Silence to the animals

Since Hugh Lofting published The Story of Doctor Dolittle in 1920 and kicked off a long-running series of novels, Hollywood has repeatedly tried to adapt the story. And why not? It’s a premise that captures the imagination: A whimsical doctor who can talk with and befriends animals. He becomes their leader. Every kid has dreamed of this scenario.

Here’s the story concocted by Lofting: Doctor John Dolittle is a country physician who starts treating animals, aided by his parrot Polynesia, who teaches him to speak all animal languages. Eventually, his ambitions expand beyond his little English village of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh. He sails for Africa to cure an epidemic among apes. On his journey, he survives a shipwreck, outwits tyrannical tribesmen, adopts a pushmi-pullyu (two-headed llama), evades pirates, and encounters an abundance of diversions and side characters. The books are short and whimsical, featuring themes of naturalism and colonial adventure. Lofting wrote more than a dozen of them, sometimes told through the eyes of young assistant Tommy Stubbins, sometimes from Dolittle himself, but always with a fondness for his growing menagerie.

The filmed adaptations of Doctor Dolittle’s stories have been surprisingly diverse, reflecting various filmmaking trends and approaches, though they have one thing in common: They are almost universally hated. Worst of the decade-type reputation in some cases. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be writing about several Dolittle adaptations, each with its own peculiar (and often doomed) approach to the talking-animal doctor. If this were Kinemalogue, I’d be calling it “Dolittle Week,” or if I were in a snarky mood, “Please Do Less Week.” We also recently dropped an episode on The Goods: A Film Podcast discussing the 1967 version in depth and reviewing various others.

Some problems the adaptations have faced are predictable: For one, Hugh Lofting operated in the Rudyard Kipling space of English authors who loved writing about just how uncivilized the fringes of his monarch’s empire were. This informed many of his stories that involved Dr. Dolittle going out into some wild exotic place, including Africa, and encountering “savages.” Thus, many of his stories are filled with racism and caricature. Plots use white-savior tropes, and Lofting’s prose frequently deploys slurs. The occasional illustrations are the kind you’d find today in a museum exhibit on colonial propaganda. Later editions scrubbed or revised some of the most egregious material, but the DNA remains. Any faithful adaptation of these books will inevitably confront the question of how to handle representation of colonial subjects and indigenous people.

Also, as much as the concept of a kooky vet who can talk with animals makes for an intriguing setup and premise, it does not naturally lead into large-scale narratives. The books themselves are loose and episodic, full of detours and self-contained shenanigans. It’s little surprise to me that the two highest-rated adaptations of Doctor Dolittle (per IMDb) are animated TV shows that support case-of-the-week storytelling. One of these is the 1970 TV series co-created by Looney Tunes great Fritz Freleng and produced by 20th Century Fox. The other is a 1984 Japanese cartoon (with English-language voice acting).

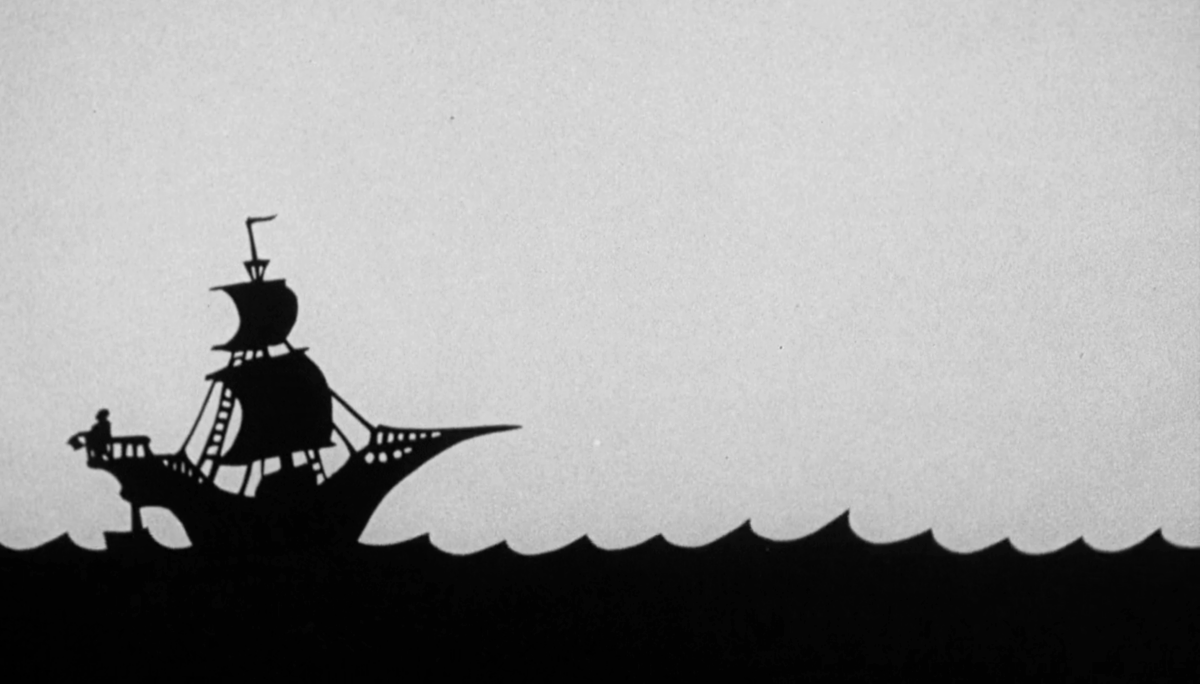

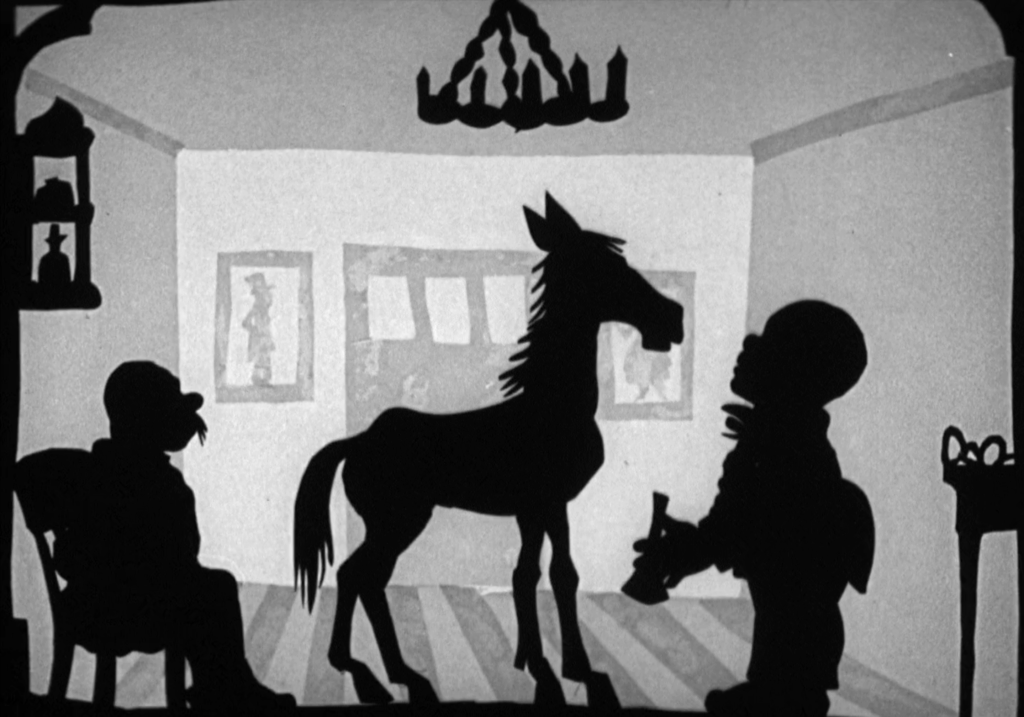

But among filmed adaptations, the most faithful to the source is probably the very first, a piece of silhouette animation by German animator Lotte Reiniger. She is best known as the creator of The Adventures of Prince Achmed from 1926, the earliest surviving animated feature film. That film is a terrific execution of an old-fashioned form of animation: paper-cut silhouettes, often constructed with multiple layers to create a sense of visual shading and depth. Though Prince Achmed is Reiniger’s most famous work, she was a prolific animator: she released nearly 70 films over her career, most of them short-form adaptations of fables, operas, and fairy tales in that silhouette animation style. Her “Dr. Dolittle und seine Tiere” aka “Doctor Dolittle and His Animals” is both a continuation of that approach and a curio within it: an engagement with contemporary material, not Reiniger’s usual subject matter.

I use the word “probably” in describing this Dolittle adaptation in part because it is difficult to say with clarity what it actually is and when it was made. I confess I haven’t managed to get to the bottom of it, as I’ve found conflicting sources online. I’m most inclined to trust the 2017 biography of Reiniger written by Whitney Grace, but I can only read small snippets of it at a time via its Google Books page. (I’m not shelling out $30+ for a copy, and my library does not have it in stock.) The portions I read from the bio suggest that the Dolittle episodes were animated by Reiniger between September 1927 and April 1928, and most movie databases apply a 1928 release date. An article in Animation World Network Magazine by William Moritz about Reiniger’s career lists a premiere of her Dolittle film in Berlin of December 15, 1928, which aligns with this.

Where it gets cloudy is on The Criterion Channel, which has a robust set of Reiniger films and is the only non-bootleg streaming service with this film. Based on the production company logos when streaming from Criterion Channel, their copies of the Dolittle shorts seem to be the ones included as bonus features on the Blu-ray release of The Adventures of Prince Achmed by Milestone Films and Kino Lorber. Oddly, both Criterion and the Milestone/Kino Lorber Blu-ray list the Dolittle film as being from 1923 rather than 1928. I assume Criterion pulled this year from Milestone. I haven’t seen 1923 used as a production or release date anywhere else, but it’s not impossible Reiniger’s Dolittle film existed in some embryonic form then. One piece of evidence that could support this is that the animation here is much simpler than the work in Prince Achmed, which might suggest an earlier stage in Reiniger’s craft. But more likely, the simpler style was a pragmatic and stylistic choice. The Dolittle shorts were aimed at kids, produced much faster and less painstakingly than Prince Achmed was, and not intended for art-house moviegoers. I’m inclined to trust the 1928 release consensus of all sources except Criterion and Milestone on this one.

Then there’s the matter of what the format and duration of the film is. Almost universally, the agreement seems to be that the film is composed of three sequential episodes totaling about 30–35 minutes. I’ve seen no concrete reporting on whether the shorts were initially screened together or shown piecemeal. The only source that defies this 30-35 minute consensus is Moritz in AWN Magazine, who calls “Dr. Dolittle und seine Tiere” a feature-length project totaling 65 minutes. If that’s true, there’s zero evidence of where the missing 30-ish minutes went. Moritz does note that later TV versions (including a TV broadcast with added voiceover) sped up the silent footage, which might explain a few minutes’ difference, but not half the runtime. Did Reiniger animate footage that’s now lost? Or was Moritz simply mistaken? (The latter seems likely.) Interestingly, Reiniger herself suggested in her book Shadow Puppets, Shadow Theatres, and Shadow Film that Dolittle’s stories were best suited to 10–15 minute silhouette plays aimed at children. That would seem to argue for short-form episodes.

The last matter of confusion is whether the film is “unfinished.” The third and final episode concludes at the end of Lofting’s first book, The Story of Doctor Dolittle, so it seems like a natural stopping point. Grace’s biography of Reiniger claims the shorts end on a “cliffhanger,” but that’s not the version I watched. (Unless you count Dolittle wistfully looking off into a sunset as a cliffhanger.) A German animation fan site says Reiniger never got the funding to continue her vision of expanding her adaptation of the Dolittle novels, which makes sense to me, but that claim doesn’t appear in the Grace excerpts I could find. My read: Reiniger, who knew Lofting personally according to the linked site, adapted the first book in full, and had ambitions to do more but was ultimately stymied by the usual suspects: money and time. That’s not so much an “unfinished” film as an “unrealized sequel” situation.

Regardless, it seems that the Düsseldorf Film Museum has copies of the films, and probably answers to some of the questions I posed above. The museum catalog, accessible online, lists numerous entries related to the film, but even aside the language barrier it’s hard to parse the metadata to get any concrete answers.

So I watched the first and third episodes on Criterion Channel, but the streaming service is missing the second episode without any explanation. Maybe that’s an intentional omission: the second short is the one that contains the most overtly racist imagery, portraying a group of indigenous African “cannibals” as grotesque Black savage caricatures who imprison Dolittle and his animals. But YouTube currently hosts the TV edit of the second episode (sans intertitles). Thus, as far as I can tell, I’ve seen the entirety of Reiniger’s adaptation in some form.

With all that background: What’s actually here? Reiniger’s film is a charming and visually clever adaptation of the Doctor Dolittle origin story, rendered in Reiniger’s trademark style. We meet the rotund Doctor in Puddleby, see him learn to speak animal languages, watch him set sail for Africa with his menagerie, and follow him through a series of gentle misadventures: a trip to Africa to aid some sick monkeys, getting captured by “cannibals,” and plucking a thorn from the foot of a lion. No pushmi-pullyu, sadly. The film wraps up with Dolittle in Africa having helped some animals, smiling serenely as the camera fades: mission accomplished.

The animation is, unsurprisingly, delightful. Reiniger’s silhouettes remain expressive and fluid, and her ability to conjure action and emotion from simple shapes is as well-formed here as in Prince Achmed. That said, the production feels pared down. Gone are the color tints and suggestion of depth with layered silhouette arrangements; many scenes play out in a single, flat silhouette against a white background. It fits the lighter, less mythic tone of the Dolittle material, but I was hoping for a bit more visual flourish.

But one major piece is missing: voice. Maybe it’s because this is a silent film, but this is the only adaptation I’ve seen that doesn’t make a point of dramatizing Dolittle’s ability to communicate with animals. In the books, and nearly every other adaptation, this is the main point, of course. It’s the source of the comedy, wonder, and chaos. Here, we just see him nodding and gesturing at his loyal animal companions, and they respond in kind. The concept is implied, I suppose, but the absence of any communication makes the magic a bit more abstract. To be fair, Dolittle’s ability to understand animals is nonverbal in the source books, and rendered as such in the 1967 adaptation (whereas most later adaptations use voiceover when animals “talk”). But Dolittle conversing with animals in one form or another is always there, except for this one.

So here it is: the first and most attractive adaptation of Doctor Dolittle. It’s brisk and hews closely to the core arc of Lofting’s novel (racist ickiness and all). Watching it, it’s easy to detect ideas explored in the (too) many future adaptations, a barely extant little sprout of a film. It’s a bit of a shame it’s slipped through the fingers of film history. Reiniger’s film deserves to be remembered not only as a historical artifact, but as a charming piece of animation.

But seen today, Lotte Reiniger’s Dr. Dolittle und seine Tiere is both too slight and too marred with the baggage of the story to count as a hidden gem. Even still, there’s a case to be made it’s the best theatrically released or feature length adaptation of Doctor Dolittle ever produced. (I have another pick, but this one is probably second place for me.) That’s not a high bar, but that’s the nature of Dolittle adaptations.

Is It Good?

Nearly Good (4/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.