Holy rollers

Is it the end of the world, or just a weeknight? That’s the question at the center of Happer’s Comet, the second feature from Ham on Rye oddball Tyler Taormina. It’s also a refrain many of us have uttered on loop since 2020. Happer’s Comet bears no clear signs of COVID: no masks, no Zoom windows, no sourdough starters. And yet this is Taormina’s pandemic film, the one that bottles the dissociation of lockdown in tiny vignettes. The apocalypse isn’t sirens and explosions; it’s a neighborhood that looks normal on the outside, empty on the inside.

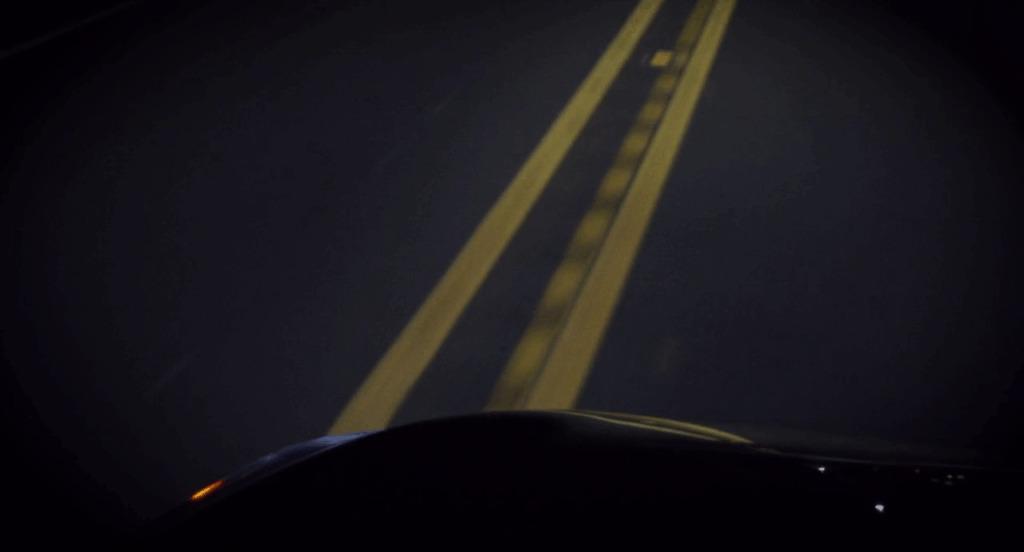

Taormina sketches a small town in near-total darkness and watches its residents do almost nothing. They vacuum, smoke, count money, listen to the radio. A phone records night sounds from a windowsill. A car idles. Someone types “what do I do about my…” into Google and stares at the predictive results like it’s a choose-your-own malady. Stalks of corn on the side of the road tumble into the distance and wave in the wind: The movie calls particular attention to this latter image, as one of the film’s first shots is a close-up on a rotting ear of corn. A small handful of images recur: reflections, chairs, roads swerving towards a horizon.

The movie’s only recurring “plot” thread is that several people feel beckoned to glide through the empty streets on roller skates (one of whom is played by Taormina himself). We wonder if any of them will cross paths, but they never do. Every so often the camera glances up: a long-tailed comet hangs in the sky, indifferent and beautiful. We never learn whether it’s a momentary astrological phenomenon or a sign from God, and we sense the residents are just as curious and hopeless to understand it as we are.

Happer’s Comet drifts further into the non-narrative, avant-garde territory that Ham on Rye toyed with in its second half. There, the emptiness played like a mystery: what happened to the kids from the first half, and what happens now to the people left behind? Happer’s Comet doesn’t even have that hook. The tension is even more unspoken: What the hell explains *gestures broadly*? But, like the second half of Ham on Rye, no coherent answers ever take shape. Festival curators acknowledged this lack of narrative shape and typically categorized Happer’s Comet as an experimental work when scheduling it. The film premiered at 2022 Berlinale Forum, the influential avant-garde program at the Berlin Film Festival. A limited 2023 American run followed.

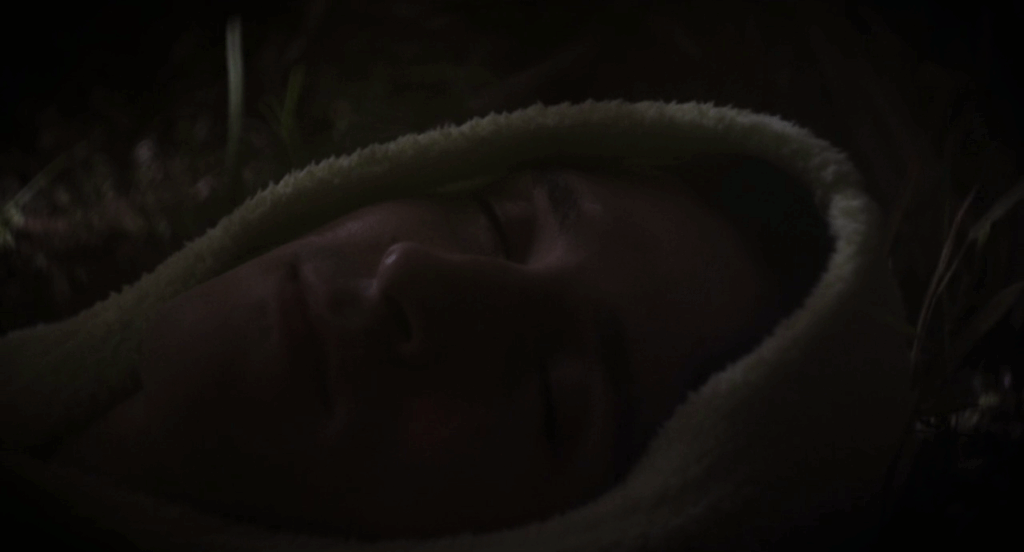

My favorite aspect of Happer’s Comet is its relationship with darkness. The darkness here isn’t a device of fear or danger or even the unknown. Instead, it’s an agent of alienation. Taormina and cinematographer Jesse Sperling carve the night into dimly lit pockets separated a black void, much like its people exist in lonely bubbles. (Social media might call them “liminal spaces.”) This actually matches my experience with late-night darkness: I am rarely frightened of it, but it makes me feel like I’m in a world all by myself. Because this entire film unfolds between dusk and dawn, every snapshot feels like an insomnia portrait: bodies out of rhythm, circadian clocks gone haywire, people whose minds can’t power down even if the town has. That temporal dislocation lines up with the visual work the light (and its absence) is doing.

Later in the film, the movie finally shows two humans onscreen at the same time, and it feels like a forbidden pleasure. In a cornfield, in the dead of night, two people embrace, a scene staged and shot with the intimacy of a sex scene. But they’re just hugging. The contrast with the loneliness that makes up the rest of the film, plus the strange texture of the cornstalks at night, makes this an extremely powerful moment.

Taormina applies very little rhythm in the editing. That looseness can read, moment to moment, like noodling. It also gives the film permission to exist as a tone poem, a long, low chord of suburban ennui. Happer’s Comet always feels like it’s lingering so we can properly feel its audiovisual textures: a vacuum’s hum drowning out a room; the grain of streetlight across a face; the flicker of a phone screen slightly shifting the shadows. If you’re waiting for momentum, you might fidget. If you surrender to mood, the movie rewards you with a very specific spell.

The production itself is about as stripped down as it gets. Made on the tiniest of shoestrings, nearly everyone involved, cast and crew alike, were friends, family, and community members from Taormina’s Long Island hometown. He collaborated with cinematographer Jesse Sperling, his partner from earlier shorts, while shouldering most of the production and post-production credits. Most shoots were nothing more than Taormina, Sperling, and a single performer. The resulting minimalist look works well enough, offering a haunted, melancholy visual timbre, though I dearly miss the blissful cinematography of Carson Lund from Ham on Rye. I’m glad to know Lund returned for Taormina’s third film, Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point.

The ending arrives anti-climactically; to expect otherwise would be to misunderstand Taormina’s sensibility. Dawn comes, the world persists, and a boat floats into the sunrise. This last image is not a location or object we’ve seen before, so it bears no structural symmetry or narrative payoff, yet it still resonates with portent; currents of inevitability and loneliness persist. I often say a car driving into the horizon is the perfect image to close a film; what we get here is in that same spirit.

All film is subjective, but non-narrative cinema is especially so. If you connect with an experimental film’s vibe, it can feel like a direct line into your heart, triggering emotions in ways both unpredictable and powerful. And if you’re out, it can be the most tedious and pretentious experience on earth. Taormina’s explorations of suburban ennui strike me in exactly the perfect way. I completely love both of his films I’ve seen, even while acknowledging that others may not respond as deeply. To my eyes, he’s one of the most fascinating young filmmakers on the planet. Happer’s Comet is deliberately a minor film, built from puzzle pieces and glimpses, yet those fragments accumulate into something wonderful.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “Happer’s Comet (2022)”

I’m intrigued, at any rate.

And it’s only 62 minutes 😲

I’ll admit it sounds kinda cool.

Would’ve gone with “Prayer of the roller boys”!

Had to look that one up but, man, yeah, fits perfect.