Baz Luhrmann — born Mark Anthony Luhrmann; given the nickname “Baz” when his high school chums noticed his resemblance to the British TV puppet fox Basil Brush — grew up in a tiny Australian town called Herons Creek. While attending college at the National Institute of Dramatic Art, he landed some small-time film and TV spots. College was also where he wrote and produced his first original play in 1984: a 30-minute one-act story about competitive ballroom dancers.

That play, titled Strictly Ballroom, was a hit with local audiences. Luhrmann, using some money saved from his acting gigs plus some sponsorship money from his college, brought an expanded version of the play on the road, performing at a Slovakian festival in 1986 then at the Wharf Theater in 1988, where it caught the eye of a producer. Luhrmann agreed to sell the rights to the play so long as he was hired as the director and writer. Thus, in 1992, a few months before his 30th birthday, Baz Luhrmann’s debut film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, where it received a 15-minute standing ovation and a bidding war for its distribution rights.

The proof is in the celluloid pudding, and there is indeed something special about Strictly Ballroom, the first in the “Red Curtain Trilogy.” It has a lightweight charm that transcends the somewhat perfunctory and derivative script. If you’ve ever seen a dance movie, or even a sports movie, you’ll recognize and predict just about every beat here. The dialogue is squarely in the tradition of Austalian comedy: unmodulated, bantery, colorful, and (to my eyes) unexpectedly off-putting for being a bit mean. And yet Strictly Ballroom brings out the best in all of those things, thanks largely to Luhrmann’s direction.

Where Luhrmann’s next two pictures would represent a revolutionary approach to visual design in film and editing, Strictly Ballroom is strictly an evolution. But being on the inner bounds of conventional cinematic language is not really a bad thing, and it’s also no comment on the quality of the direction. Indeed, Strictly Ballroom is a kinetic and infectious film, and it unmistakably bears the director’s fingerprints we’d come to recognize: we get glittering lights and swishing fabrics and jolts of color, but subdued and mostly in service of realism.

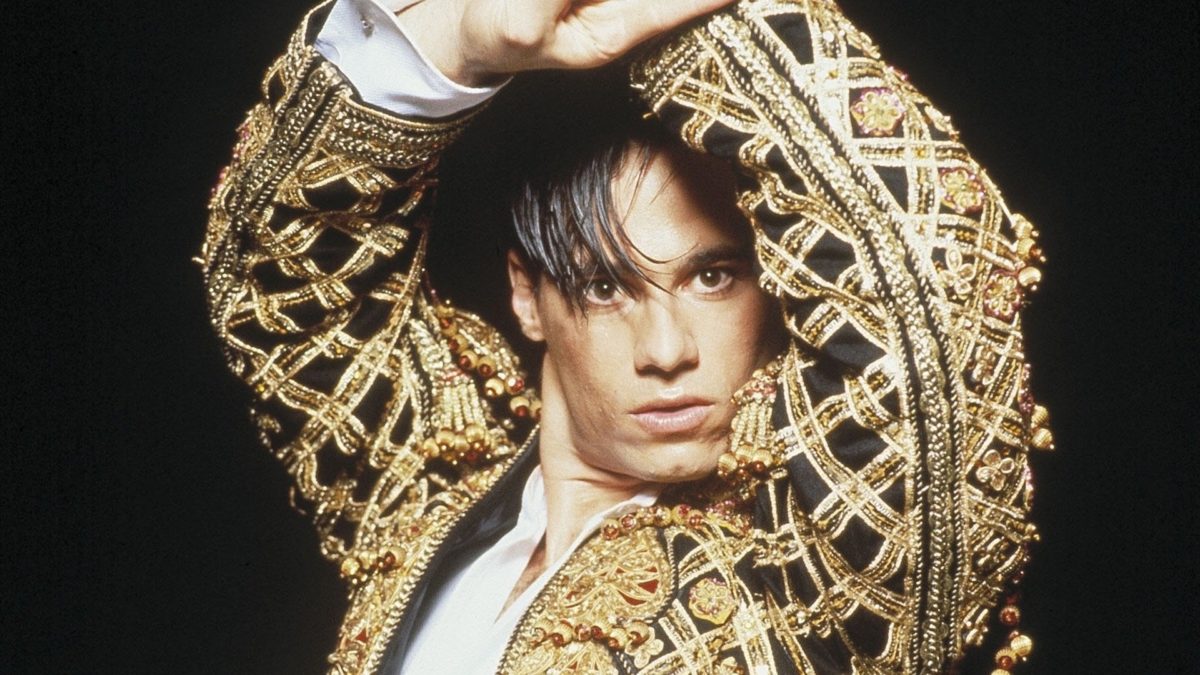

Paul Mercurio and Tara Morice star as protagonists Scott and Fran. Neither gives a particularly deep performance, but subtlety is not the name of the game here. The pair have terrific romantic chemistry; Luhrmann gives their faces plenty of close-ups to draw us into their emotional arcs. Most importantly, they get lots of time to dance.

There’s almost no overstating how good and crucial the dance scenes are in this movie. Luhrmann uses dance in a classical sense, letting music and moving bodies tell the story more than anything in the script. The film plays almost like a nondiegetic ballet in these scenes, as Luhrmann toys with cinematic artifice as a storytelling tool: The in-universe dancing is so heightened and theatrical, it steals the show from everything around it. Strictly Ballroom is not quite a musical, but perhaps a “dance-cical.”

There’s tension and physicality in the movements of the dancers, plus a technical precision brought on by the formal training of the cast (Mercurio’s background is as a dancer rather than an actor). We don’t need the script to tell us that Fran and Scott are the perfect partners, that they’ve achieved an enlightenment by breaking free of their rigid and repressive societal expectations. We’ve already learned all that on the dance floor.

The script is the film’s biggest rough spot. In addition to its formulaic, though functional, story structure, there’s a morass of forgettable side characters: potential and former dance partners, teachers in the studios, judges at competitions, etc. They all get a few lines and moments, but not enough for any of them to really stick. The major exception is Pat Thomson’s unhinged performance as Scott’s zealous, competitive mother. Sadly, Thomson passed away shortly before the film’s debut.

It’s easy to watch the bravura of Luhrmann’s later work and look back at Strictly Ballroom as a trifle, but that would be a mistake. Luhrmann, working in a mode of relative restraint, building towards a conventional happy ending, is damn fun. Effervescent. As we know, though, neither “restraint” nor “happy endings” would be too frequent in his future. Uncharacteristic though it is for what Luhrmann would become, Strictly Ballroom holds up as a terrific directorial debut.

- Review Series: Baz Luhrmann

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.