Pedro?

American Pie has “MILF” and the fucking of baked goods. Superbad has McLovin. And Varsity Blues has its own everlasting dumb image and line: first, a whipped cream bikini; and, second, “I don’t want your laife.” This is a film that lives in the cultural bloodstream for those reasons alone, some scrumptious near-nudity plus James Van Der Beek’s Texas drawl ringing into eternity. But Varsity Blues is more than a couple of memes, and even though it has a deep crisis of tone at its core that it never shakes, it still has some magic to it. It’s the Friday night lights and everything that goes with them: the zest of autumn, the terror of adolescence, the dreams of what we may become. I watch, and suddenly I’m back in the high school marching band, scarfing junk food after our halftime show and laughing at inside jokes. Brisk sunset fall air and stadium rock. I never went to parties like the ones in this movie, and I grew up in the mid-Atlantic rather than the heart of Texas, but Varsity Blues makes me nostalgic for my own adolescence. (Great title, by the way.)

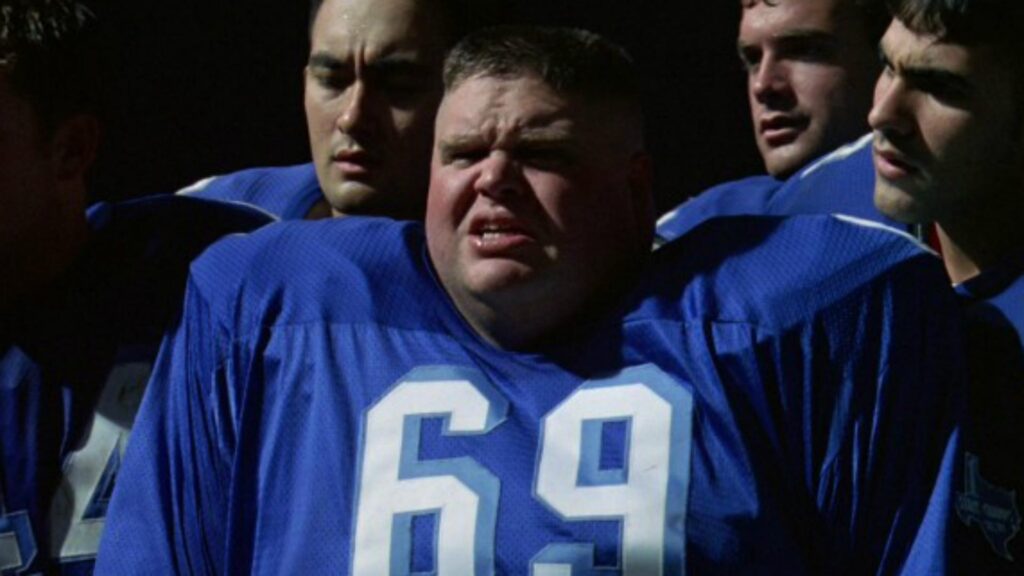

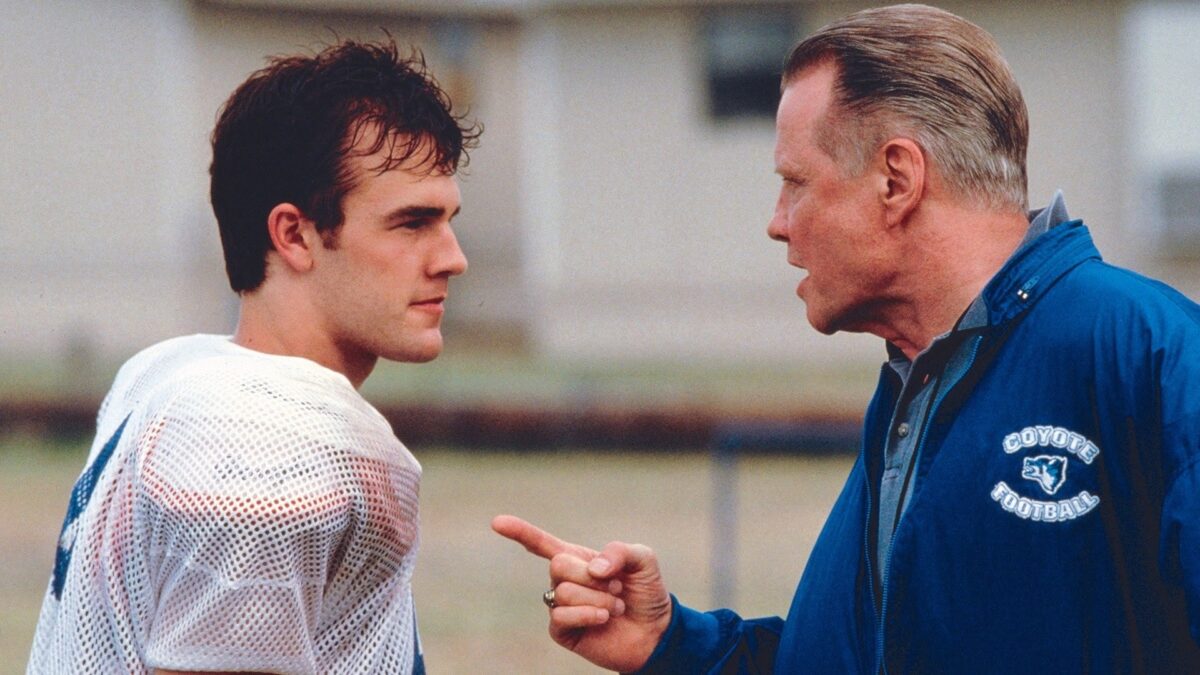

We meet backup QB Jonathan “Mox” Moxon (Van Der Beek), a bookish kid already halfway out of Texas exurb West Canaan, and tyrant-king Coach Bud Kilmer (Jon Voight), a growling taskmaster of win-at-all-costs smash-mouth football. Golden boy starter Lance Harbor (Paul Walker) floats through school hallways and kegger parties like a hometown deity, while lovable fat-ass lineman Billy Bob (Ron Lester) abuses his body for the team and for peer entertainment. Resident sex pest/one-liner cannon Charlie Tweeder (Scott Caan) is a loyal friend but a devil on Mox’s shoulder at every point. Mox’s girl-next-door love Jules (Amy Smart) tries to point him toward a future; head cheerleader Darcy Sears (Ali Larter) tries to point him toward her bedroom.

The logline, and occasionally the script, read as a filthy teen comedy, and Varsity Blues is certainly a specimen of that genre to some degree. But director (and later bigwig producer) Brian Robbins also steers the movie towards something more wistful and emotionally charged, and the subsequent struggle for Varsity Blues’ soul is fascinating. For a movie remembered as raunch-com sports pulp, the film is surprisingly cinematic and sincere: low angles of the gulping Texas sky and stadium lights, heat-wobble montages of farm equipment and practice dust, and a handful of bold push-ins and dolly zooms. In an early scene, Robbins and cinematographer Chuck Cohen turn a backyard cookout into a fever dream of curdling angst and crushing social expectations. The football itself is cut to feel like ritual sacrifice: slow-mo carnage full of wartime casualties. A post-party hangover gameday montage set to classic rock is almost certainly the best sequence of film that Robbins has ever directed: bodies flutter through the air like rag dolls while the camera watches with equal parts awe and concern at the kids’ crumbling fates (and bodily compositions).

Tonally, Varsity Blues alternates on practically a scene-by-scene basis between frothy comedy and more earnest light drama. Its ambivalent treatment of some of its football-specific content plays very odd in retrospect: It’s hard to know to what extent the movie knows that getting concussed or ruptured on Friday and injected on Monday was dooming its players to potential long-term brain and body damage, as the film genuinely reads both as dismissive and tragic from beat to beat. Voight (far and away the best performance in the film) plays the part of authoritarian dead-serious, refusing to turn Kilmer into a cartoon. He’s scarier because he believes in the gospel he’s preaching. Genuinely, this persona could be an SEC coach. When he hisses about “48 minutes for the next 48 years,” it’s easy to feel both the inspiration and fear that statement instills in these 18-year-olds. The movie also depicts the privilege of being a gridiron star in a football town: a cop declines to prosecute kids who carjack his cruiser so he doesn’t get shunned by the community, and convenience stores hand out six-packs to Mox and co. at no charge.

The teen-soap beats are less tidy, and I suspect earlier drafts of the screenplay played up the love triangle a bit more. Mox and Jules have a prickly rhythm that never fully resolves into a clear relationship dynamic; she’s alternately a sweetheart and a scold. Larter’s Sears gets her iconic whipped cream seduction moment (fun fact from production: it’s really shaving cream) and then, puzzlingly, exits the movie. But the male friendships feel lived-in: Walker’s low-key warmth gives Lance and Mox an easy, friendly rapport rather than the more narratively intuitive rivalry, a nice counterweight to the hyper-competitive testosterone depicted elsewhere. And when Billy Bob has a breakdown in the third act, it hits hard; Lester plays the clown wonderfully, then pivots to drama effortlessly, giving maybe the best teen performance of the film.

The movie’s climax is a bit sloppy from a narrative perspective, clearly rewritten a dozen times prior to filming. It really piles on the stakes: a halftime mutiny by the team against Coach Kilmer, an all-out last stand to defeat bullying and racism (oh yeah, there’s a race-bullying subplot), and a big speech from Mox about playing “for us.” It’s corny, but it sells the sports movie beats well. Do I wish it risked a weirder and more bittersweet final note, like its more serious cousin Friday Night Lights? A little. (According to Robbins’ commentary track, one draft of the script included less triumph and more melancholy in the closing scenes.) But the ending as written indeed satisfies.

It’s not a hidden masterpiece or anything, but I vibe with Varsity Blues. It has a pleasing and surprising blend of moods. I like its warm embrace of both sex comedy and earnest drama. It sharply captures a teenage mythology written in the bleachers and parking lots. It makes me long for my own high school years. Maybe that sounds like a bad time for you, but if so, well…

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Related Articles

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

3 replies on “Varsity Blues (1999)”

You had me at ‘Amy Smart’, but then you followed with ‘Ali Larter’ and her bold statement in post-match couture (By the sound of things they phased her character out right quick because the obvious Teen Comedy resolution to this particular love triangle would have been ménage a trois – and I doubt they’d have been able to get away with it).

Heck, you could probably get an entirely separate teen comedy/Film Noir parody called TWO BLONDES AND A KNOCKOUT out of that particular cast & situation.

The makeup team dyed Smart’s hear brown to make her more distinct from Larter and make her more of a “girl next door” type. I barely recognized her.

Would def watch Two Blondes and a Knockout. Teen faux-noir should be done more often — Brick is a lot of dark fun.

One must admit that all I have of TWO BLONDES AND A KNOCKOUT is the title, as well as a concept (‘Two clever ladies decide they can use a not-especially-bright athlete for Fun & Profit, but get a little too clever: mayhem ensues’).

It was, in fact, thought up in terms of plain Film Noir, but the notion of it as TEEN Noir might make it even better – for which refinement of the basic concept I thank you.

Heck, seeing Ms Larter and Ms Smart together in pictures from the VARSITY BLUES publicity cycle makes me wonder if they’d have been a natural double act on which to build such a (hypothetical) film.