Mic dropkick

Rape and murder are not funny. But Memories of Murder is a funny movie without ever undercutting the gravity of the crimes its protagonists are investigating. This is one of the tensions of Bong Joon Ho’s second film, his critical breakout. Cho Yong-koo (Kim Roi-ha), a local cop who previously has had to deal only with petty burglaries and drunken thugs, believes every illegal act can be solved by dropkicking a suspect. It is always funny to see Cho come running in frame, then launching himself in the air at a potential criminal. Later in the film, Cho’s reckless use of violence comes to the forefront, and he’s suspended from the force for brutality. He grows despondent and alcoholic, and gets stabbed in a bar fight with a rusty nail. His dropkicks against innocent victims are not so funny now. Except they still are. It’s terrific slapstick, and it’s capricious violence. It’s both; a tension.

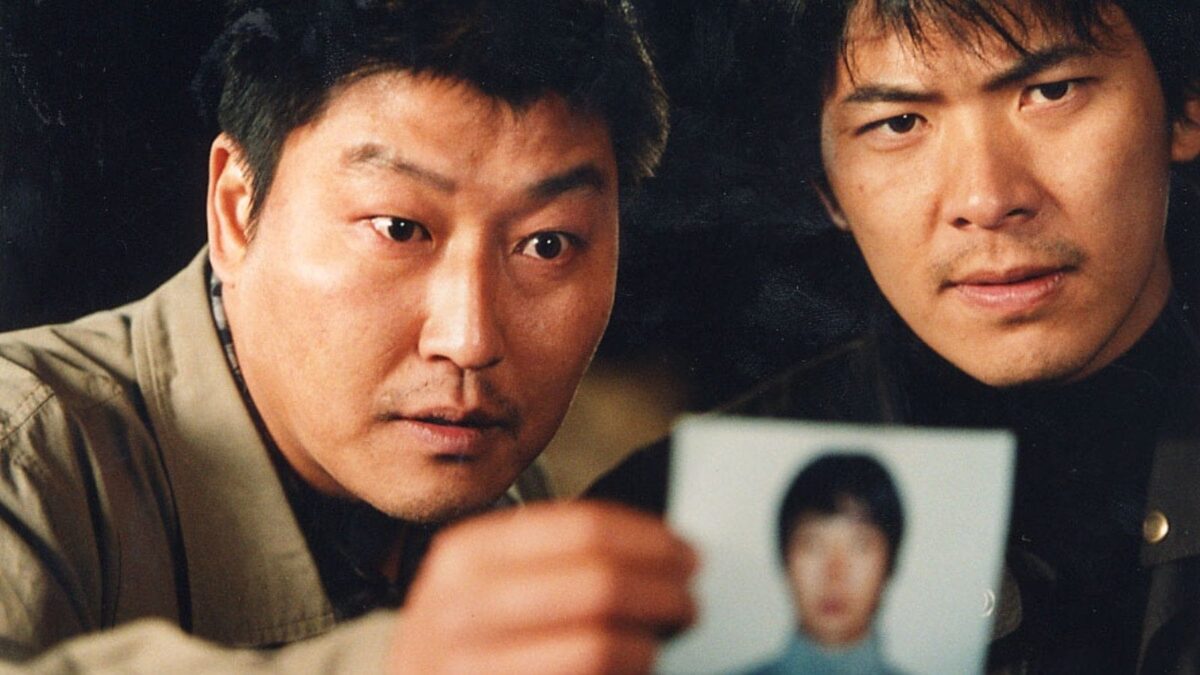

This is not the only one of Memories of Murder’s tensions. The film, which is set in an outskirt town of Seoul that is unnamed but inspired by Hwaesong, also considers the push and pull between intuitive perception and measurable facts. The film’s two leads are rural detective Park Doo-man (Song Kang-ho, a frequent Bong collaborator), who knows the town and its people well, and big-city Seoul investigator Seo Tae-yoon, (Kim Sang-kyung) who is trained in evidence-based forensic techniques. They repeatedly butt heads during the investigation: one trusting his eyes and gut, the other trusting patterns of evidence. A narratively satisfying approach to this pairing would be a pendulum swing where each investigator is right sometimes and wrong sometimes, their approaches ultimately marrying in a conclusive finale wherein the detectives apprehend the villain and justice is served. But Memories of Murder is not designed with this conventional rhythm. Instead, the intuitive Park is wrong over and over, or at least incomplete in his conclusions, while Seo finds truth in the precision of details. Yet just when this theme has locked into place, of big-city procedure trumping small-town instinct, the finale rips it from the investigators’ hands. Bong ends the film without closure or proof of guilt. He asks the viewers to reconsider what he just laid out: that we should trust the facts rather than our sense of narrative instincts. The presumed culprit walks away because the detectives can’t find proof of his wrongdoing; we just know he’s guilty. Maybe Park was right in the first place even though he was wrong every step of the way. Maybe truth is something that you see in a person’s eyes even when evidence can’t definitively back it up.

Like most great crime stories, Memories of Murder is not just a procedural unfolding of a case, but an investigation into the human soul and its various shades of darkness. For Bong Joon Ho, observing humanity’s violent impulses is synonymous with reckoning with the systems that shape us. As a university student and young adult, Bong was a protester against the oppressive, anti-progress Korean government during the late ‘80s when this is set. About two-thirds into the runtime of Memories of Murder, Park and Seo find a traumatized woman who survived a violent attack, and she flees from them. As viewers, we do not blame her: She was brutalized by a cruel man, and then by an institution that did not notice or care that she had suffered. (The detectives are both men and the broken system at once!) The only recognition the woman received was to become a local ghost story told by schoolkids; her trauma a frivolity. This is where Memories of Murder feels just as apt to the USA in 2025 as to South Korea in the ’80s: As a nation’s leadership and policy regresses, so do its communities, and so does the welfare of its most vulnerable people. That’s not the text of Memories of Murder, but it’s barely under the surface.

The film, based on a string of real-life, headline-grabbing murders near Seoul, opens with a scene that captures its tonal juggling in a nutshell: Park and Cho arrive at a crime scene of harrowing ugliness: a dead woman, the killer’s first victim, is bound and gagged with her undergarments, stuffed in a coffin-shaped drain pipe, and covered with insects crawling all over her flesh. The local cops are equal parts stunned at the cruelty of the scene and miffed at the commotion interfering with their job: locals show up, mostly unfazed and curious about the spectacle, disrupting evidence. It’s a well-orchestrated comic scene that would be a wacky Keystone Cops routine if not for the mutilated corpse at its center.

The detectives bungle the early portions of the investigation to a point that it would again be hilarious if not for the stakes. Park and Cho round up the usual suspects and canvas for leads. They hear a rumor that a man with cognitive problems, Baek Kwang-ho (Park No-shik), had a history of pestering one victim. They arrest him and smack him around until he confesses under duress. Admitting he did it is the only way they’ll leave him alone. The cops toss him in jail. Everyone declares the case solved, until Seoul hotshot Seo pokes his head in, spends about 10 seconds reviewing the facts of the cases, and determines Baek is not the culprit. From there, Seo and Park make uneasy partners, each eventually learning to reign in the other’s worst habits as the case spirals to its resolution. We slowly gather that Park is a local cop not because he’s passionate about serving justice, but because it was a career path that lay in front of him. He took the job the way one might become a plumber or an office worker. Seo, meanwhile, has bound his identity in cracking cases, his hardboiled neuroses festering as the case drags on.

Every beat of the investigation, right until the last 20 minutes, seems pretty conventional on paper. And to some extent, each one is conventional. But it never feels quite right. It unfolds arrhythmically and in spurts, as if the movie is as baffled at the unlikelihood and cruelty of the serial rapes and murders as the residents of the small town are. Sitcom and farce beats are interrupted by new murders, and vice versa. Rain becomes a harbinger of doom as Seo figures out that the killer only attacks during bad weather.

The film’s closing stretch is its strongest and bleakest, and it bumps the film up a tier. Every bit of levity the film has offered to this point curdles into an abyss of dread and failure, captured in a stirring shot of train track tunnel. The tunnel is a mouth of darkness, swallowing everything good and innocent outside it, portending doom and destruction that might strike like a freight train.

Is history a spoiler? I don’t know. You might want to stop reading if you don’t know the full story for this string of real-life 1980s murders in Hwaesong and are spoiler-averse. But I will proceed on the assumption that you are familiar with the broad outlines of the case and, therefore, the conclusion of Memories of Murder.

This film debuted in 2003, and Bong based it off of a 1996 play dramatizing a real investigation into a serial killer. As of the release of the play and the film, these murders were unsolved. The serial killer ran free. Finally, in 2019, police arrested a man named Lee Choon-jae for the crimes from three decades earlier. He confessed and will spend the rest of his life in prison. But this arrest occurred well after Bong’s movie premiered. (In fact, many authorities and media outlets credit the film for keeping interest in the case alive.) Thus, Memories of Murder ends with the case unsolved. A flash-forward coda shows how life goes on even as evil persists. The abyss remains. Park remembers the high stakes investigation as part nostalgia, part nightmare. The final shot is one that might be a gimmick in a lesser film, but here punctuates many of the film’s complex ideas: Evil doesn’t lie in one man’s soul but in a broken community. The system has failed us. Yet, we’ve also failed the system by allowing it to endure. Why do some people get to live happy lives while others lie as corpses in the gutter? We get no firm answer this question, but Bong presents it as a challenge more than a moan of despair. He dares us to figure out who we can hold accountable (and how) for a culture that accepts inequality and violence, even if accountability means looking in the mirror.

Bong’s filmmaking is tremendous all throughout Memories of Murder. He has taken the spinning plates balancing act of distinct tones from Barking Dogs Never Bite and exploded it into the raison d’être of a crime story. The bursts of darkness and comedy are alternating and concussive. Most impressive are the blocking and construction of interior scenes in the police station and buildings around town: they are claustrophobic and precisely designed, foreshadowing his world-class interior set pieces in Parasite.

The leap from Bong’s first film to his second is remarkable. Memories of Murder is a legitimately great film. It is often frustrating and repetitive: Park is so haphazard as a cop, he’s unlikable, and the whole department’s series of blunders is exhausting. But in the moments when the film is unsatisfying, it’s always in a provocative way, a reminder of the clash between two cops stumbling to solve a mystery out of their league and to confront the gaping darkness they uncover but cannot extinguish.

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.