Some terrific, radiant, humble thingamajingamapig

Seasons change. People act for their own benefit. The world is filled with violence and injustice, some of which we can reduce, but much of it we can’t. Loved ones die and depart, leaving us lonely and confused. But their lives and impacts still have meaning, and it’s our obligation as a decent humans to take the love they inspired in us and spread it out further into this world.

These are all fundamental truths of life, accepted in some form by all nationalities, religions, and creeds. Many great works of art try to convey these concepts. Sometimes even for children. But rarely does a story tackle these themes so directly and tenderly as in Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White.

As a kid, I read Charlotte’s Web, and it left an immeasurable impact on me. White’s book is a masterpiece, understated and deeply humane. It is a fable, but its confrontation of death and grief is unflinching without descending to misery. This past month, I read the novel aloud to my five-year-old and three year-old. It gave us an opportunity to talk about the sadness of losing someone we love, but also how their kindness can still grow inside us after they pass through our lives. I hope that the experience will make it just a little bit easier for them to process loss when it inevitably hits their own lives. I like to think the story did so for me.

That makes it sound heavy, but Charlotte’s Web is funny and occasionally wacky. It’s these even when it’s challenging. The lightweight charm of its story and characters, the sense of wonder it evokes, might even surpass its ability to grapple with big topics.

As we read, I promised my daughters that we would watch the adaptation once we finished. I had watched the Hanna-Barbera adaptation as a kid, and elements of it really stuck with me. (In 2006, Paramount released a live-action adaptation, but I decided to show my kids the one that I grew up watching.) I hadn’t seen this film since I was maybe nine years old, and watching it with my daughters brought back memories and sensations that had been locked deep in the dungeons of my long term memory. (Good memories, I should clarify.) I remembered these songs and voices and moments, even though I thought I’d forgotten them.

This cartoon adaptation is created by the animation studio Hanna-Barbera. It was founded by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera (the creators of MGM’s Tom and Jerry shorts) to create animated TV shows once the TV market started to grow in the ‘50s. Hanna-Barbera are best known for churning out animated sitcoms that grew in fame when they were syndicated on daytime TV for many decades after their original release. You might have watched some of their shows yourself (I did): The Flintstones was their most iconic property, but they’re also responsible for Scooby-Doo, The Jetsons, Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, and plenty of others that you are probably familiar with.

Charlotte’s Web was Hanna-Barbera’s first stab at a feature-length theatrical film (excluding extensions of their shows). They landed the rights for the book and then recruited the legendary Sherman Brothers to write accompanying numbers.

This is an honest and faithful adaptation of Charlotte’s Web, which puts a high floor on the film’s potential quality. This was unlikely to ever be a bad movie. The story in the book is just too good for an adaptation to fail. And thankfully, Hanna-Barbera does not approach that floor, although the film does have a few quirks and blemishes

The most striking element of the production is the soundtrack. The Sherman Brothers deliver a score very characteristic of their style, filled with marches and waltzes and patter numbers. These tunes often feel a bit askew with the dry tone that Charlotte‘s Web otherwise has. It’s quite jarring when the farm animals abruptly break out into cheerful song. I suspect part of the problem is that the story was not conceived of as a musical, and thus there’s a little natural build up or transition to the numbers.

But the Sherman Brothers are great songwriters, and many of the songs here are terrific. The upbeat numbers are all earworms, almost unnaturally catchy. “Zuckerman’s Famous Pig,” the triumphal barbershop quartet anthem, has been running in my head on loop since I watched a few days ago.

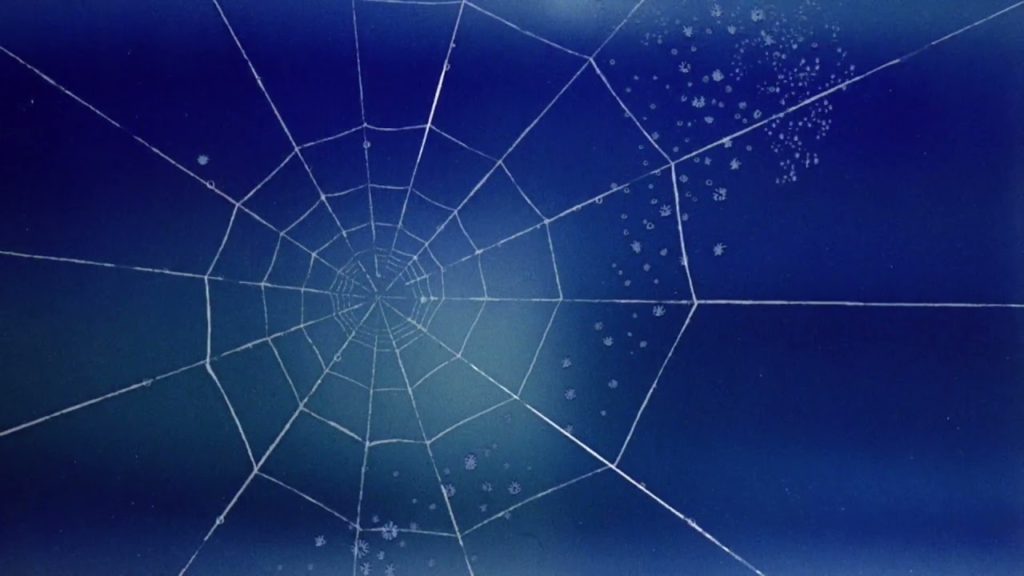

My favorite songs are the bittersweet ones, though. Two particularly great minor-key numbers are accompanied by abstract and evocative pieces of animation, more ambitious than any other segments in the film. These two songs, the waltz “Deep in the Dark” and the folk-style ballad “Mother Earth and Father Time,” fit and develop the story’s themes very well. There’s a particular melodic line in the chorus of “Mother Earth and Father Time” sung by Charlotte (Debbie Reynolds) that is heart-rending and perfect.

For some people, the soundtrack is a deal-breaker. In fact, author E.B. White thought the songs distracted too much from the story. And while I wonder what a quieter, more meditative version of this film might have looked like, I’m still glad for the busy score. The numbers add quite a bit of energy and color, and are generally just great ditties.

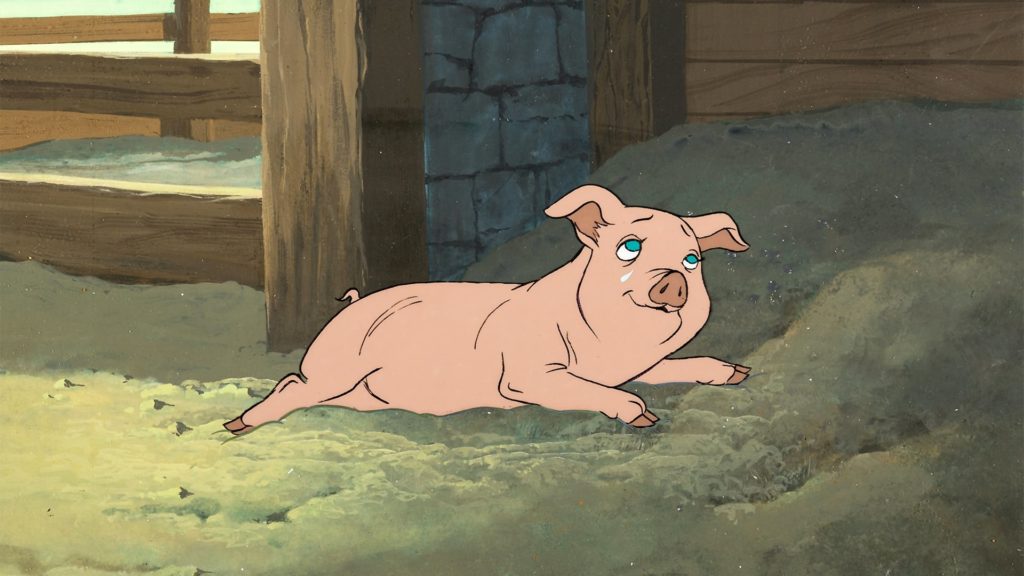

Less defensible is the animation itself. Some parts of it are great: Charlotte is terrifically designed and animated, evoking ethereal danger and graceful beauty in equal measure. But some scenes are downright choppy and ugly. (There’s an effect of Fern sledding during winter that is little more than an unchanging cel dragged across a simple background, and I audibly groaned at its tackiness.) The animals fare better than the humans, which look Xeroxed from the same four character templates, but the proportions and coloring of the creatures are wildly inconsistent (just look at the various screencaps of Wilbur included in this review to see how much his pink shade varies).

The voice acting is led by Reynolds, who captures Charlotte perfectly. I’m a bit mixed on Henry Gibson as the voice of Wilbur the pig: I can’t figure out why they didn’t cast a child actor who could have brought more wide-eyed innocence than Gibson’s sweetly affected voice. Gibson at least brings expressive range to the character, capturing both grief and whimsy; it just never sounds like a discovery.

The side characters all have solid voice acting, but a special shoutout goes to Hanna-Barbera regular Paul Lynde, whose flamboyant Templeton the rat is a frequent scene-stealer.

It’s not as lush a production as anything Disney released to theaters, even during this relatively quiet era. But there’s real heart here, both in the narrative and in certain aspects of the production. And with a source story so moving and foundational, it’s impossible not to love.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.