Side F/X may occur

Rollie Tyler (Bryan Brown) is the best practical special effects artist in the business — or at least in the movie’s slightly heightened 1986 version of Hollywood. Nobody makes a squib pop like him. One day, the Department of Justice comes knocking. They have a proposition: Stage a convincing public assassination of a mobster-turned-informant so they can shuffle him quietly into witness protection. But it’s not just about designing the illusion—they want Tyler to pull the trigger himself. He’s hesitant, but he’s also a consummate professional.

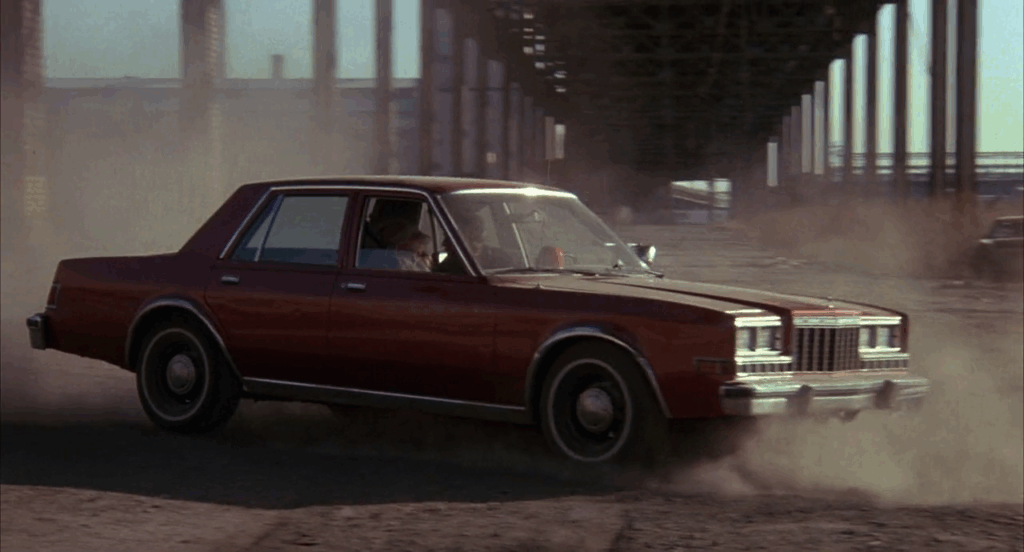

Tyler agrees, rigs up a dazzlingly staged mob hit in a restaurant. He fires the gun. So far, so good — until the informant actually dies. Tyler realizes too late that the blanks weren’t blanks, the scenario was altered, and he’s now the lead suspect in a very real murder. The men who hired him have framed him and are trying to kill him to tie up loose ends. From here, F/X shifts into chase mode: Tyler goes underground, armed with only his movie magic toolkit and his wits. Can he clear his name? Maybe exact some revenge?

You gotta admit it: That central hook is dynamite — an action-thriller where the protagonist uses his behind-the-scenes movie tricks to survive a government conspiracy. The scenario is a smidge convoluted, but appealingly so: It’s a rich with potential for sleight-of-hand reversals, prop-based mischief and set pieces, and perhaps even knowing winks at the machinery of movie-making.

Alas, F/X doesn’t fully capitalize on that promise. It’s never at risk of becoming a bad movie, mostly functionally executed, but a lot of potential is squandered. The more the story unfolds, the more the film seems to settle for generic cop procedural rhythms instead of digging into the loopiness and the razzle-dazzle. It ultimately lands somewhere between inventive thriller and plain old ‘80s cable filler — the kind of film, in fact, that Tyler’s effects are supposed to transcend.

F/X’s opening scene is one of those fakeouts common in movies about filmmakers or actors, a blood-spattered shootout that’s quickly revealed to be one of Tyler’s effects sequences. It does a good job calibrating us on the upcoming action and priming us not to trust what we see — a proposition that F/X leans on a couple times, but could have gone for once or twice more, in my opinion. We get to know Tyler in the opening scenes in part through his live-in workshop, which oddly seems to feature more B-movie monsters than action movie props. (In-universe, this is quickly explained as being the type of movie Tyler used to make and that made him famous, but doesn’t make anymore.)

The best stretch of the film is probably the lead-up to the fake hit: a heist-movie-style montage of planning and prep, with Tyler setting up his blood packs and wireless triggers on a swaggering Jerry Orbach as the mob informant. The assassination itself is a clear homage to the restaurant hit in The Godfather — so blatant, in fact, that F/X calls it out. After that, though, the tone shifts. But once the frame job kicks in, the movie loses some of that identity. Instead of going all in on a rogue movie magician setting up traps and illusions, F/X pivots to a split-perspective crime thriller.

Enter Detective Leo McCarthy (Brian Dennehy), who shows up to investigate the ensuing body count and introduces a whole separate, entirely unnecessary thread: a run-of-the-mill gruff-cop procedural. I held out hope that McCarthy’s subplot would circle back into worthwhile, its simply adequate policework offering some sort of narrative deflection for the cat-and-mouse between the feds and Tyler in the rest of the film. But it never does in any meaningful way, and it remains deeply generic. (When Community spoofed ‘80s cops movies, Abed pretending to be a police chief kicking a detective off the force could be pulled about 80% verbatim from a scene here.) McCarthy’s scenes not strictly bad (mostly Dennehy walking into buildings and shouting at people), except in opportunity cost to the more interesting movie around it.

Fortunately, F/X remembers its premise in time for the climax. The final twenty minutes deliver a rushed promise-of-the-premise, as Tyler rigs up a series of booby traps and fake-outs using his movie gear against the group that conspired against him. It’s not quite a heist payoff, but it scratches a similar itch — Tyler turns into a one-man guerrilla infiltration crew, improvising with glues, masks, and spring-loaded mayhem. It’s all a bit removed from reality — he basically becomes goblin-mode Kevin McCallister from Home Alone, a superhero version of the effects artist introduced in the first act — but the spectacle is fun, and it’s a high-energy finale.

Brown as Tyler offers a chilly persona with a barbed edge. I looked it up and was not surprised that he’s Australian — those Aussies have a dangerous glint in their eye. Pretty much everyone else is exactly replacement level, though Dennehy registers more as a grumpy police chief than an off-the-range detective. But the cast overall fades into the commotion surrounding them.

Again, the whole thing is fine, but no better than. There’s a bit of clumsiness throughout. For example, one love interest abruptly dies without emotional baggage, only for another one to appear a few scenes later and serve pretty much the same role. None of it is movie breaking, but every dopey decision and slow cop scene weighs down a strong premise. That’s =the real “special effect” of F/X: At first glance it seems like it should be a cult classic, but it’s a trick of the eye; in reality, it’s a merely decent Sunday afternoon cable TV flick.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “F/X (1986)”

I told you it was disappointing!

The more I’ve thought it about it, the more dumbfounding it is how it’s using its elements: you’d really think Dennehy would be the cop after Brown and realizing that this doesn’t add up, rather than just sort of colliding with his case on a tangent. The conspiracy plotting is also pretty weird given how the world is not actually against Brown–I can’t remember exactly what the other NYPD detective’s deal is, but I would assume he would be equally open-minded considering the hash the DoJ’s agents have made of tying up Brown’s loose ends already–and it’s always really just a few rogues in the DoJ. It is not super-surprising to learn it was from first-time screenwriters, and the director “was not impressed” by it, doing the film mostly just to broaden his brand into masculine car-chase stuff. It is aggravating because the first act or act and a half or whatever, everything through Diane Venora’s startling early death anyway, is really aces.

You were right! I didn’t mention it here, though I think you did in your Letterboxd review, but this is one of the softest LA-as-NY renderings I can recall.

Yeah I guess it’s mostly a screenplay problem, isn’t it? I think you’re right that it’s not clear that Tyler would be a “bad guy” — he killed a notorious gangster. There’s a few too many layers of deception here for any of it to really register — an ex-mobster… ratting out the mafia… who is subsequently assassinated… except not really… except yes really… except (spoiler last twenty minutes)… and most of that is orchestrated by a few rogues and obfuscated from the NYPD and the public. Kind of confusing and unintuitive.

I wonder if the fundamental problem with this film is that it was put together without a next-level Special Effects Wizard?

Also, Bryan Brown is something of a treasure, possible because he keeps appearing in films that would be far less entertaining without him.

A few more fun effects would definitely spruce it up, especially in the middle act!

I’ll definitely keep my eye out for Brown, though according to Letterboxd I’ve seen several things with him already. He’s stuck around, apparently!