It's like poetry, they rhyme

This movie is unreviewable. I’m not sure there exists a film with more baggage and context in the medium’s history. It is an inflection point in the form and creation of blockbuster films, for the first time more CGI than human, humanity and artificiality living in an uncanny shared reality. It is the birth of the concept of a “cinematic universe,” the intellectual property model that would increasingly come to define Hollywood big-budget filmmaking. In this mode, a franchise is not merely a series of films, but a collection of interlocking series, the potential fractals of merchandising and storytelling spinning out into infinity. Every licensable surface and material marketed The Phantom Menace to the (that’s-no-)moon and back.

The influence and long cultural tail of The Phantom Menace do not stop there. There’s a weird bubble and reputational arc surrounding the Star Wars prequels. Baffled critics gave it lukewarm contemporary reviews tilted towards the positive, but it received the motherlode of all backlashes from fans who found its stilted script, dull storyline, and disastrous comic relief the very anathema of Star Wars’ epic space charm. George Lucas, one of the most influential filmmakers of all time, finally returned to the director’s chair and became geek villain number one, a crazy old coot who was sullying his legacy with Gungans and midi-chlorians.

Inevitably, something else has happened, too. In the wake of increasingly cheap and crappy blockbusters dropped to cinemas, both in the Star Wars brand and otherwise, the 10-year-olds who watched it starry-eyed on first release have reclaimed The Phantom Menace with a nostalgia-colored legacy as a pure piece of spectacle that maintained a real author’s voice and a loopy charm. The Star Wars prequels have gone through a post-ironic memeification that tops even Shrek, which seem to have convinced Gen Z and younger millennials that these films are worthy institutions, foundational films.

The result is a movie — nay, a cultural product of any sort — that is still one of the most famous on the planet. I mean, you already knew everything I wrote in the previous couple of paragraphs, right? If you are at least 35 years old and grew up in middle- or upper-class America, you saw this in theaters, correct?

So let me take a step back. Let me try to do the impossible and shed not just the cultural paratext of the film but my own: After all, Star Wars was my favorite of the speculative fiction franchises when I was a kid, and, thanks mostly to John Williams, it still probably is. As a tween, I read guidebooks on the different kinds of ships and swapped facts with my buddies and read a couple of Extended Universe novels. I was indeed one of the kids who stumbled into an over-air conditioned theater to see The Phantom Menace not just hoping for greatness, but presuming it. I can’t tell you what my reaction as an eleven-year-old was, but I certainly grew sour over time. By the release of Episode III when I had entered my late teen years, I was a full-on prequels skeptic.

Prior to this past month, I haven’t watched any of the prequels since 2015, just before Episode 7, and even that viewing hardly counts: I found a 2.5-hour fan-edited cut of all three prequels combined into one. And the last time I watched any of the prequels in their entirety… damn, college? Maybe my early 20s? I’ve watched a lot of movies since then, which includes a lot of Star Wars: the sequel trilogy (just once each) and the original trilogy (about four times each) and Rogue One. But I’ve steered clear of the prequels.

But the time has come. I hit play and tried to clear my head of biases, one who knows Star Wars but isn’t a superdork about it. Immediately, I failed. Within minutes, I was thinking about how this falls into my schema of the franchise. What’s tough about answering the question “Does Episode I feel like Star Wars?” is that each of the three movies in Luke’s trilogy operates in very different registers. The original masterpiece is pulpy and light on world details, instead offering an overwhelming feeling of a crushing space empire, a gritty rebellion, and a plucky trio stumbling to victory. Empire Strikes Back, a (slightly lesser) masterpiece in its own right, fills in the gaps and expands the world, showing a crumbling moral resistance in a bleak and gray world, mostly to glorious effect. And the very uneven Return of the Jedi spotlights a boardroom-designed menagerie of merch-ready aliens and costumes grafted onto a soul struggle of good and evil, of sin and redemption, between father and son and black-robed Satan.

But The Phantom Menace is a brand new fourth thing: Boring. It’s a clumsily executed political story of an engineered economic crisis. Lucas neuters the adventure flavor every chance he gets, especially the sense of mysticism and destiny: The Force is reduced to a blood-organism, the Jedi into a bickering government council. Gone is the thrilling promise of space magic. (I can imagine a world where this subversion is fascinating and intellectually challenging, but this is not that world.) There is no proxy teen hero to gawk in wonder at the spectacle-filled galaxy at the same time as the audience. I’m not counting the new chosen one, the aw-shucks Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd) whose overwhelming wholesomeness exists entirely for dramatic irony, as we know he will become Darth Vader one day.

The film’s story problems are legion, but you can start with the protagonist, Qui-Gon Jinn. The film has no idea what this character is, and neither do I. He is acted by Neeson and spoken about by other characters as a wise and stoic paragon of humble virtue. And then you listen to actual things that he says and you witness the actions that he takes, and you get the exact opposite impression. Rewatching for the first time in so long, I was taken aback by how much of the movie is Jinn making wild assumptions and taking crazy risks. He gets by on the skin of his teeth and good luck over and over again like he’s a classic prankster spirit rather than a sage monk. Narratively, he should be the intrepid hero; and he has a sliver of that. So does young Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan MacGregor) and royal handmaiden Padme (Natalie Portman), though not nearly enough.

The narrative conflict is so convoluted and aimless it borders on a shaggy dog joke. Our launching point is everyone’s favorite space opera topic: trading regulations. The script is a nonsense generation machine that bounces erratically between concepts that barely have any connective tissue to pull it all together. The inciting incident is an assassination attempt, which pivots into a submarine chase, then a gambling thriller, then a racing showdown, then a space age Tolkien monsters-vs.-robots battle, then an epic swashbuckler, and finally a heist story.

I’ll admit the genre combo I just described actually makes The Phantom Menace sound cool as hell, a gumbo of epic genres given a galactic facelift. And if that had indeed been the pitch and execution of Star Wars Episode I — a loving tribute and modernization of out-of-style tentpole genres for 15 minutes at a time — the film could have been great. But the film rarely ever hits that potential. I suspect this was Lucas’s grand vision, but he didn’t do much to get it on the page or on the screen. Nearly every scene is dull and perfunctory; never pulpy or sweeping. The pieces never cohere into an arc. Every scene presents some story idea and treats it with fastidiousness as if it’s a crucial plot point we will be invested in. But we never are because it only barely makes sense or fits into anything bigger. The film’s moments are all little, baffling snippets that immediately make you forget how each character got there and what their motivations are. It’s basically impossible to care about what’s going on.

Some parts of the story are just so stupid. There’s a late twist that the queen of Naboo, so central in the political machinations that drive the story, is in fact a decoy, and her handmaiden Padme is the real queen. But then why did we just spend most of the movie watching the decoy queen going through negotiations and giving orders? If the whole conceit of the fake queen is to protect the real handmaiden queen, why does the real queen barge into the dangerous, crime-infested desert slum with Qui-Gon? And when there are real tough decisions to be made on the fly, does the decoy queen make them herself? It sure seems that way. It makes no sense, and it’s just one such example of a logic-defying story point.

There should be some delicious irony in rooting for the Republic we know will be the evil Empire, of cheering for a queen who will trigger the downfall of a generation. But it’s all so lifeless. It’s mired in some bizarre politics, too, that might actually bother me if the film was competent enough for any of it to register: The film expects us to cheer when the indigenous Gungans volunteer to fight the humans’ war in exchange for being acknowledged as sentient creatures worthy of rights. The characters all haphazardly take slavery as a face-value fact of the universe.

The dialogue is the worst of it all, which is saying something. Maybe Darth Maul had it right staying nearly silent the whole time. (I like the idea that he’s taken a vow of silence as an evil monk, but he speaks once or twice, so I guess he’s just shy.) The Phantom Menace makes the original Star Wars‘ clumsy script seem like Shakespeare; here, characters state their themes out loud with a cadence and eloquence that reads like a high school freshman’s first draft. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan have conversations that sound like poorly translated Sun Tzu nuggets. Exposition is hilariously duct-taped on: “Ah, you mean the prophecy, never previously mentioned and never to be mentioned again? The one about a force user who will bring balance to good and evil, though currently good Jedi are in control and we believe the Sith to be exterminated, so a change ‘balance’ would definitionally tilt the balance of power towards evil? Is that prophecy of which you speak?” I’m only barely paraphrasing a quote from Samuel L. Jackson as Mace Windu, one of the chief Jedi.

The comic relief is as bad as its reputation, if not worse. Jar Jar Binks is not just aggressively annoying, but his clown shenanigans and fart reaction faces usually come mere moments before or after stern line-readings by Neeson. With Binks and penny-pinching junk-dealer Watto, Lucas seems to operate under the assumption that if you recycle old pulpy racial caricatures as aliens, it’s no longer racist. And maybe he’s right: I certainly didn’t know they were racial caricatures when I was a kid, and I’m not sure I would have even thought of it as such as an adult if not for the various griping and numerous thinkpieces on the matter in the years since.

One aspect of the film I’ve taken a U-turn on for the worse is the many connections to the original trilogy. I used to think it was awesome that we got to spend more time C3PO and R2D2, and, wow, Anakin created C3PO! It’s so cool to revisit Tatooine and see a young Emperor Palpatine, my eleven-year-old self declared. Nowadays, it all makes me groan; perhaps some novelty and charm would linger if this kind of worldbuilding, nested lore and nods for the sake of it, hadn’t been the de facto storytelling mode of all franchised blockbusters of the past generation, but now I see it for what it is: lazy fan service that actually cheapens some of the old films.

I’m much more mixed on the production overall. I don’t deny that the CGI holds up way better than you’d expect from a 1999 film. This is not the same as saying it’s good, but honestly I might go that far. At a minimum, it’s all clean and easy to see, not as dim and brown as most blockbuster cinematography is these days. The setting designs are cool and varied, palatial and imaginative. And while he doesn’t quite get to War and Peace level scope like he wanted, the battles do feel appropriately huge. (“It’s gonna be great.”)

So almost all of the film is either bad or barely passable, but there are two sequences that are genuinely good. One of them because of Lucas’s work and one of them because of John Williams’ work. The latter, of course, is the lightsaber battle between Darth Maul, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and Qui-Gon Jinn. Whether this is actually an interesting fight scene in terms of choreography and production I’m a little mixed on, but damn if Williams’ “Duel of the Fates” doesn’t elevate it as one of the most epic and gripping scenes of the entire series. It almost makes me feel real human sadness when Qui-Gon Jinn gets laser-impaled.

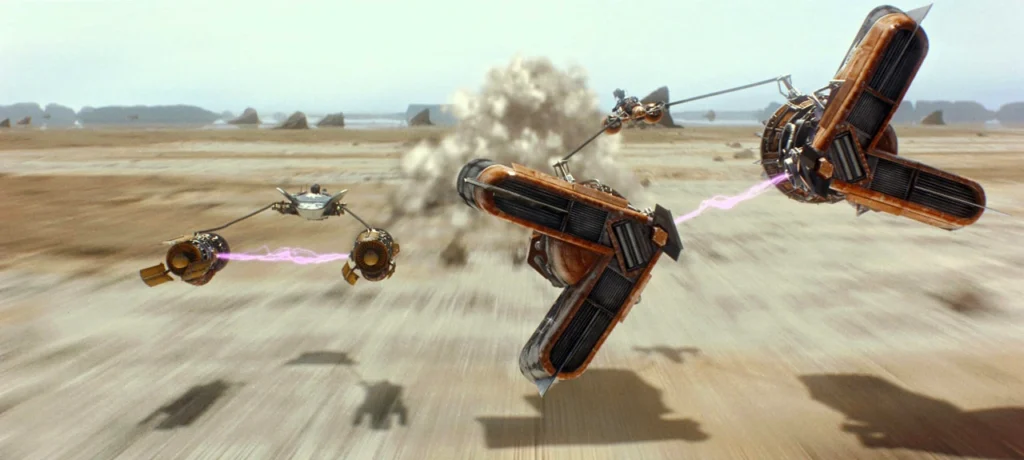

But the one stretch of film that I think works purely on filmmaking terms is the podracing sequence. It is exactly what I would hope a space Ben Hur chariot race would be, huge and screeching and dangerous. The sound design is remarkable, really tricking your brain into thinking you’re speeding through a canyon and on the cusp of dying in an explosion. I disagree with the common complaint that it runs too long. Given how good it is, I think its length is earned and just right. It honestly makes me even less patient with the rest of the film knowing that both Lucas and the technology are capable of this.

I think the acting is fine enough given all of the parameters — the unwieldy CGI, he laborious script, etc. Jake Lloyd as young Anakin has been unfairly maligned; he’s fine for what the movie asks. No actor actively makes the movie worse; we’d have to wait for the next prequel movie before that started. It’s no Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter on a cast front, but The Phantom Menace’s cast is an impressive collection of talent that props the film up.

Even outside those qualitative judgments, there are aspects about the film I hold close to my heart. I cannot, indeed, hack away all of the nostalgia. Boss Nass’s head shake was, and remains, an iconic moment of cinema to me. I have attempted to recreate the gesture hundreds of times. Also, we got a Weird Al masterpiece out of the movie, so I can’t be too grumpy.

But, like I said at the start, you don’t need me to give you an opinion on this film. You already have one. Everyone does. So here’s mine: It’s pretty bad! As much as I think Lucas’s work in the original Star Wars and American Graffiti has become underrated given everything that came since, I can’t get on board with the reappraisal the prequels have gone through (unlike Indy 4, which I do genuinely like now). But as problematic as The Phantom Menace is, it isn’t the series nadir. Uh oh.

Is It Good?

Not Very Good (3/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

10 replies on “Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (1999)”

I always appreciate a take on the prequels that holds the line and doesn’t capitulate to revisionism. I, too, was 10 once, but I’m not *blind.*

(I am, however, sympathetic to the idea that the *real* nadir of the series is The Rise of Skywalker.)

I’m reserving final judgment on Episode 9 until I revisit it, but am guessing I will not have it ranked last, though I’m not a defender. I am a little bit of a defender of the sequel trilogy overall, though. Episode 7 > Rogue One was one of my common movie argument battlefields in the late 2010s, but that’s one I’m not sure will hold up with revisit.

I probably prefer Force Awakens to Rogue One as well! Though in my case that’s more to do with indifference to Rogue One than affection for Ep 7.

Little A, little B for me

Not being an American of any stripe, I can only say that THE PHANTOM MENACE was the first STAR WARS film I saw in a cinema and that the next one was REVENGE OF THE SITH – and I recall enjoying both, even at the time.

Quite frankly I feel – and have always felt – that while THE PHANTOM MENACE isn’t the Best STAR WARS film it’s closer to the better films than the worst (Also that seldom in the history of feature films has a piece of cinema been so subject to excessively-close scrutiny, all too often spiteful).

To sum up: I feel no small amount of warmth for this film, but can accept that not everybody will feel the same (Also, Qui-Gon Jinn makes quite a bit of sense as a ‘drunken master’ type: think about it).

I like the idea of Qui-Gon as a drunken master, but I don’t think Neeson likes the idea! At least, he doesn’t play it that way.

I don’t begrudge anyone liking this one more than me! It’s funny how we all see these cultural monoliths from different angles.

I somehow saw this twice in theaters, and I can’t remember if that was because when I was 16 I thought it was good, or if my buddy and I had to go back to confirm that it wasn’t, but I vaguely recall being jazzed by the ending the first time, and that was the last recollection I have of any particular warm feelings for the film.

I have always maintained that while it wouldn’t fix every problem, and Phantom Menace would still be kind of bad, it would be closer to normal bad–and it would do the whole Prequel Trilogy’s story a favor–if Anakin were just already a teenage Force user here, flirting with Padme, making Jedi uncomfortable, and presumably already being played by Christensen (and potentially allowing him to create an actual character, why, even a protagonist, which the follow-ups of course don’t really quite do). Oh well, hindsight’s 20/20 I guess.

I do more-or-less think Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith improve and hit “normal bad.”

I can’t speak for ATTACK OF THE CLONES, but must confess that REVENGE OF THE SITH is one of my personal favourites – which I attribute in no small part to Mr Matthew Stover’s excellent novelisation putting everything quite beautifully in context for me.

I think you’re probably right that the protagonist problem is the root of it. I’m not convinced the solution is giving Hayden Christensen more George Lucas lines to deliver, but it would at least provide a throughline, especially if they let him be more teenage, less angst, for a film. Give us a baseline for his descent.

I do not think Attack of the Clones is better than this, but given that it’s broken in different ways, I fully understand thinking that.

Hey, if we *can* change Christensen in our counterfactual history, I’m not against it.