Gangs of London

Season 3

Episode 8

"Nobody wins. Nobody ever fucking wins."

Of course it was the Investors. It had to be.

Something I’ve not really delved into so far in this series of reviews is Gangs of London’s politics. It’s not a show that makes a point of hammering home a message, but I’m of the persuasion that all art is political, whether it wants to be or not. Any story – any piece of media that wants to communicate meaning – has to start from a basis of shared assumptions. If you want to make an epic crime drama set in modern-day London, then you necessarily have to make your assumptions available to your audience, about what is “London”; what is “crime”; what is “modern-day.”

To wit: S3 E8 begins with Cornelius beating Ed Dumani like a rented mule after his treachery was exposed last episode, while Billy, Marian, and Luan watch dispassionately. Ed’s resilient under torture – he’s had practice – but he breaks when Marian gives Luan the go-ahead to hunt down Shannon and Danny, and kill them. As Elliot arrives, Ed tells them the identity of the people behind the fentanyl spiking; the proprietors of the corporate logo on the documents Naomi was killed for, the one that looks like a hybrid of a “V” and a “W.”

“Isobel Vaughn,” Ed grudgingly confesses, in return for the safety of his daughter and grandchild.

“Who?” Elliot asks (echoing my own sentiments).

“A businesswoman,” Ed says, doing the bare minimum to clarify.

“An Investor,” Elliot replies, picking up on Ed’s subtext.

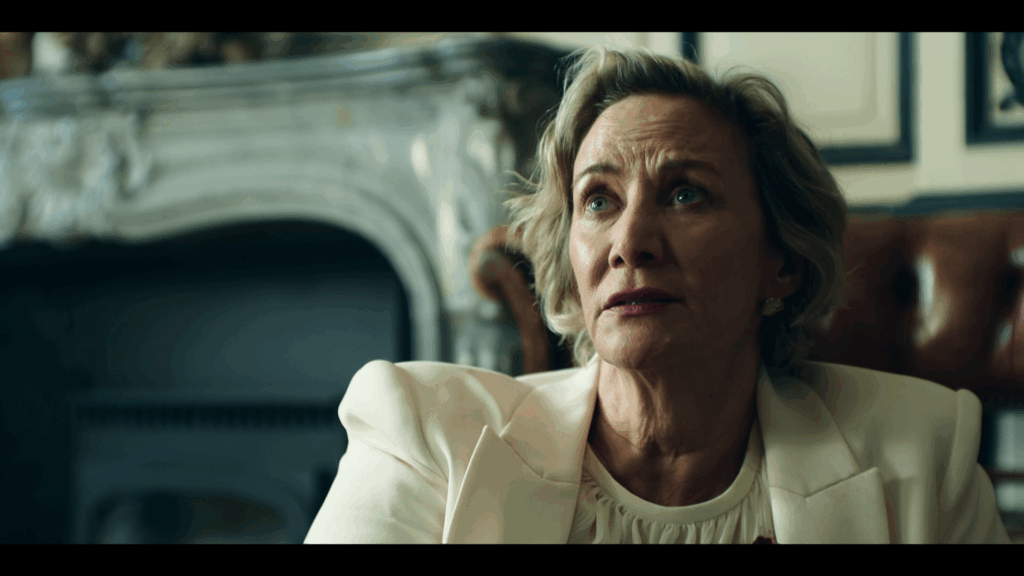

Yep: Isobel Vaughn (played by Janet McTeer) is the ultimate villain behind the fentanyl poisonings. She has farms in Myanmar, Peru, Pakistan and Türkiye, where she’s spent the last decade developing high-yield cultivars of poppies and coca, even as her underling, Henry, groomed Simone for her political career, laying the groundwork for drug legalisation in the UK which her company will be uniquely suited to profit from. The cancer of the Investors’ influence in London – in remission ever since the purges Sean and Koba set in motion in S2 E6 – has recurred with a vengeance.

The cancer of the Investors’ influence in London – in remission ever since the purges Sean and Koba set in motion in S2 E6 – has recurred with a vengeance.

In the words of another TV show with long-term plotting almost as wonky as Gangs of London’s: “all of this has happened before, and all of this will happen again.” Lives in London were destroyed and cycles of violence inflamed by profiteering ghouls thousands of miles distant, for whom 600 deaths by overdose are just a rounding error on a spreadsheet.

Gangs of London’s politics in a nutshell, then: it’s pro-multiculturalism, but opposed to economic globalisation.

It’s a worldview that’s peculiarly consistent throughout all three seasons: honestly, more consistent than the characterisations of the main cast. The show’s underlying assumption is that it’s possible for communities from different national and ethnic backgrounds to peacefully coexist. Prior to Finn’s assassination in S1 E1, it’s implied that the various gangs from Pakistan, Kurdistan, Albania, Algeria and Ireland are essentially able to get along; that their interrelationships are stable, even if they’re not necessarily friendly. None of the conflict in Gangs of London proceeds from sectarian tensions. Even Lale, a character who’s committed to an explicitly political cause – Kurdish autonomy – hasn’t spent any of her screentime directly prosecuting that cause. Most of the action she takes throughout the series is motivated by her grievances with Asif, which are entirely personal, not ideological.

(It’s worth noting that Pulse Films CEO Thomas Benski is himself a French-Brazilian immigrant who moved to the UK as a teenager in 1998. For that matter, lest we forget, the series was created by Gareth Evans, who grew up in Wales, and is multilingual, married to an Indonesian-Japanese partner, and spent the better part of a decade living, working, and raising a family in southeast Asia, over 9,000 miles from where he was born.)

In Ed’s eulogy for Finn, way back in the show’s first episode, he characterises the generational partnership between the Wallace and Dumani households as a bastion of solidarity between minorities. “No blacks; no Irish” was the refrain that summed up the barriers that he and Finn faced while growing up as immigrants in the 60s, and which they fought to overcome together. It’s a hoary old trope, and the abiding explanation for organised crime as a sociological phenomenon; enclaves of minorities disenfranchised by the mainstream, coming together in their shared disenfranchisement to create a sort of parallel, illicit economy where they can flourish together.

Of course, Ed was being disingenuous when he delivered that eulogy back in S1 E1, just as he was being disingenuous when he feigned shock at finding the Belgian beer kegs in Elliot’s house. He was already in bed with the powers that had Finn assassinated, and he was in bed with the same powers again when he ordered for Sean to be killed.

The illicit, parallel economy of organised crime is vulnerable to the same perverse incentives of international capitalism as the mainstream economy. It can be coaxed and prodded by bad actors; communities torn apart and set at each other’s throats in the scramble to be part of the in-group.

It’s hard to feel any sympathy for Ed when Marian finally blows his brains out in this episode.

It’s hard to feel any sympathy for Ed when Marian finally blows his brains out in this episode. The confirmation that he ordered Sean’s death on his own initiative is the final nail in his coffin: he’s exhausted all of his second chances, and the Wallace dynasty is quite within its rights to be done with him. But there’s something that feels uncomfortably plausible, here in 2025, about his willingness to sell out his oldest friends and allies. The people at the top, the ones calling the shots, are all a bunch of grifters and hucksters. That being the case, isn’t it in a guy’s best interests to be a grifter and huckster himself, and be allowed a seat at the table?

Don’t get me wrong: the introduction of Isobel Vaughn as an antagonist at this late juncture is pretty lame. Not that it was badly foreshadowed; the recurring motif of the Vaughn Alliance logo throughout the season made it clear there was a common thread linking Ed, Asif and Henry, one more still-deeper stratum to the conspiracy. And Janet McTeer does a fine job with the part, in her limited screentime: aristocratic and businesslike, able to rationalise her misdeeds when interrogated with such cool intelligence that she almost makes it sound persuasive.

But during her scenes, I was thinking back to what I wrote about the Investors as villains when discussing S2 E5. The Investors derived their potency in Seasons 1 and 2 from their vague, numinous quality; the way that their members were never represented on screen; not identified by name; not identified by face; not even identified by individual agendas; always treated as a kind of aggregate force of will, effected through intermediaries. The introduction of Isobel Vaughn immediately collapses all of the mystique that made the Investors compelling. By giving her a face and a name and a history and a physical presence in the show’s universe, the Investors become just people, vulnerable to involvement in fistfights and shootouts.

I might have been willing to forgive the decision to make one of the Investors corporeal, if the mission to unseat her felt suitably epic. I can imagine a version of this season finale where Elliot, Marian, Cornelius and Luan launch a combined assault on Vaughn’s country estate shareholder meeting, and drag the truth out of her, inch by bloody inch. A British version of the finale of A Better Tomorrow II.

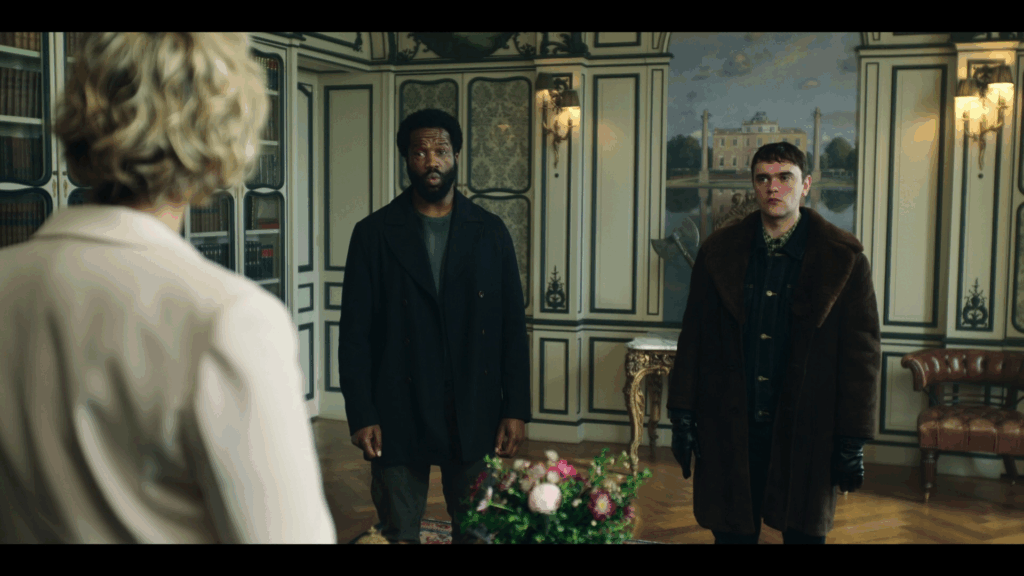

But, unfortunately, nothing happens that’s anywhere near that awesome. Instead, Elliot and Billy go together to the meeting, in what might be the easiest infiltration mission ever depicted on TV. At the gates to the estate, Elliot hands the guard the invitation he got from Ed, and identifies himself as Ed Dumani. He’s waved through. (Apparently, the security at this event doesn’t extend to photo ID. And for that matter, Billy is just allowed to come along with him, no questions asked, so I guess this congress of ultra-rich criminals operates on an RSVP basis, like your cousin Vera’s wedding.)

I think, overall, I like Gangs of London’s third season better than its second. This is mainly because – as I’ve said before – it has an internal consistency that Season 2 lacks. It has throughlines; plot points established in episode 1 that pay off in episode 8, in ways that bespeak rigorous planning and foresight.

I think, overall, I like Gangs of London’s third season better than its second.

Where Season 3 trails Season 2, though, is as spectacle and as action. (Let alone the first five episodes of Season 1, which feel like an unattainable ideal by this point.) Elliot and Billy step into the boardroom where Vaughn is buttering up her shareholders; they both look very tired and pissed-off and are dressed wildly out of step with the occasion’s sartorial standards.

Vaughn has the bright idea to forestall her shareholder meeting and invite Elliot (who is obviously not Ed Dumani) and Billy up to her office for a private conference. (Some of the decisions she makes in this episode, frankly, make me wonder if she’s qualified to operate a deep fryer, let alone a hundred-billion-pound market manipulation gambit.) Predictably, her explanations for why she murdered their loved ones (and hundreds of others besides) don’t go over very well. Billy and Elliot fight and kill all four of her bodyguards, the sounds of gunshots seemingly alerting no-one downstairs.

It’s not a terrible fight scene, by any means – the choreography is solid, and the editing is mostly clear. I like the detail where Billy uses his prosthetic arm to intercept the swing of an incoming cleaver. But, c’mon. For all the shit I gave Season 2’s finale, the construction site battle between Elliot and Sean at least had some operatic gravitas to it. Here, in the Season 3 finale… Elliot and Billy brawl with a handful of randos for a couple of minutes, and that’s the episode’s big centrepiece??? It feels like a fight scene included by mandate; because Gangs of London has to have action beats, even if the writers and directors and producers resent them.

(I suppose it behooves me to mention that, in the course of the melee, Billy stabs Henry to death. Good riddance to that unctuous wanker.)

The sense of showmanship and spectacle that once characterised Gangs of London feels like it’s fallen by the wayside. What I do appreciate about this season finale is how it retrenches and reframes the events of its story as a tragedy.

What I do appreciate about this season finale is how it retrenches and reframes the events of its story as a tragedy.

Elliot has Vaughn at his mercy, already bleeding from a gunshot wound inflicted by Billy. However, when he namedrops his wife and son, Vaughn’s eyes light up with recognition, and she launches the last, big, bombshell plot twist of the season. Naomi wasn’t working to bring down Vaughn’s operation; rather, Elliot’s wife was working for Vaughn, a true believer and passionate advocate for drug policy reform. Far from being killed for trying to expose Vaughn Alliance’s operations, she was killed by the Wallaces, for threatening their profits from the illegal drug trade.

Billy, of course, vehemently denies this. Elliot backs out of the room, swearing to kill whichever of the two parties who is lying to him.

The viewer might justifiably be as confused as Elliot at this point, but the truth of the matter swiftly becomes clear. Billy confronts Marian after she kills Ed, and presses her about the lawyer they killed seven years earlier. Vaughn was telling the truth, and Billy knew it, and he was consciously lying to Elliot. In fact, not only were the Wallaces responsible for killing Elliot’s family; Billy was personally present at the scene. In a remarkable bit of narrative sleight of hand, it turns out that Billy – not Zeek – was the hooded figure who retrieved the folder from the overturned car, leaving Naomi and Samuel to burn on Finn’s orders.

(I went back and reviewed the prologue sequence in S3 E1 shot by shot, and it is extremely cleverly edited. Zeek definitely drove the truck that T-boned Naomi’s car, but he never got out of the cab. The cutting makes it look like he and Billy were the same person so convincingly that it even sort of fooled me on a rewatch, knowing the plot twist. The Treachery of Images is surprisingly powerful.)

I have serious plausibility concerns about this plot twist. For one thing: it’s an astonishing coincidence that the Wallace family could have killed Elliot’s wife, and that Elliot, five years later, through completely independent mechanisms, could have ingratiated himself into the Wallace organisation as an undercover detective. For a second thing: that spectacular coincidence graduates to a straight-up plothole, in view of the fact that the Wallaces surely must have been aware of Elliot’s existence prior to the events of S1 E1. If they had enough intelligence on Naomi Keegan to assassinate her, they surely must have been aware of her husband and the father of her child, to the extent that they’d recognise him when he showed up in their organisation under the half-assed alias of “Elliot Finch”?

Season 3 treats the events of Seasons 1 and 2 as a kind of rough sketch. It cherry-picks the details that suit it, and discards those that don’t. It’s disorienting and unpleasant for anyone who’s actually paying attention, and a show that lasts as long as three seasons tends to do so because it has viewers who pay attention.

Season 3 treats the events of Seasons 1 and 2 as a kind of rough sketch. It cherry-picks the details that suit it…

But, anyway: I was talking about how this season works as a self-contained tragedy, even if it emphatically doesn’t work as a continuation of what came before. Billy is cut up about what his family did to Elliot; he’s done the moral arithmetic in his mind, and he recognises that the loss of his left arm is small potatoes compared to the murder of a wife and child.

Amongst Gangs of London’s cast, Billy has always been the most cursed with self-awareness; exquisitely sensitive to the ways that his actions impact other people. It’s because of that sensitivity that he’s content to be drawn into other people’s causes; whether it’s his father, or his mother, or Sean, or Cornelius, he’s able to feel just a little less guilty and miserable if he’s hitched his wagon to someone else’s crusade.

For as violent and aggressive as he can get, particularly in this season, Billy always occurs as a stunted, scared boy. One particularly apt flashback in this episode is to the moment when he shot the bucket in S1 E2, killing the man cuckolding Finn so that Sean didn’t have to. That’s been Billy’s role his whole life: a sin-eater, taking his family’s iniquities upon himself to insulate them from their guilt. In his confrontation with Marian, Billy questions her in ways he’s never questioned any of his family before: when does it end? How many more lives, before he can be happy?

Marian, of course, doesn’t have a satisfactory answer. There is no number of lives.

Elliot is kind of Billy’s antithesis, in this regard. Elliot doesn’t march to the beat of anyone else’s drum. He’s fiercely, defiantly independent; relentlessly goal-oriented. Whether working to take down the Wallace organisation in Season 1, or getting his revenge on Sean in Season 2, or tracking down his family’s killer in Season 3, he’s always defined his own values and priorities, and pursued them single-mindedly.

Correspondingly, what he lacks is self-awareness. Elliot is focused on his objectives with such tunnel-vision that he blinds himself to the harm he leaves in his wake. It’s in Season 3’s denouement, rocked by Vaughn’s revelations, that he’s finally compelled to reflect upon his own actions, and reckon with the fact that he participated in exactly the system that got his wife killed, simply so that he might spite Sean. He turns Naomi’s files making the case for legalisation over to Simone, and tells her to keep following her conscience. Henry might have been corrupt, but she isn’t, and her push for drug reform comes from a legitimately noble impulse, even if Vaughn attempted to co-opt and corrupt it. For once, Elliot’s been given cause to step outside of himself, and it feels like a moment of authentic, personal growth.

For a hot moment, it looks like Season 3 will end on a positive beat. There are notes of sweet added to all the bitter with the resolution of Luan’s subplot; he takes Shannon and Danny hostage, preparing to execute them in reprisal for Elira’s death, as proxies for Ed. Mirlinda’s rebukes don’t dissuade him, but when he’s confronted by Shannon, pleading and crying and shielding Danny with her own body, he can’t bring himself to do it. (The moment wouldn’t be complete, of course, without Orli Shuka’s tormented, vein-popping reaction shots. Please never change, you great, big, Albanian ham.) We’re given cause to hope: maybe the cycle of reprisals really can end.

But then it all comes crashing down. While Simone is delivering her address declaring war on the criminal gangs, Billy invites Elliot to a rendezvous in an out-of-the-way warehouse. Billy spends the time waiting for Elliot to arrive drinking copiously from a bottle of tequila, interspersed with bumps of coke.

When Elliot arrives, he sits down opposite Billy at a steel table. Billy’s promised him information on who really killed his family, but seems oddly reticent to give it up. He keeps taking sips from his tin cup, with an increasingly shaky right hand.

“Look at my Dad.”

*Sip*

“Look at Sean. Look at the Dumanis. Even Luan’s family. All of them, fucked. Nobody wins. Nobody ever fucking wins.”

Billy places a loaded handgun on the table, and slides it across to Elliot. He confesses his complicity in the murder of his wife and child, and he begs Elliot to kill him.

As story themes go, “crime doesn’t pay” is one of the tritest and most basic and most reducible. But it’s a theme that acquires a certain elemental potency in this confrontation between two sympathetic characters. Ultimately, Billy isn’t able to escape his past sins; nor is Elliot able to divest himself of the need for revenge. The final shot of Season 3 is an exterior crane shot of the warehouse, where we hear two gunshots, punctuated by two muzzle flashes. The camera rises indifferently to view a sunrise over the London skyline, unchanged by all this tragedy. A title card intersects the horizon, and we cut to credits.

If this was the last episode that Gangs of London ever broadcast – if there was never another episode after this one – I would have a lot of respect for this as an ending. For the full-throated bleakness and futility of it; the insistence that all of these characters are fundamentally damned.

Of course, the thing about a tragedy is that it requires an ending as a fulcrum point. And I don’t think that Pulse Films are remotely ready to let Gangs of London end, for as long as they can feasibly keep it going. And I don’t remotely believe that Billy is dead: after a season full of major, named characters shown erupting with exit wounds, and Zeek still at large, this allusive exterior shot is far too obviously the showrunners leaving the door open for a Season 4.

Of course, the thing about a tragedy is that it requires an ending as a fulcrum point.

(For what it’s worth, in the process of researching this season I stumbled across Executive Producer Vikki Tennant’s Linkedin profile, where she registers her job title as “Executive Producer – Gangs of London S3 & S4.” So, it definitely seems like the creative staff have a fourth season in mind.)

Is It Good?

Nearly Good (4/8)

Season 3 overall

Is It Good?

Nearly Good (4/8)

More Gangs of London reviews

Andrew is a 2012 graduate of the University of Dundee, with an MA in English and Politics. He spent a lot of time at Uni watching decadently nerdy movies with his pals, and decided that would be his identity moving forward. He awards an extra point on The Goods ranking scale to any film featuring robots or martial arts. He also dabbles in writing fiction, which is assuredly lousy with robots and martial arts.

4 replies on “Gangs of London, Season 3, Episode 8”

Some seriously laugh aloud moments in this review. I especially liked ‘so I guess this congress of ultra-rich criminals operates on an RSVP basis, like your cousin Vera’s wedding.)’ And ‘Please never change, you great, big, Albanian’. Brilliant.

I deeply respect your analysis – moving from cinematic techniques (S1) to meta & sociological themes (S2). It’s been an absolute highlight to watch the show & read your reviews.

We’ll never agree on the episode with Lale in this season – but one episode out of three seasons is OK by me. I thought that one was the best of the season. But, yeh, it was flat in its style.

I’ll genuinely miss these reviews.

That’s really sweet of you to say, Jo, thanks! Great to know that this series helped to enrich the show for you!

FWIW, I definitely intend to continue these, if and when Season 4 drops (and as long as Dan is happy for me to keep dropping >2,500 word articles in his inbox on a Tuesday afternoon, lol.)

Genuinely surprised that last minute “twist” fooled you. When I first watched ep 1 “I was like, oh that’s Billy then right?” Could clearly tell by his unmistakable gait.

So I was surprised when they played it off in the finale as some sort of a shocking twist.

Was a decent finale. Surprised Lale wasn’t in the last one either IIRC. Just wish we could get back to the highs and thrills of S1 eps 1-5. That was incredible.

Need Gareth Evans back pronto. His style and talent is clearly unmatched.

Fair enough – you’re definitely more keyed-in to how Brian Vernel walks than me, lol!

I’d love to have Evans back, but I don’t know how likely that is. Last I heard, he’s developing a remake of a 60’s Yakuza flick for Amazon.