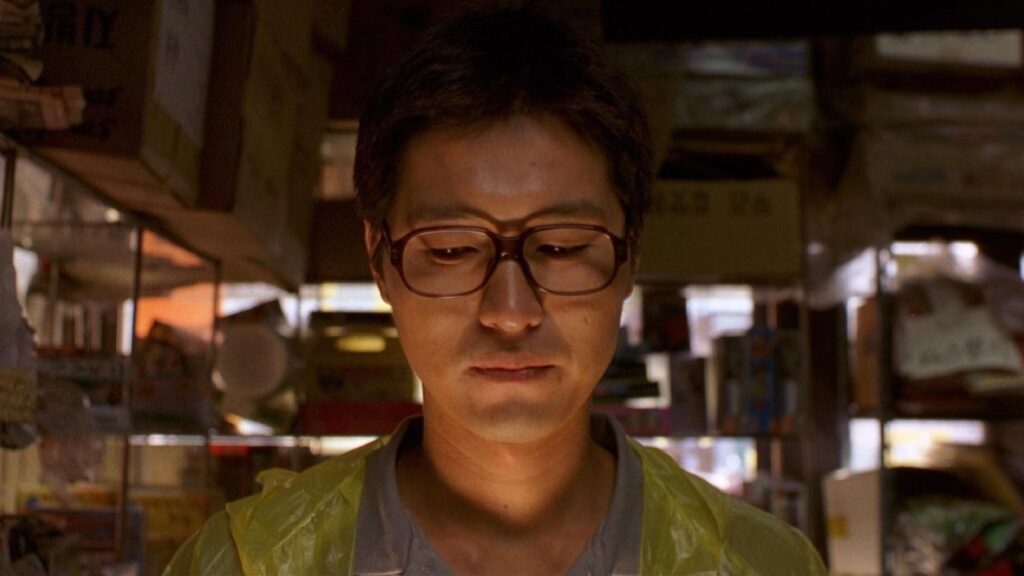

Ko Yun-ju (Lee Sung-jae) is an unemployed man hunting for a job as a professor at nearby universities that will pay enough salary to let him, his pregnant wife (Kim Ho-jung), and their child-to-be live in comfort and ease. The problem is that his buddy, who is already a professor, alerts him that the deans only hire people who bribe them. Yun-ju does not have the money to offer this bribe. It’s a real capitalistic Catch 22 — you need money to get money. The futility of Yun-ju’s job hunt is emblematized and exacerbated by an annoying dog yapping nonstop in a nearby apartment as he conducts his phone inquiries and interviews. He makes it his mission to take vengeance against this annoying dog.

When he finally tracks down and kidnaps the dog from his kindly old neighbor (Kim Jin-goo), he considers killing the dog, but gets cold feet and instead locks it in the basement, presumably to be rescued within a day or two. This kicks off a chain reaction of silly coincidences and mistaken identities that results in a second and third dog’s disappearances, with lots of dramatic ironies and nasty punchlines.

Meanwhile, Park Hyun-nam (Bae Doona), a maintenance worker and errand runner for the apartment complex, decides that she’ll solve the mystery of the vanishing dogs and become a local hero like the people who get covered in the human interest stories on news broadcasts. She’s constantly on the tail of Yun-ju, who she separately meets and gets to know, but never quite deduces that he’s the original dog kidnapper. In a different story, there would be a romantic connection between Hyun-nam and Yun-ju, and we get a few moments of chemistry between the pair, but Bong would rather this be a satire than just another canicide romcom.

Bong’s script is actually quite tight for a first effort, with good comic structure of cascading incidents that click together like threads of a zipper. It’s like he watched a bunch of screwball comedies and filtered it through his own world and sensibilities. There are a couple good punchlines, and Lee really sells Yun-ju’s growing despondence at his scenario, but the biggest laughs come from the cleverness and timing of some of the plot’s cruel turns. The big knock is the slow, contemplative ending — a Bong tradition, but one that simply doesn’t fit here. The whole third act slows down too much, resulting in a runtime padded by ten or fifteen minutes.

Despite the sturdy script, it’s obvious that Bong’s interests lie outside of classical comedy. There’s a sense in the direction he’s already growing a little bored of ordinary human interaction. He devotes a lot of attention to stylization and camerawork that has little bearing on the rest of the story or goes above and beyond the narrative needs: Early on, a janitor with a bloody butcher knife slowly stalks a character like we’re watching a slasher. Later, while Yun-ju is out on the town to network with potential employers, Bong saturates the film in disorienting greens and oranges like Yun-ju’s is visiting an alien civilization. In another scene, a dog vanishes in the pesticide fumes of gardener, smoky and silky like its train steam in Brief Encounter. Perhaps most memorable of all are two slapstick chases through the walkways of the apartment complex, both of which include abrupt and cruel jolts of violence.

Bong’s instincts are good, but his craft is not fully developed in his debut. It’s like watching an athlete doing his first warm-ups of the day — there are glimmers of technique and prowess, but mostly a lot of motion to get the juices flowing. Bong controls the tone well — it’s frankly a steadier flow than some of his later films — aided in part by a fun jazz score by Cho Sung-woo. No future Bong films have the same style of soundtrack, but it does a lot to maintain some playfulness.

I will not get carried away; the film’s enduring appeal is primarily in the context of being the debut of a Best Director-winning visionary, possibly the most-revered Asian filmmaker of the past decade. But as a quirky, standalone film, I think his first film still works, with both some bark and some bite.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.