Street fighting women

Fear Street: 1994 worked in spite of being tethered to an overarching mythos. Fear Street: 1978 takes it a step further. It works, in part, because of this. Given my hesitation with quantity-over-quality stories, I would have guessed the opposite, but this middle chapter manages to be both a satisfying standalone slasher and a smarter, more engaging film for being part two of a trilogy.

Much like the trilogy opener, Fear Street: 1978 offers a slick production and some surprisingly thoughtful teen drama. The scares are solid, the plotting zippy, and the characters, once again, have more emotional definition than this genre often bothers with. You care at least a smidge when they die, which is bad news for your nerves but good news for the story. Director Leigh Janiak (returning from 1994) stages the chaos with a confident eye that makes you forget this ended up as a COVID streaming dump. It’s a movie that would’ve played well with a crowd and on a big screen.

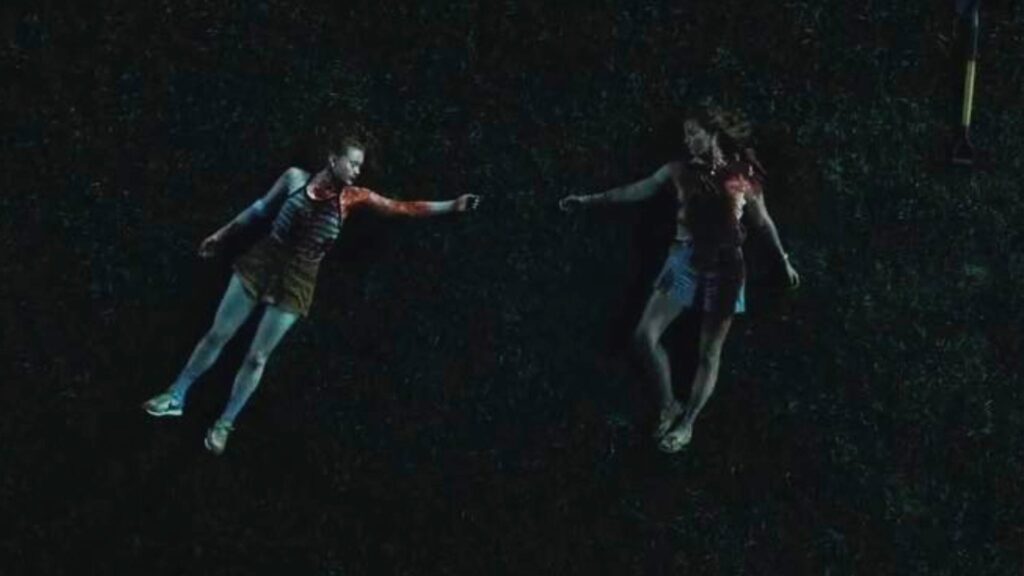

The story opens with a flashback to 1978 at Camp Nightwing, the night of a notorious massacre. The tale is recounted by the sole survivor of the event, C. Berman (Gillian Jacobs). Two estranged sisters, rebellious outcast Ziggy Berman (Sadie Sink) and rule-abiding counselor Cindy Berman (Emily Rudd), are trying to get along with a group of campers split between bum-luck Shadyside kids and privileged Sunnyvale kids. When a counselor, Cindy’s beau Tommy (McCabe Slye) has a psychotic breakdown (but really possessed by an evil spirit) and goes on a bloody axe-wielding rampage, the camp descends into chaos. Bodies pile up and secrets buried beneath the campgrounds reveal the camp’s connection to the curse introduced in the first Fear Street chapter. Cindy and Ziggy are forced to overcome their own fractured relationship to try to survive the murder spree.

One of the smartest tricks in Fear Street: 1978 is how it folds the larger trilogy lore into its structure. We, the audience, know the curse is real, and understand some of its rules. For example, we know what a bloody shirt means (you’re about to get hunted), and that the possession can spread. The film’s teens, all summer campers, know none of this. Janiak uses this dramatic irony to crank the tension. Every familiar name, every glimpse of a Fier witch totem, every lurking shadow carries more portent because of the violence we saw in Fear Street: 1994. Even the casting choices deepen the game: Kiana Madeira (Deena from Fear Street: 1994) appears briefly in a surprise double role in the closing minutes as Sarah Fier herself in a flashback setting up Part 3, 1666. And the film stretches out a genuinely engaging “who survives?” mystery with C. Berman’s identity, slowly teasing whether the traumatized adult we met in 1994 is Ziggy, the bullied misanthrope, or Cindy, the more traditional final girl.

The film also mirrors and remixes some storytelling from Fear Street: 1994. Both have a theme of bullying — though in 1978 it’s cloaked in the ritual of hazing and mean-girl summer camp hierarchy rather than high school hormone aggression. The film depicts some understated lesbian attraction, no longer tentative acceptance but deeply repressed longing. We also spend time in both with Nick Goode (Ashley Zukerman in 1994), future Sheriff Buzzkill, here revealed as a floppy-haired nerd (Ted Sutherland) with a sensitive side and something resembling a conscience. It sets up a possible about-face for the grown-up character in part 3. (Another mirror to Part 1 is that Fear Street: 1978 is about 20 minutes too long; no slasher should be a stone’s throw from two hours. But, maybe because of the busier story, I admit I felt the extended runtime a little bit less than I did in Fear Street: 1994.)

Except for a quick frame story in 1994 and a closing teaser set in 1666, we spend the entire runtime in 1978, which slasher-heads will recall as an important year for the genre: it’s the year that John Carpenter’s Halloween essentially invented slashers. And yet Fear Street: 1978 is much more referential (and reverential) to a slasher from two years later: Friday the 13th. That gory teen classic is one Fear Street: 1978 resembles not just in setting (minus a lake), but in structure: sex, sudden carnage, and obliviousness by most campers until it’s too late. The film also includes a couple of obvious references to Texas Chain Saw Massacre from 1974; a villain at one point wraps some leather around his face.

And yet Fear Street: 1978 isn’t just a Friday tribute. It borrows the setup but not the “deadfuck” subtext. Horny teens may die, but they don’t die because they’re horny. The story is still operating in supernatural thriller spook-em-up territory. Also, unlike Crystal Lake, Camp Nightwing actually has kids running around, which ups the squirm factor significantly when the axe starts swinging towards prepubescent necks. The result is a film a touch meaner than Fear Street: 1994, but not worse off for it.

The performances are again decent enough. Sadie Sink (of Stranger Things fame to some) makes a vivid impression as Ziggy, carrying wounds both literal and social. Emily Rudd is fine, too, as Cindy, giving the clean-cut foil to Ziggy some quiet desperation as she scrubs away her past with forced cheer. The best supporting turn comes from Ryan Simpkins as Alice, the punk burnout who turns out to have both a soul and a survival instinct, plus some sparks with her former friend Cindy (a parallel to Deena and Sam in Fear Street: 1994). Nobody here is quite as fun as Fred Hechinger’s Simon from 1994, but there’s depth and pathos that compensates.

The slasher mechanics continue to hum well. The stalking and jump scares are strong, growing in suspense across the runtime. None of the scenes is as well-constructed as the supermarket climax in 1994, but a few sequences get close. Cindy and Alice’s cave exploration is a torch-lit highlight: suspenseful and a bit grody.

I also continue to love the series’ over-the-top period flavor. It isn’t subtle — bell bottoms, joint-passing, and radio rock needle drops abound — but, like in Fear Street: 1994, that’s the fun. (I am a little skeptical this will hold up in our upcoming 1666 sojourn.) The washed-out colors evoke the era the same way Fear Street: 1994‘s neon mall lights did its own. The texture has a tactile grubbiness to it all: cheap camp furniture, form-fitting fashion, and sweaty cots. “Carry On Wayward Son” (a banger) rips not once but twice.

Fear Street: 1994 weaponized high school angst and late Gen-X/early millennial nostalgia of grunge and mall culture. 1978 sharpens its blade on economic hopelessness and that druggy no-man’s-land between the Summer of Love and Ronald Reagan. The flavor isn’t as appealing to me, and the overall exercise is still a bit too frothy and light to enter any horror pantheon. But the storytelling in 1978 is a smarter and bolder than its predecessor, and I’d honestly give it a slight edge over 1994. Bring on 1666.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “Fear Street: 1978 (Part Two) (2021)”

Not going to lie, this is my favourite part of the series because it actually breaks my heart – Slasher films belong to one of my least favourite horror picture because they generally use and abuse characters with complete heartlessness, but this film actually feels something for the poor souls who make up it’s butcher’s bill and actively encourages us to do them same (Even for the poor bloody Slasher).

Glad you like this one too. Yeah, I didn’t really mention the “twist” factor of having the murderer be a camper we’ve already come to like but it’s cleverly done and, like you said, kind of sad.

Interesting: it might be a case of middle-child syndrome, but this is the entry in the Fear Street trilogy I barely remember at all. The elements that enliven parts 1 and 3 – the queerness, the structural chicanery, the bread-slicer kill – seemed absent to me here.

Then again, I don’t like the Friday the 13th movies, not even the “good” ones, so take my opinion with a grain of salt.

Seems reasonable. This one is definitely more devoted to filling in a pre-established story and paying tribute and/or messing with the Fridays that I could see it leaving less of an impression.