Predators and prey

I’m always interested when great directors decide to alienate their audience, and I have to believe that’s the game Luca Guadagnino is playing here. After the Hunt is a movie that practically dares you to hate it, to walk out muttering about how you hate all its characters or resent his “both-sides-ism” commentary. It’s a #MeToo-campus story centered on an accusation of sexual assault. Any sexual assault story is already a tough sit, and After the Hunt embraces a moral ambiguity that is, at best, provocative and, at worst, gross. Unlike the similarly themed Tar, which sharpens the scalpel dissecting the morals of its main character as the movie progresses, After the Hunt seems to delight in muddying its own waters and leaving a thematic mess in its wake.

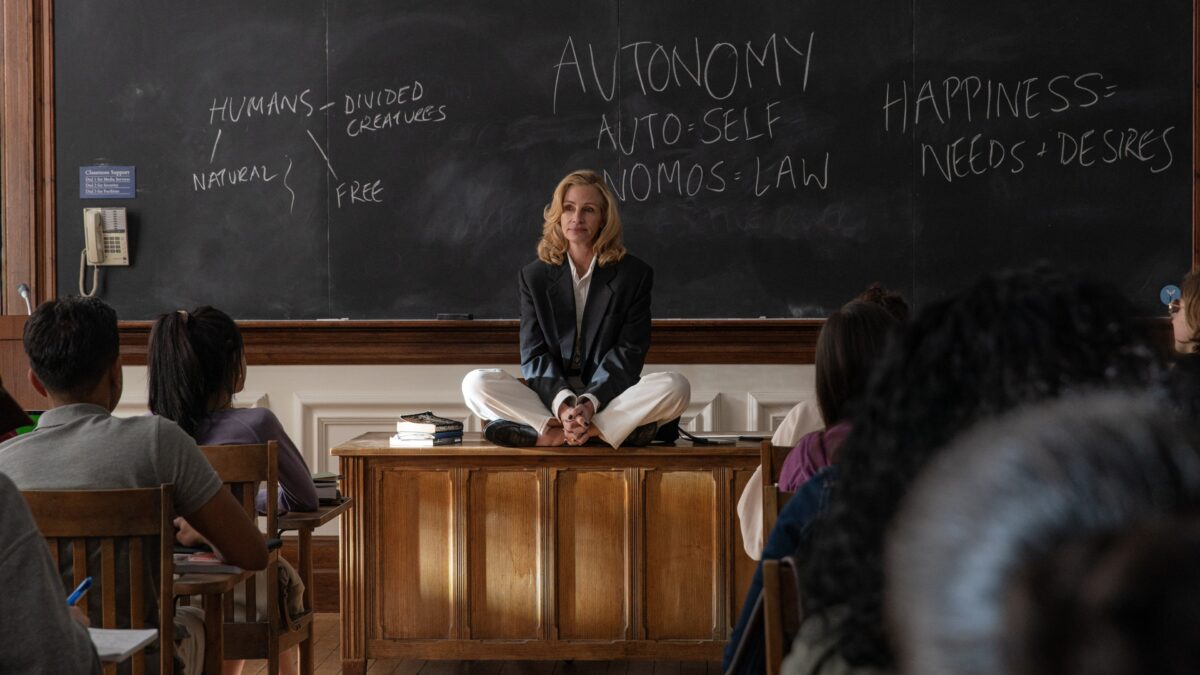

We open the movie at an after-hours party that slides us into Yale academia with Alma Imhoff (Julia Roberts), a beloved philosophy professor who has what every professor secretly wants: a protégé who worships and validates her. That’s Maggie Resnick (Ayo Edebiri), a rising-star grad student who is at once a minority, Black and lesbian, and also someone from a background of wealth and privilege. Maggie’s future is practically gift-wrapped by Alma’s patronage and support of her thesis. Also orbiting Alma is her charismatic colleague and best friend Hank Gibson (Andrew Garfield), another tenure-track big brain. Hank feels threatened by his own normalcy as a cishet white man, and is all the more of a try-hard as compensation. The last major figure in the story is Alma’s husband, Frederik Mendelssohn (Michael Stuhlbarg), a therapist who is jaded about the academic scene and Alma’s peers.

The next day, Maggie approaches Alma and accuses Hank of sexual assault in an encounter after the party, which Hank vehemently denies. And thus, Alma finds herself jammed between her student, her friend, her own ambitions, her marriage that is healthy but always at risk of slipping into turbulence, and a professional ecosystem built on an illusion that everyone can be cheerful collaborators in a big brain-swinging competition.

That’s right, this is a story about how a bystander’s life got uncomfortable when somebody else was assaulted. Yikes. It minimizes the victim’s experience and seriously presents the possibility that the victim is lying or exaggerating her claims, a scenario that studies repeatedly show is vanishingly rare. At face value, After the Hunt reeks of a powerful man hand-wringing about cancel culture.

And so the big surprise for me is that I do not hate After the Hunt, even when I recoiled from what characters were saying or doing, even when I questioned where the camera lingered. In fact, I like this film quite a bit. Guadagnino reeled me in, and I’ve traced that mostly to two main forces.

First: Guadagnino is a sensational director, and I mean that in two senses. He’s a world-class technician with immaculate control — precise camera movements, close-ups that intensify and refract emotions, an indelible sense of rhythm — and he also provokes intense feelings, especially for such a talky, idea-dense script. Material that would play as shrill in lesser hands instead connects as intermittently intimate and explosively evocative. Unlike the sweaty, kinetic Challengers, he doesn’t spice up the staid setting; instead, he makes it peaty like Scotch, still and aromatic except when it burns. It’s sometimes hazy like good buzz, other times blue and cold and nauseating like a hangover headache. That Guadagnino evokes such textural sensations from material like this is the mark of visionary greatness.

Second: the film actually pulls off a layered story about sick institutions without completely collapsing into nihilistic flop sweat — which is more than I can say for Ari Aster’s Eddington. Guadagnino threads a needle between “our systems are irrevocably broken and dehumanizing and “these are still recognizable, complicated souls staggering through them.” On the surface, you’ve got your he-said/she-said accusation and the grinding machinery of public litigation of the alleged crime. And just beneath that is a second, richer story; a nasty little turf war: academics clawing for leverage, crafting public personas and private alliances, gaming the optics of “believe women” while quietly calculating whose career is worth sacrificing.

Then there’s the third story layer, the one Guadagnino mostly tells visually: a twisted, cross-generational love triangle where students and professors covet and resent one another in equal measure. People want to own each other — intellectually, sexually, professionally — and also to smash the codependencies they’ve built. Frederik, Alma’s husband, constantly observes Freudian dynamics and pointing them out to Alma in false playfulness: Isn’t it strange the way Alma and Maggie operate like a couple? Or that horny Hank’s swagger is performative and manicured? Frederik’s disdain for Maggie and Hank is obvious, and a reaction to Alma’s latent attraction to her academic peers (and also a skepticism that Alma would even associate with that crowd).

Guadagnino saves the film’s fourth, deepest layer for late in the film: a revelation from Alma’s past that reframes the whole narrative as a story about how cruelty and abuse don’t move in straight lines. Harm travels in cycles, handed down and reinterpreted and morphing along with unreliable memories and cultural mores. The film seems genuinely interested in how impossible it is to draw a clean arrow labeled “victim” and “villain” when those roles depend, at least partially, upon context, personal viewpoint, and storytelling. (Or do they?)

It’s also no coincidence that all of these academics study philosophy: they’re constantly thinking about how they fit in the world and what it all means. The over-intellectualize their experiences and emotions, to the point that Guadagnino plays it as black comedy: One scene of an on-edge Alma sparring with an undergrad about a philosophical concept is so clearly a mirror of her own issues, and it’s so clear that Alma is aware of this, that I actually laughed at the undergrad’s defeated submission. (It’s, in essence, a much sharper version of the scene of Agnes teaching Lolita in Sorry, Baby.)

Roberts and Garfield are excellent in this: Roberts in particular makes Alma’s self-image crack one hairline fracture at a time, until you realize how much of her intellectual self-superiority is a manifestation of her vanity and fear; she needs to be the smartest in the room, lest she be the smallest. Garfield gives Hank the exact ratio of charm to sleaze where you’d absolutely believe students would go out for drinks with him and regret it later. But Edebiri feels badly miscast. This part gives her very little room to deploy the things she’s good at (e.g., be funny; be charming), and the movie is weirdly uninterested in her inner life. For a story that nominally spins around her accusation, we spend a lot more time watching older colleagues workshop their damage than taking Maggie seriously as a person.

The presentation, as noted, is outstanding. Cinematographer Malik Hassan Sayeed is best known for his work with Spike Lee and for shooting moody but electric videos for Black musicians, including Beyonce’s Lemonade. His pairing with Guadagnino, and for this specific material, is a curveball, as he hadn’t shot a feature film in almost 30 years prior to this. But it’s undoubtedly a success, an intoxicating but well-disciplined visual schema. Meanwhile, the film sounds just as great as it looks, with a terrific, somewhat restrained score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross which sets a perfectly anxious mood. It’s a bit of a shame the critical drubbing means all that good craft work will get ignored come award season.

For all that I like, though, After the Hunt is a deeply flawed movie. Guadagnino’s instincts tilt more cynical than insightful the longer he lingers on doubts about the accusation rather than its fallout. A briefly-teased possibility of a Rashomon-style look at multiple incompatible truths intrigued me; instead, the film mostly sticks to an “objective” vantage point while characters monologue about what they remember. That choice lets the movie posture as bold and ambiguous without actually embodying that ambiguity in its form in any meaningful way (but would these philosophy academics permit the possibility of multiple realities?). When push comes to shove, the naysayers are not wrong: After the Hunt feels like a privileged man moping about accountability, hovering dangerously close to a “what if the cancel mob went too far?” thinkpiece… just with, you know, spectacular lighting and blocking.

But the movie works more than it doesn’t; or, at least, it provokes me in ways I can’t dismiss. There’s a real charge in watching a director as gifted as Guadagnino take a huge, messy swing at the ugliest parts of contemporary academia (mirroring modern society), even if he launches more of a foul ball than a home run, then basks in the boos. After the Hunt wallows in its own moral murk, sometimes irresponsibly. But it captures something queasy and throbbing about how institutions absorb scandal, chew up and spit out the affected, and keep chugging along. I left more uneasy than enlightened, but I also left thinking about it, like truly pondering what I felt and why — which, in this case, might be the best outcome the film could hope for.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

One reply on “After the Hunt (2025)”

First of all, this is a fantastic piece of film criticism. I admire how much you grapple with the movie. Here’s to movies which challenge for better or worse and viewers that rise to the challenge.

For my part, I never got the sense that Luca was trying to alienate. Interesting if true! I think that’s probably something that many established artists toy with at some point. I also didn’t find that this was a movie where the morality was ambiguous, but that the truth was. Often there’s a sense that if we had an omniscient file with the facts in it then we could all get closer to the same moral page. Of course even that’s a little bit of wishful thinking. Rather than both-sides-ism, it feels like the movie just isn’t going to let the audience in on who the hunter and hunted necessarily are and I guess so often neither does life. In fact, it highlights the fact that a lot of times who we go on record as saying is the hunter/hunted is a matter of our own social self-interest which is something well worth reckoning with and how else can it be done than in a story like this? (Maybe in a story not about a sexual assault as I agree it’s always a tough sit).

The movie and your review (another movie like One Battle After Another where the discourse continues to enhance the movie) makes me wonder if there is a perfect justice system. Does it exist?

“World class technician.” The scotch metaphor is choice. Eddington comparisons are apt. “Systems are broken [but] still recognizable souls” Like that you went four layers deep into the story starting at the surface and demonstrating just how much is going on in the writing. “Cruelty and abuse don’t move in straight lines.”

Definitely thought Ayo was better suited to the role than you. Believable.

Re: Eddington again and your point that this is ‘more cynical’ than ‘insightful’…weirdly somehow this seems to be points in favor for me these days. Intellectually honest befuddlement beats the latest panacea. High idealism and transcendent truth aren’t in vogue so maybe nihilism ends up somehow the least pretentious.

Awesome write up