With the most

Imagine my surprise when I watched this Korean monster film from 2006 and discovered that it is, in fact, a film about COVID. Is Bong Joon Ho a time traveler?

Of course, The Host is sufficiently sophisticated and broad as a piece of storytelling that its themes can mirror an entire spectrum of topics, but it really is shocking how incisive the film is about life in 2020 and 2021, and through today to some extent. Bong was prescient about the psychological deterioration of quarantine, the bureaucratic mess of a broken public health system, and the lingering hangover of government policy that fails its people that we witnessed during COVID (and to this day). Underneath the catastrophe is the capitalist rot at the root of it all: the disaster of a society that cannot support its citizens, especially its most vulnerable and broken families, like the one that The Host is centrally about.

This is Bong’s third film, following the bizarre Barking Dogs Never Bite and the brutal Memories of Murder. It marks a milestone in his career for a few reasons: It’s his first foray into science fiction, his first real swing at eco-horror, and the most elaborate production he’d attempted up to that point. Unlike his first two films grounded in reality, The Host is a full-on monster movie, and a damn good one. It takes cues from the big kids of the genre, especially the original Godzilla, in that the monster is rarely the central subject. Rather, the story is about the people scrambling in its wake with a dangerous giant reptile as backdrop. But unlike Godzilla, where the human focus is on scientists and military personnel, Bong shifts the spotlight onto a semi-functional lower-middle-class family.

(As an aside… I know it’s the conventional wisdom and critical consensus at this point, but I just want to remind everyone that the original Toho Godzilla from 1954 is an outstanding and deeply felt film, as opposed to the butchered and dubbed B-movie with added Raymond Burr footage released in 1956 that was received in the US as campy junk. Watch the subtitled original if you haven’t. It’s worth it.)

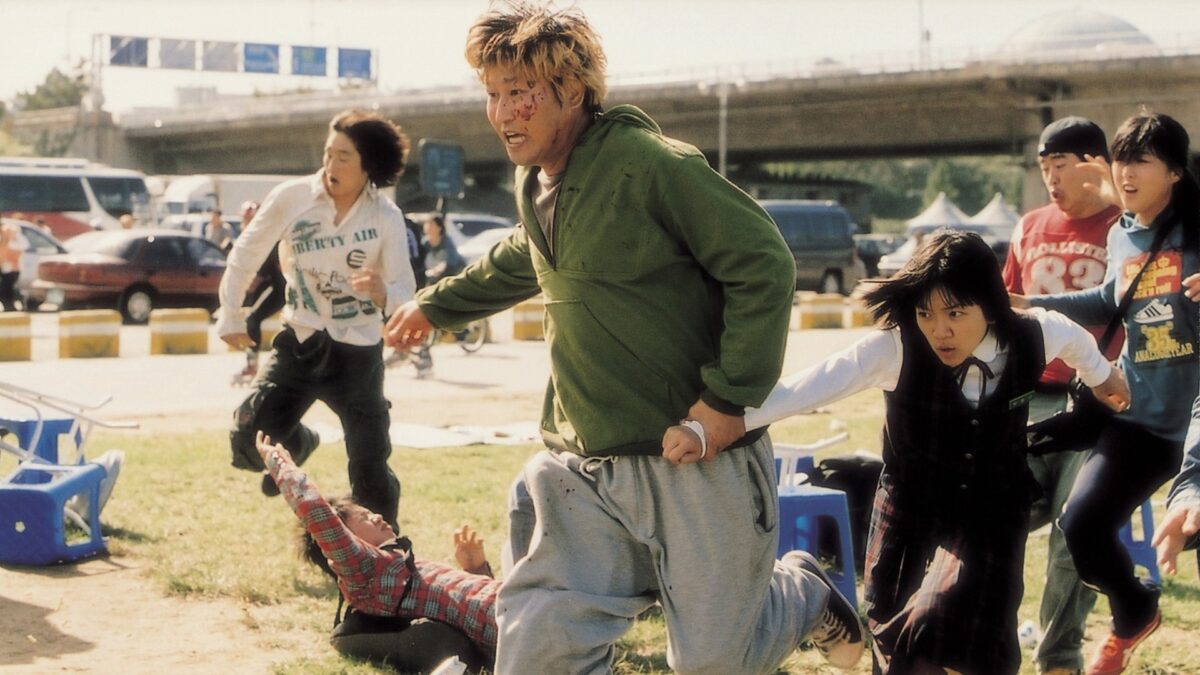

The first half of The Host is really terrific — a taut, darkly funny setup that quickly escalates from slice-of-life family dysfunction to riverbank monster mayhem to full-blown international incident. Following a chemical dump into the Han River, a mysterious creature emerges from the water and goes on a rampage. Park Gang-du (Song Kang-ho), a slow-witted snack stand worker with frosted tips, watches in horror as the monster scoops up his daughter Hyun-seo (Go Ah-sung), and he presumes her dead. His family gathers in grief and shock, only for men in white hazmat suits to corral them into a quarantine facility and announce that they may be infected by “the virus.” When Gang-du receives a garbled phone call suggesting Hyun-seo is still alive somewhere in the monster’s sewer lair, the family stages a jailbreak and sets off on their own rescue mission.

The monster itself is a thing of wiggly, slimy beauty. Designed by The Orphanage visual effects team, it’s part overgrown tadpole, part hairless squirrel, part clump of hair caught in your shower drain. It gallops and swings by its tail, and it vomits bones, bodies, and trash into sewer grates like it’s building a nest. Its maw resembles female genitalia, adding an extra layer of black comedy and bizarre imagery when it spits out human bodies like a mutilated birth. Its first appearance is breathless velocity, serving as a contrast to the misty horizon introduction to Godzilla we got in 1954. No teasing, just sudden chaos tearing across a park as people scatter. The CGI isn’t perfect, but holds up better than plenty of other effects-driven films of the era.

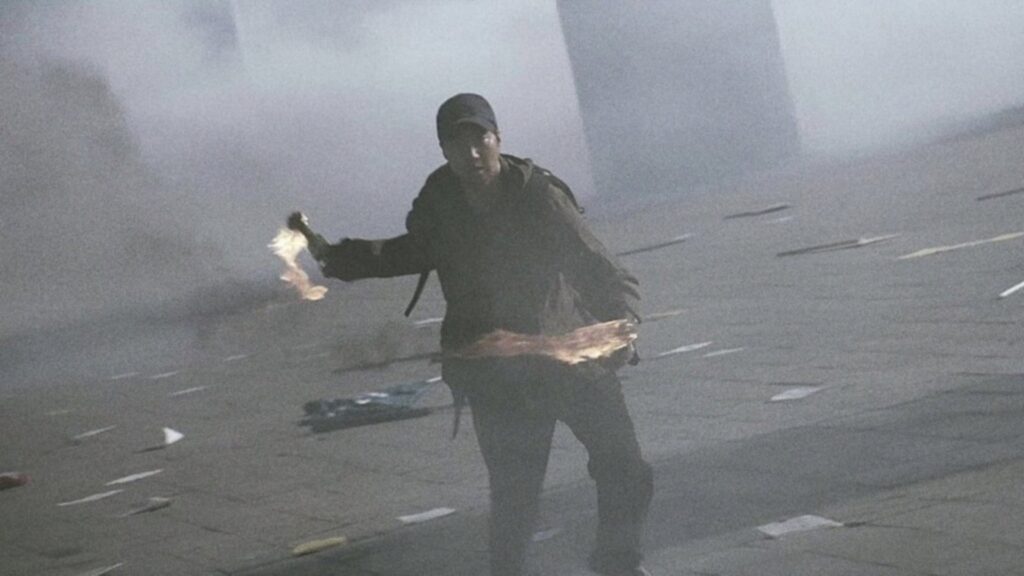

The Host’s creature feature action scenes are fast-paced and well-staged by Bong. He’s constantly inventing new scenarios for the creature, culminating with a battle with a flamethrower. And it’s certainly a film you can enjoy on a surface level. But where The Host really shines is its deeply cynical commentary about institutional failure plaguing Korea (an ill that was perhaps contracted from United States, Bong suggests). When the monster snatches Hyun-seo, it’s not just a kidnapping — it’s a metaphor for what happens when the next generation pays for the mistakes of the last. The film begins with an American military official demanding that toxic chemicals be dumped into the Han River, triggering the monster’s mutation: Thus the film is a portrait of environmental negligence and foreign interference. In the film’s middle act, Bong paints a bleak but all-too-familiar picture of authorities handling a contamination crisis with more interest in political optics than human-based outcomes.

That said, the film’s second half doesn’t hit quite as hard as the first. Once the family splits up following the escape of the government facility, some of the emotional charge and cast chemistry dissipates. Each member ends up in their own subplot, some more compelling than others, and the scattered energy makes it harder to stay locked in. The ending is surprisingly bleak. Without spoiling specifics, it involves an unexpected death that shocked me on first watch. It’s not entirely unjustified — it fits Bong’s grim worldview and penchant for unsatisfying finales — but it definitely sucks the wind out of the film’s conclusion. I suppose Memories of Murder had the same jarring disappointment in its inconclusive ending.

What I most love about The Host is its big picture implications for Bong: how savvy and brave a pivot it was for the director. Coming off the festival acclaim of Memories of Murder, he could’ve gone all-in on prestige drama. Instead, he made a monster movie, a genre often dismissed as juvenile or passé, and infused it with all his strengths as a filmmaker: allegory, slapstick, and daring tonal shifts. It’s a wild stew of flavors, and yet it’s recognizably Bong. His visual style here is very mature and effective: the quick camera tilts, the boxy facial close-ups, the disorienting fog in the climax, the claustrophobia, etc., all operating at a high level and mirroring techniques he’d already developed. The film has a couple of Bong’s signature tonal U-turns that give the audience whiplash and inspire debate. Just as Memories of Murder and Barking Dogs Never Bite found personality in the day-to-day living details of its characters, Bong doesn’t lose sight of the minutia in his monster-plagued settings here: He calls attention to a recurring bowl of noodles, a cheap hair dye job, a bad parking job announced over the loudspeaker during a time of grief, etc.

The Host, following Memories of Murder, established a pattern in Bong’s filmography: alternating between dark dramas (Mother, Parasite) and monster movies (Okja, Mickey 17), both flavors vessels for charged social commentary. That pattern continues with only a single variation (Snowpiercer) all the way through today. According to Letterboxd and IMDb statistics, The Host isn’t watched as often these days as many of Bong’s subsequent films, but it’s foundational work for the director, declaring his enthusiasm for speculative fiction and reinventing the monster horror film in the mid-2000s. Though if you told me today that he actually made it in late 2020 and smuggled it back to 2006, I’d only ask where the time machine is parked.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.