"I have a professional obligation to be malicious"

The extent to which Babe: Pig in the City hocks a loogie in the face of the original Babe is a very well-documented legend of modern filmmaking. And yet, even with this knowledge, there’s almost no way to properly prepare yourself for actually watching it. I have trouble imagining how it could be less like Babe in spirit while still serving as an actual sequel, short of being an intentionally transgressive anti-sequel made for adults rather than kids (and, come to think of it, that’s not the worst description for Pig in the City).

What do I mean? Well, remember the warm storybook mise en scene and narrative logic that made Babe so inviting? Here are a few plot events in Pig in the City: Farmer Hoggett (James Cromwell) suffers a near-death spinal-mutilating fall because of Babe’s cluelessness; Hoggett’s wife Esme (Magda Szubanski) flies in desperation to the big city Metropolis to financially exploit Babe’s fame or else lose the farm to creditors; a drug-sniffing dog that Babe befriends turns him and Esme in as traffickers for no reason except that he’s bored and gets treats when he identifies a culprit. This all happens in the film’s first ten minutes. The cruel punches do not stop rolling in for the rest of the runtime. I concluded my review of Babe with a backhanded compliment towards its “uncontroversial kindness” — no one would ever use that phrase for its sequel.

It’s all a bit mean-spirited, and yet Babe: Pig in the City is also miraculously good. Almost all of its success comes down to the prodigious skill and creativity of George Miller. Unlike Babe, Miller is the credited director; no need to retroactively tussle for credit, though I’m not sure there’d be so much desperation to have this film serve as your legacy as there was the original. Miller, in his final live-action film until Mad Max: Fury Road seventeen years later, displays his unconventional worldbuilding and visionary set piece construction. (As scattershot as his career is, a zoomed-out view does paint a picture of a singular director gradually expanding and refining his one-of-a-kind creative toolset in a steady arc, even as each film itself is idiosyncratic.) And, like nearly all of Miller’s films, Babe: Pig in the City revels in its excesses and strange curves.

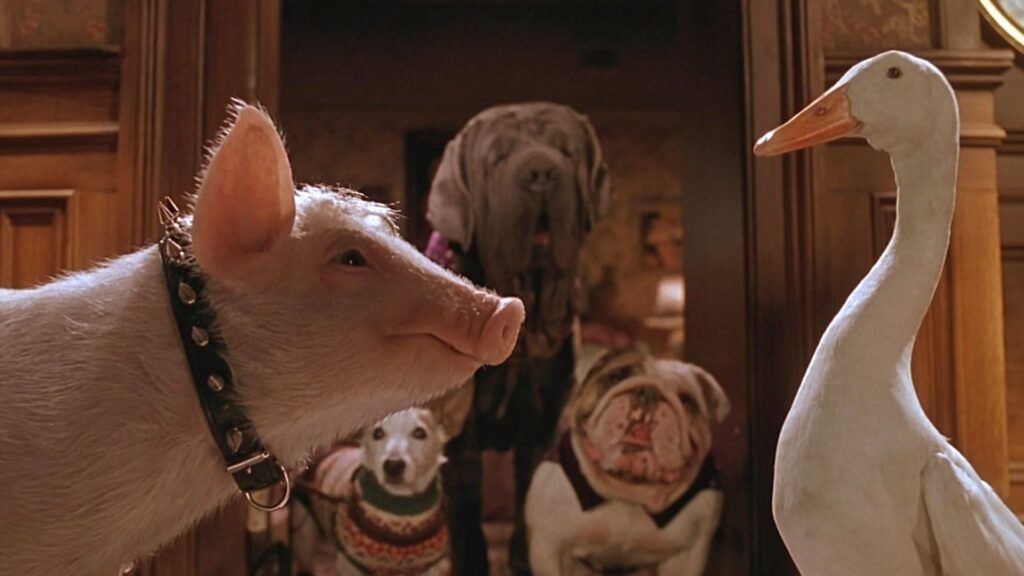

The animal “movie magic” of the original Babe — a blend of animatronics and real animals seamlessly interacting with the human world around it — is even more impressive than before. I still have no earthly idea how Miller pulled it all off: The variety of animals, the sheer numbers of them onscreen, and the complexity of their actions has grown dramatically between films. The blocking and stunt choreography and scene construction on display would be a marvel even if these characters were humans or CGI constructions; that they are real-life dogs and monkeys and pigs borders on the impossible.

Even beyond that, Pig in the City is an enormous triumph as a production. The sets are tinged with expressionism but all part of an enveloping whole. The costumes are fun. A rescue in a river is genuinely harrowing. There are a few effects that pop off the screen in visceral tactility, like a goopy substance that entraps Esme. Some of Miller’s direction is outstanding; watching the action, I even detected a few whiffs of the kinetic glory he’d achieve with Fury Road down the line (something he would build up to in the Happy Feet movies, as well).

Babe: Pig in the City’s story is episodic. The original Babe’s was, too, but these episodes are much more diverse and diffuse than before. Babe (now voiced by E.G. Daily) gets roped into a performing clown act. A butcher abducts him. He faces down animal control, who wants to cage him for the rest of his days. Abused and neglected animals turn to him for salvation. Every turn is bleak. But there is some strength in this: Witnessing Babe’s generous character persist through misery makes his kindness more touching than it ever was in the original.

There is a major wrinkle in my reading of the film that makes me much more receptive to it: I see this story as George Miller reflecting on his own filmmaking career. Babe is Miller. Both are Aussie countryside heroes who made their own unconventional paths. Both packed their bags for glory and riches in the big city, Metropolis/Hollywood. Both find not an easy road to fame and fulfillment, but a cruel and chaotic system with no patience or benevolence. Neither ever fully fits in, and both stick out like sore thumbs. Babe and Miller are paraded around and exploited, his own ambitions and achievements degraded. Yet each perseveres and wins people over by bringing their hometown countryside magic to Metropolis/Hollywood. Or, more precisely, they take some of that big city razzle-dazzle to their native place. With this film’s ending, Miller declares: He will work on his terms, not theirs.

It’s more complicated than that, though. While the way that Miller paints both his protagonist and his own life story as ultimately noble and valuable, there is quite a bit of self-mockery in this portrait. As a sequel, the film parodies the original and, as a result, Miller self-deprecates. He takes a sledgehammer to the heartwarming magic of the original — “baa ram ewe” gets laughed at and ignored, “that’ll do, pig” is self-consciously and artificially bolted on at the end. He references his other films a couple of times, like when Babe gets a Road Warrior extra-esque spike collar, or a late balloon-filled sequence that visually quotes The Witches of Eastwick. That Babe cannot fit in Metropolis is as much Babe’s own fault as it is the fault of the denizens and institutions of the city. How dare Babe take himself so seriously? Why would he think a humble pig with so minor a talent as shepherding would have any worth in the busy lives of everyday people with bigger problems in their lives? Just who does Babe, a false messiah for much of the story, think he is; and just what does Miller think he’s doing with his self-seriousness?

Babe: Pig in the City was divisive upon its release, and it remains so. Siskel and Ebert both adored it: Ebert gave it four stars and Siskel called it the best film of 1998 — you know, the year that also gave us The Thin Red Line and The Truman Show and Saving Private Ryan and bunch of other stone cold classics. But plenty of critics panned it, and it has a negative audience score on Rotten Tomatoes. It ranks well below median in most rankings and fan appraisals of the director’s filmography. I’d personally place it in the upper half of his work, though only by a bit.

Babe: Pig in the City is a film that’s more fascinating than it is great, but it is certainly the latter, too. Afterwards, Miller would stick with family movies as his various other projects churned through production hell. It would take almost a decade before Happy Feet came out, with Happy Feet 2 a few years on its tail. But Miller’s very best was indeed yet to come.

- Review Series: George Miller

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.