Community

Season 1

Pilot (S01E01)

I can't count the reasons I should stay

I was a senior in college and a devotee of NBC’s Thursday night programming in September 2009 when Community premiered.

My degree was in math, computer science, and education, but my love was writing: I was an editor and columnist at The Cavalier Daily, the college newspaper for the University of Virginia, and had just started a pop culture reviews blog with a couple of my friends.

In particular, I really loved writing about TV comedy, and indeed, I dreamed about writing my own comedy scripts someday. I have about half a dozen spec pilots stashed in the depths of my hard drive. In my early 20s, I was deeply fascinated and entranced with shows that used sitcom structure as its bread and butter, but wrapped it in some sort of formal or dramatic ambition, and the late ‘00s were good eating for my tastes: How I Met Your Mother both leaned the hardest into its genial, over-familiar sitcom tone and offered the highest concept pitch tying it together, with immensely clever variations and subversions on conventions from episode to episode. Parks and Recreation brought a community to life with an outstanding ensemble of characters and imbued it with Obama-era optimism on the restorative power of public service. Scrubs offered an idiosyncratic voice and sense of humor paired with multi-episode stories and gutting blasts of medical drama pathos.

But the real standard-bearer of ambitious sitcomming was The Office, both versions. The British show, which is in my esteem one of the greatest and most important pieces of filmed entertainment of the 21st century, kicked off the trend of TV comedies daring to do more than the misadventures-of-the-week that sitcoms historically relied upon, inverting the “nothing ever changes” and “doofuses abound” tropes into a meditation on dull modernity, aimless ennui, and the hope of something romantic and life-changing breaking through that malaise. The American remake was warmer and more sprawling, and remains one of the most cinematic and emotionally developed network comedies ever made. It’s been a bit overexposed from memes and eternal streaming re-runs, and it definitely had bouts of filler and plenty of storytelling mistakes, but all of that’s just part of the long-running TV show experience, and it doesn’t shake The Office’s status as an all-time great TV show.

Thus, Community was premiering in an ecosytem of great TV comedies, particularly at NBC: Its first season aired in a 2-hour block that also included Parks and Rec (Season 2), The Office (Season 6), and 30 Rock (Season 4). That’s just a generational lineup, though this would only become obvious in retrospect. TV was still reeling from a writer’s strike that had ended just a year earlier; Community was new, and Parks and Rec had received middling reviews in its short first season, though, like The Office, it would properly find its voice in its sophomore season.

Four years after Community’s pilot aired, Netflix launched the first major streaming-only show, Orange is the New Black, sending TV into a cataclysmic shakeup

What we didn’t know in 2009, and most profoundly shapes that era’s legacy, was that Community was premiering during the last great age for network television. Four years after Community’s pilot aired, Netflix launched the first major streaming-only show, Orange is the New Black, sending TV into a cataclysmic shakeup that would render anything resembling a traditional sitcom not a part of the frontline of television, but, instead, a dinosaur; an ancient boomer-coded relic. Streaming changed everything: episodic stories were out and serial stories were in. A lack of commercial breaks allowed inconsistent runtimes, a freedom that must have been liberating in the short term but resulted in the slow dissolution of the three-act structure in TV. Full-season productions and episode dumps became the norm, meaning shows had little chance to evolve and improve. With streaming, the entire business, consumption mechanisms, and distribution model of an art-form that had been largely untouched for 60 years transformed into a bizarre hybrid between broken-up television and single-story movies. Sometimes it works, but sometimes brings out the worst of both formats. The average streaming TV show (though certainly not all of them) is padded, clunky, poorly paced, and 25% of the way towards cinematic without actually delivering the spectacle and allure of proper cinema. The proliferation of quasi-movie-TV eventually pushed me away from the diminishing returns of streaming shows and towards movies, which I could at least finish in two hours instead of the eight-plus hours required of a TV show. And I discovered that the average 2-hour film has similar amounts of meaningful story to appreciate compared to the average 8 hour season of streaming TV despite those time differences.

In fact, Community would eventually get sucked into the streaming vortex, though it would mostly keep its shape. But that was several years off from the pilot. Community’s story starts in 2009, back when annual TV cycles had distinct, seasonal beginnings and ends: Shows would premiere in the fall, release twenty-some episodes weekly through the spring with intermittent breaks, and conclude with “sweeps” around May. Sweeps was an important time for traditional TV, as it was when shows made their big push to capture eyes (and ad revenue) in order to get renewed by networks. And Community’s first season sweeps definitely showcased the show’s ability to take swings.

Community earned significant media buzz prior to its debut because of the casting of comedy legend Chevy Chase as a series regular. It was a comeback for the biggest comedy star of the 1980s, a man whose name alone was a brand for a certain flavor of feisty, sharp-tongued wit. The model for his casting was unquestionably Alec Baldwin on 30 Rock: You take an aging but beloved Hollywood actor of dimming fame and plop him in a sitcom to both an older generation that adores him and a younger generation who can get to know him better. Baldwin reinvented himself and catapulted back into the spotlight on the strength of an instantly iconic NBC sitcom character. If Baldwin could do it, why not Chase?

I was one of the people hyped for Community thanks to its cast, but not because of Chevy Chase, who I had seen in a few movies played on cable TV, but who was not at all an icon to me, personally. No, my interest came from two other cast members: First and foremost was Donald Glover, who was not yet a household name but whom the comedy industry had pegged as a future star. (This projection was correct, but probably not how anyone guessed.) Glover had made TV industry connections as a member of the Upright Citizens Brigade while a student at New York University. The UCB circa the 2000s was a remarkable incubator for future TV talent; an astonishing number of future TV comedy stars had their start in the group. But where I knew Glover from was an online sketch YouTube channel called “Derrick Comedy” that Glover had formed with his NYU buddies; the slightly absurd, slightly transgressive skits played on loop on my college laptop. I still have many of them memorized. The sketch group had an upcoming feature film, Mystery Team, so my Derrick Comedy fever was at an all-time high in fall 2009. Glover was clearly the funniest of the group; sketches sometimes boiled down to Glover lighting up the screen like a comic lightning bolt for a few minutes, like Jerry, where he plays a student who pooped his pants.

Glover earned a gig writing for 30 Rock then was poached for Community, where he figured to be the comic sparring partner with Chase (an assumption that you can prominently see in the show’s first few episodes before the writers quickly realized Glover’s better chemistry with the younger members cast like Danny Pudi).

The second cast member I was excited to see more of was Yvette Nicole Brown, whom I knew from the Nickelodeon tween sitcom Drake and Josh, which I adored as a teenager (and which still holds up). Brown was a regular scene-stealer as Josh’s boss at his movie theater job, her emphatic line deliveries and screen presence overcoming a character that maybe leaned a bit too hard on “sassy Black woman” beats.

One name I did not know at all at the time of Community’s pilot was Dan Harmon, who would ultimately use the show to springboard himself as one of the most revered comedy showrunners in all of television. Harmon had co-created the boundary-pushing Comedy Central sitcom The Sarah Silverman Program and done a ton of underground work and some scriptwriting (co-writing the 2006 animated film Monster House). He served as the sole creator and visionary of Community at age 36 — a young age for a showrunner on a major network, though not preposterously or historically so (Josh Schwartz was 26 when The OC debuted). Though he’s built a following (particularly on the popularity of his subsequent show, Rick and Morty), Harmon has always been a divisive personality: He has a well-established reputation as an opinionated perfectionist who speaks without filter, and so it’s easy to imagine another big personality (read: Chase) feuding with him. But if you’re a fan of his work, Harmon makes for a delightful face of the product. During his Community tenure, he regularly gave memorable interviews filled with sound-bites that would garner headlines and headaches for NBC’s PR managers, but always invigorate fans. Community’s shooting was known for long shooting hours with many takes, last-minute script deliveries, and Harmon’s sheer force of will shaping every facet of the show — and these are what allowed the show develop its bracing energy and polish. Harmon was also an alcoholic at the time, which surely contributed to his volatility and notorious mean streak, though it hardly interfered with his ability to manage an incredible room of writers and consistently turn out great scripts.

All of this brings us to the show itself. Rewatching Community in 2025, somehow 16 years later (time is a flat circle), the first season reveals itself above all as a specimen of tension. The show is fighting against itself, especially in this first season, trying to figure out to what extent it’s a normal single-camera sitcom that is a few degrees sharper, more adventurous, and more self-aware than your average half-hour comedy, and to what extent it is a sui generis, boundary-less, genre-warping work of invention that sometimes barely even fits the “TV comedy” mold. Traditional done cleverly vs. radical done recklessly.

Community couldn’t have had an episode of a paintball war shot like Die Hard if it didn’t also have a normal but well-executed episode about a debate club

Of course, those are really not opposite ends of a spectrum, but layers of a pyramid: The biggest swings only have impact if they build on top of the show’s rock-solid fundamentals. Community couldn’t have had an episode of a paintball war shot like Die Hard, an immensely entertaining and revolutionary half hour of TV, if it didn’t also have a normal but well-executed episode about a debate club feud with an opposing school. The latter may get less love in the moment and in retrospect, but it sets a baseline reality for the experiments and genre-busters to upend, and is thus just as essential, if not more so.

But neither of those episodes would work if the show didn’t have well-defined personalities and dynamics for its large ensemble of characters, and that is the chief achievement of Community’s excellent pilot episode: It almost miraculously gives us clear, if in-progress, portraits of each of its seven main characters, plus introduces us to a couple of key supporters.

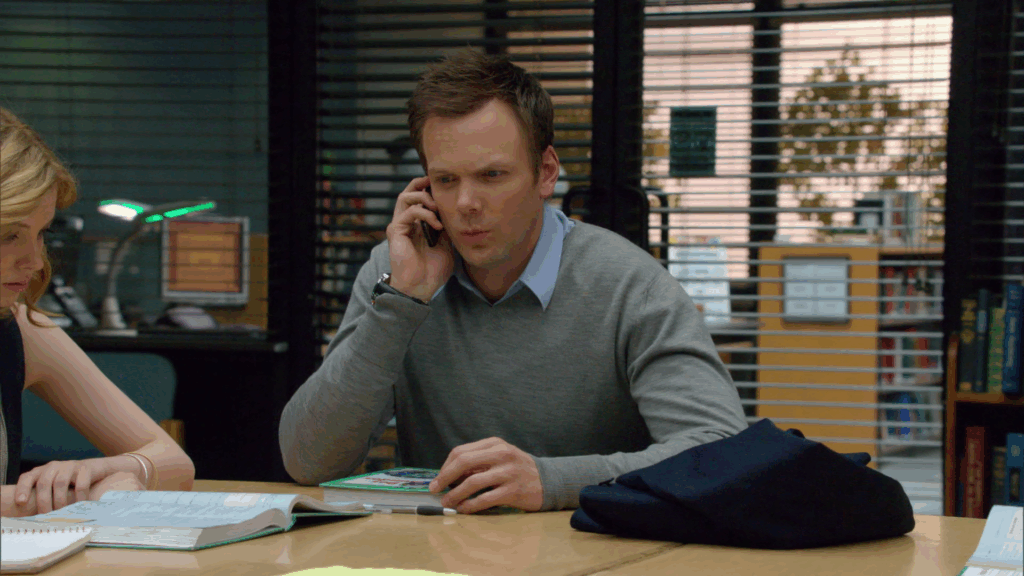

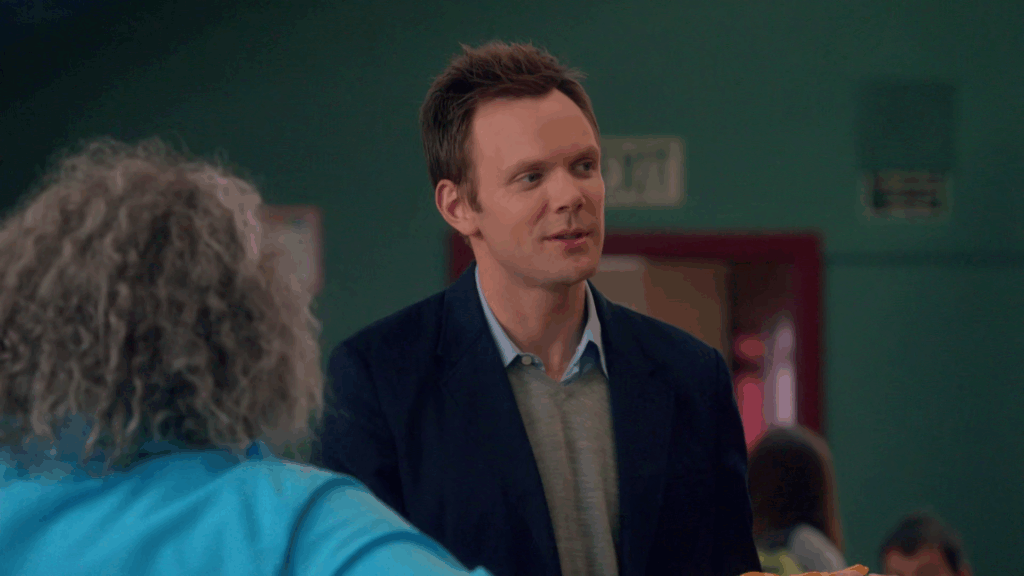

Our entry point into Community is Jeff Winger (Joel McHale). Winger, besides having an all-time great TV character name (up there with Barney Fife and Don Draper), is a cipher for Harmon, and thus the heart of the show, especially in its early run. We learn in the opening minutes of the pilot that Winger is an ex-hotshot lawyer who had faked his college degree. When the truth of his faux-ploma emerged, he was forced to enroll in a local community college. Thus, the man whose job it recently was to be the cleverest and most charismatic man in the room is now stuck at TV’s most humble (and humiliating) institution of education, Greendale Community College, which Jeff describes as a “school-shaped toilet.”

Jeff is a specimen of tension, just like the show: The writers and McHale are not sure where his head is at here. They know he is complicated and filled with contradictory impulses, but they haven’t sorted out the details yet. Is he above it all, cooler and slicker than everything around him? Or is he despondent and defeated by his circumstances? In the pilot, it’s a bit of both, which is captured in his wardrobe: gym pants with a business casual top. The commentary track with Harmon, McHale, and the Russo brothers, who directed the pilot (yes, the Russos of Avengers), reveals that this outfit was much debated as nobody had quite locked in on Jeff yet. And honestly, that’s just fine for a pilot.

The pilot is split, approximately, into three stories, which are all linked together: The first is Jeff meeting and trying to seduce the beautiful blonde Britta (Gillian Jacobs). The second is Jeff trying to coerce his former client, Ian Duncan (John Oliver), a professor at Greendale, into giving him all the exam answers for his courses so he can weasel his way through college. The third is Jeff inadvertently creating a Spanish study group as part of his attempts to woo Britta. We also get a glimpse into Greendale’s operations: A chipper but pathetic Dean (Jim Rash), who makes over-cheerful announcements over a loudspeaker like he’s a principal at an elementary school, runs the place. The dean is a small figure in this episode but would eventually be one of the show’s breakouts.

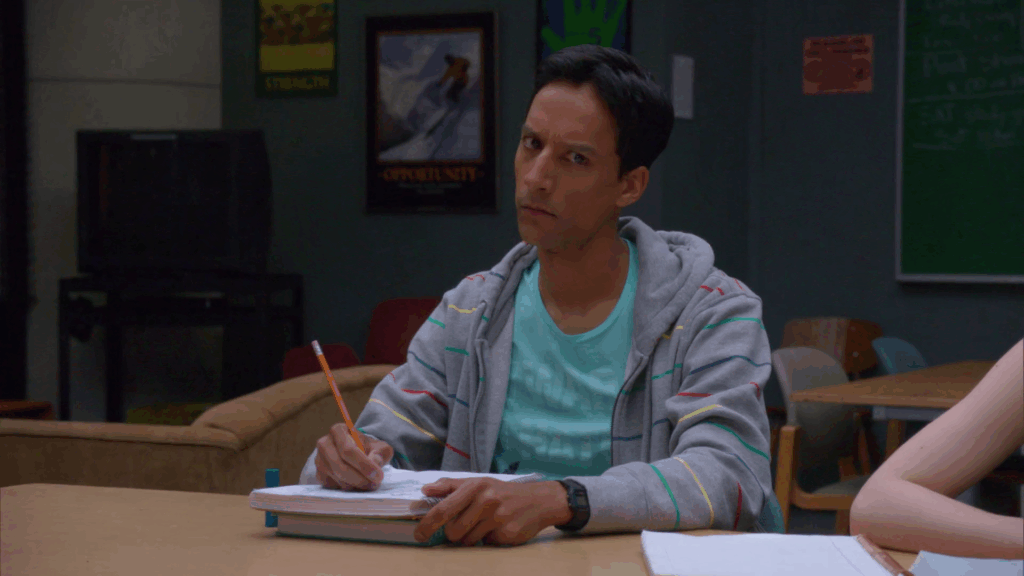

Let’s meet that study group, the show’s center: Annie Edison (Alison Brie), the young, anxious, type-A goody two-shoes; Shirley Bennett (Yvette Nicole Brown), a single mom; Pierce Hawthorne (Chase), a loopy old man whose business success has insulated him from reality; Troy Barnes (Glover), former high school golden boy and an airhead; and Abed Nadir (Danny Pudi), the socially awkward dork who filters life through pop culture references. Add in Britta and Jeff, and you’ve got seven personalities for the pilot to corral, sketching out the chemistry that already feels like it can power a hundred episodes’ worth of bickering and riffing.

What jumped out at me this rewatch is how cleanly the pilot seeds contradictions in each of the seven, little complexities that will become story engines and room for the actors to find their own version of the character. Annie, despite her positive and driven personality, is a bit antagonistic, and given a dark edge: She is rebuilding her life after a pills addiction spiral (technically Adderall, though the show pitches it closer to Jessie’s “I’m so excited!” caffeine pill habit from Saved by the Bell). Shirley’s sweetness is a mask over a violent streak, her church picnic warmth a facade for a temper. Chase gets the show’s riskiest assignment: a Grade-A boomer who can’t read the room and commits numerous violations that would get him sent to HR if this were a workplace comedy; and yet the pilot trusts Chase to make him likable, making space for Pierce’s off-kilter wisdom without sanding off the splinters of his impertinence. Troy hasn’t realized that he’s at risk of becoming a has-been who peaked in high school. Jacobs’s Britta, meanwhile, is so tied up in her principles that it becomes performative.

In some moments Abed is the omniscient narrator, the character who can see the TV show as a TV show, but who still fully participates.

Lastly, there’s Pudi’s Abed, who arrives already the most memorable and distinct character. Abed is pretty heavily autistic-coded throughout the series, but almost never verbally diagnosed as such — the pilot gets as close as Community ever comes to doing so, with Jeff dropping the now-outdated “Asperger’s” tag. And yet there’s something more to the character, even in the opening minutes: Winger calls him a “shaman,” and one of the show’s greatest strengths was Abed warping the world around him to pull off pop culture gags and meta jokes. In some moments he’s the omniscient narrator, the character who can see the TV show as a TV show, but who still fully participates in it. Pudi threads a tiny miracle, deeply funny and likable, but always keeping the show in a comic space charged with irony and self-awareness. Abed makes meta-jokes that actually celebrate what the show’s doing rather than debasing it. This essentially allows the show to work on two tracks at once, sincere execution character-driven comedy and a jokey deconstruction and recontextualization of such. The pilot’s take on Abed is not quite fully-formed (the Breakfast Club joke is a little on the nose), and the show’s ability to remix other pop culture beats and structural gags in with typical sitcom stories would take a while to fully germinate. But it’s easy to see the Harmon and the writers starting to figure it all out.

For all the strengths in the character writing in the pilot, nobody is the version of themselves you probably remember from the show’s peak. Annie is dialed so far into uptight that none of Brie’s sweet charm shines through. Troy, meanwhile, hasn’t yet calibrated his funniest version of dopey; he’s still playing “fallen jock” more than “goofball poet.” And you can make similar observations on each of the leads. But the seeds are all there, and, importantly, they’re interesting to spend time with rather than exhausting. No great sitcoms come perfectly shaped out of the gate. They’re all also likable, making you want them to thrive: Each of the seven is flawed, but on a redemptive arc like Jeff.

The group dialogue is simply better than almost any other sitcom of its era

What the pilot absolutely does understand from the start is that Community works best with the full ensemble. Like Cheers before it, it’s built around a single shared space, the instantly iconic study room, which becomes the gravitational center of the series. Nearly every episode of the show parks the whole group around that table at least once, and in the pilot those scenes are already the knockouts. The group dialogue is simply better than almost any other sitcom of its era: overlapping riffs, multiple conversational threads running in parallel but easily tracked, everybody talking in their own very specific voice, and somehow Harmon and the writers land the plane with a killer punchline or two every time.

The pilot also introduces a few narrative structures and recurring bits that would become part of Community’s house style, and then, in classic Community fashion, become tropes for the show to parody, deconstruct, and abuse until they resemble abstract art. The big one here is the Winger Speech: Jeff can often be counted on to deliver a quasi-sincere monologue in the third act that gathers the story’s various themes together with wit, tying the episode’s emotional thread into a bow while a gently uplifting score by Ludwig Göransson (yes, the Oscar winner) swells underneath. This first episode gives us one of the best Winger speeches of them all, what I call the “Shark Week” monologue, in which Jeff simultaneously observes and sarcastically mocks the inner dignity of each member of the study group.

For me, there are really two big misses in the pilot. The first is Oliver’s performance as Duncan. Some of this may just be his particular British vinegar, but he’s always felt too sour for a show that thrives on balancing a bunch of distinct tones at once. Oliver is, of course, a talented comedian, and based on the commentary tracks on the show’s DVDs, the writers and producers were ecstatic any time they could cram him into an episode. But Duncan’s petty cruelty doesn’t land as endearing the way the Dean’s does. Rash plays pathetic as almost cuddly; you root for him even as he humiliates himself. Duncan, by contrast, feels like a guest from a meaner series. Even Professor Chang (Ken Jeong), an actively cartoonish character introduced in the second episode and who has always been controversial among fans, fits in better with the show’s various wavelengths better for me than Duncan ever does.

The second miss is the supposed romantic spark between Britta and Jeff, which the pilot wants us to buy much more than the actors or writers can figure out how to sell. They’re no Dawn and Tim. Jacobs is one of the funniest and most versatile performers in a cast full of ringers; she can be a perfect straight woman or a complete clown depending on what the scene needs. But Community took a while to home in on her frequency. “Dreamy, damaged hippie angel who will redeem Jeff with her principles” is just not it. McHale, meanwhile, does smarm and vulnerability extremely well, but their screwball ping-pong dialog with these earlier takes of the characters never feels like the seeds of a grand romance. I have often speculated that NBC encouraged Harmon and co. to build a will-they-won’t-they romantic tension at the show’s core, as it really is one of the most reliable ways to build long-running intrigue in a sitcom. It took most of a season, but the show gradually figured out that long-running pining wasn’t the right dynamic for the pair.

Community arrives as a recognizable version of itself, and that’s no small feat.

And yet, overall, this is a minor miracle of a pilot. I deeply love it in part just for the nostalgia of that time in my life and for reminding me of the growing week-to-week thrill of witnessing the show grow. It’s especially impressive as a debut, given how rough sitcom premieres tend to be. For every great sitcom that absolutely nailed its first outing — Cheers, Arrested Development — plenty more are much sloppier drafts, Parks and Recreation or Seinfeld situations. Community arrives as a recognizable version of itself, and that’s no small feat. It’s funny right away, and it has a decent grasp of what its strengths are even if the characters are works-in-progress. Most importantly, it has a remarkably sure handle on tone: a battle between jaded cynicism and whole-hearted sense of community, and I think you can guess which of those two wins out.

More than anything else, you finish the opening half hour (22 minutes without commercials, as God intended for comedies) wanting to spend more time with these weirdos, to see how they’ll bounce off each other, to watch them become better (and worse) versions of themselves. If that’s not the mark of a great pilot, I don’t know what is.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

More Community reviews

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

7 replies on “Community – Pilot (S01E01)”

Ooh, are you doing a series on Community, Dan? That’s a big undertaking, and I’m here for it! (Love this show.)

I love how they would eventually acknowledge how far Britta’s characterisation drifted from this pilot with an offhanded joke.

JEFF: “I used to think you were smarter than me.”

BRITTA: “Thank you!”

Maybe! I’m glad to know I’d have someone following along. I’ve always wanted to write more about the show, and I’ve been rewatching it with my wife. But yeah, there are a lot of episodes…

Definitely I won’t have each review be as long as this one, as this was sort of an overview in addition to a pilot.

I get that. It’s interesting to get the perspective of someone who was immersed in the context of U.S. sitcoms at the time, I didn’t see any of these until many years later.

Probably my favorite sitcom, which I feel ill at-ease with because it’s everybody’s favorite sitcom (that’s obviously not really true, though it sure seems like a favorite of Internet commentators, rivaled only by 30 Rock, which is also righteous), but it earns the title with such an enormous mass of great episodes (like maybe 50% of the episodes are, honestly, actually great?) and virtually no bad episodes, the closest probably being this very pilot and eventually the sequel to Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. (I kind of understood it a little better on my most recent watch-through, but the problems with season 4 are vastly overstated; I will also say that it’s a testament to how great it is that it survives losing its biggest comedy engine in Pierce when Chase departs/got thrown out, and survives losing Glover way better than it ought to have considering a quarter of the show was doing bits with Pudi.) Benefits from being almost pre-Flanderized (possibly one reason the pilot’s not so hot–Britta and Troy aren’t more-or-less cognitively disabled yet), and getting all the way there so quickly.

Cosigned on modern TV. (At least it afforded us The Good Place, which is awesome, though it managed serialization via sitcom by cheating with its concept.)

I should watch The Office one day I guess because of its cultural importance but when my wife was binging it like a year or two ago everytime I caught a bit of it I 1)never found it funny and 2)found it just absolutely heinous to look at. I also need to watch Parks and Rec eventually.

I would also like us to take a moment to ponder the alternate timeline (not like that) where Joel McHale had Chris Pratt’s career. If that late-era Community episode is anything to go by, McHale does all the time, and he’s right, it is pretty unfair.

Always glad to encounter a fellow Human Being, though as you note there are many of us.

I have a real soft spot this pilot and am probably overrating it a smidge, but I also kind of love how the broad shape of the dynamics and characters are there, though you’re right Troy and especially Britta had the furthest to go. Most of this stuff had to be invented from thin air and a lot of it it is there. Spoilers assuming I get around to writing more about the upcoming episodes as I’d like to, but my favorite version of Community is when it was doing more normal sitcom stuff very cleverly rather than the “concept episode” stuff, though I still quite liked most of those. And agreed its number of bad episodes is vanishingly small. I suspect if I were to get around to rating every episode on the “Is It Good” scale, single digits out of 120-ish will get sub-“Good”.

Season 4 I have pretty complicated feelings about — but I would definitely second your take that its reputation as a singular failure are vastly overplayed. But, I do think it botched a couple of key episodes, and in general the polish of its writing just wasn’t up to the level of the first three seasons, and I do tend to attribute that to Harmon’s absence, though pretty much every sitcom starts running out of gasoline around their fourth season.

Rewatching the show I was surprised to find just how funny Chase is very consistently. I remembered him as more annoying than funny and having bad chemistry with the rest of the cast when I watched in my early 20s, but I was a dumb kid then I guess. He really is an old hand showing the kids how it’s done.

The Office….. would not at all be surprised if it’s not your cup of tea. My claims of it being cinematic come from it having a consistent non-traditional visual style (admittedly naturalistic bordering on “ugly”) with moments of expansion of its visual range for big impact uncommon in other sitcoms. It is certainly well-edited show; at its peak, probably the best-edited sitcom I can recall watching. (For a fun exercise, look up a list of people who directed episodes on The Office: Harold Ramis, Jason Reitman, Amy Heckerling, JJ Abrams, Marc Webb, Jon Favreau, and plenty of others who have made respectable movies before or since. Though I suppose Community had both the Russos and Justin Lin.) But it’s another show I do wonder if I overrate just because I saw it at the perfect time in my life. I also haven’t properly watched it in at least a decade.

I’m not totally sure how I missed this one, given that I like a lot of the other shows from this time, and that I’ve always been a Chase fan. But I’ve never seen an episode. I should probably give it a chance, and understand that it may not charge out of the gate perfectly formed.

That said, while I do respect many of the 2000s sitcoms, in my mind nothing holds a candle to Frasier. Most days I believe it’s the best sitcom ever made. Some days I think it’s the only sitcom ever made. It’s my ultimate comfort watch (and I’d argue it goes well past season 4 before running out of gas), and I just have to try not to think too hard about what it means that my ultimate comfort watch is Frasier.

I’ve never seen Frasier 😅. Always assumed I’d like it. Good to read another endorsement.