My words fly up, my thoughts remain below

I regularly suffer from impostor syndrome. (In fact, I feel like a little bit of a fraud even claiming I suffer from “impostor syndrome” because it suggests some objective level of credibility and success.) But one area in which I really am an impostor, a failure as a graduate of a nationally-ranked liberal arts university, is that I have never seen nor read Hamlet. I know some of the basics — ghost of a dad, murderous uncle, holding a skull, “to thine own self be true,” all that jazz — but not how they come together into a complete narrative. I am a total Hamlet neophyte, a Danish virgin.

In an upcoming episode of The Goods: A Film Podcast, we will be discussing the 1990 adaptation of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, and I assumed I won’t get nearly as much out of that film without some strong footing with The Bard’s original, so I decided to finally take the plunge. I figured the classically revered, Best Picture-winning adaptation was a good place to start. It took me past the halfway mark of neither meeting a character named Rosencrantz nor Guildenstern to Google and realize that director-adapter-star Laurence Olivier excised them (along with half of the play’s text) for his film. Whoops. Guess I’ll be watching Kenneth Branagh’s four hour behemoth, too.

Anyways, this review is going to sound a little bit like “have you guys heard of this tasty dessert called ice cream?” But I’m going to allow myself some high level Hamlet reactions. For starters, I was much more moved by it than I expected. It’s a terrific blend of intrigue and emotion, with an ending that feels at once inevitable and easily avoided had its characters acted with a bit more wit, wisdom, and generosity. It earns that “Shakespearean” labeled.

I was deeply struck how much this is a coming-of-age story, which is not typically how I see the play characterized. Maybe I’m just filtering it through the hundreds of teen movies and YA novels I’ve consumed in my life, but so many of the themes and beats of the genre are here. Hamlet’s teen angst and urges upend the complex adult political and social world, heightening every conflict and relationship. There’s first love and first heartbreak; childhood friends on different paths; mommy issues and “you’re not my real dad!” Hamlet performatively adopting the persona of “crazy bad-boy” and acting it out to the point where it’s indistinguishable from his real identity is essentially the plot of Mean Girls.

There’s such appealing ambivalence and layers built into the characterization and writing that it’s easy to imagine the play staged with wildly different tones that still feel compatible with the text. For example, Polonius (Felix Aylmer) in this iteration is doddering and hapless; he may just as well be a conniving Machiavellian or alternately the sympathetic voice of reason depending on the staging and performance.

And yet aspects of the story just didn’t click for me, and it’s going to take a viewing of a few different adaptations before I decide if my hangups are with the adaptation or the source. The entire final third of the story is a bit mealy and overcooked: Hamlet’s abrupt departure then return is rushed and confusing. I suppose it’s a pretext for a time jump and a resetting of the dynamics of the court, but it’s quite the jarring lurch in the story.

I also, as I frequently do with his work, find Shakespeare’s depiction of the supernatural frustratingly literal: I like the idea of the specter of the dead king hanging like a shadow over the palace intrigue as well as Hamlet specifically. Maybe it’s the standards of Shakespeare’s pre-psychology, pre-Romantic, pre-Gothic times, or maybe it’s just the necessity of writing for a physical stage. But a physical spirit tromping around in armor speaking coherently just seems kind of silly to me. Even if the ghost had simply appeared to Hamlet and no one else, it might have remained a tantalizing ambiguity on Hamlet’s degrading mental state vs. haunted grounds. (Though if only Hamlet had seen the ghost, it would deprive us of the perfect mood-setting opening scene.) We’ll see how I feel on this matter once I’ve watched a couple different adaptations.

As for the adaptation itself: This Hamlet is overall quite handsome and inviting. Olivier’s performance in the lead is one of those sterling benchmarks against which others of this ilk are compared. Sure enough, he absolutely invigorates every scene with sheer charisma. It’s easy to imagine Olivier as a stage star, drawing the eyes of every theater-goer, nailing every enunciation and gesture and emotional beat. And yet I can’t help but feel like his choices aren’t the ones I’d make for the character: He’s overconfident and a bit chilly. None of the coming-of-age angst comes out.

The rest of the cast is largely wasted. I like Aylmer’s Polonius quite a bit, but that’s about the only other performance I’ll call out positively. On the negative side, Jean Simmons is catastrophically vacant as Ophelia — there’s so much subtext that she’s the kind of young woman who would throw your life off-kilter, not some drifting pretty-girl. Terence Morgan as Laertes is fine for the first two thirds of the story, but by the time he’s scheming Hamlet’s death, his mooring on the character is gone.

As a visual object, the film is wonderful to spend time with, yet weirdly empty. Olivier and his team — notably cinematographer Desmond Dickinson — have very carefully built abstract palace spaces and a camera that floats precisely in long takes with shifting focus: very technically sophisticated and pleasing (and very clearly inspired by Orson Welles). The lighting is terrific.

Yet it’s as if they’ve mastered the syntax of cinema but none of the language: the film still feels stagey and bound to a proscenium. In other words, much of the visual work of the film is showy without offering much substance: the terrific camera work mostly moves us around settings and scenarios without probing us deeper into the minds or hearts of the characters.

I also gather from reading a few reviews that this telling is a bit more Freudian than your typical Hamlet. It can’t be normal that Gertrude is played by an actress a decade younger than Hamlet’s actor, and Eileen Herlie has a sensuous screen presence. But I also have trouble imagining the story without at least a little bit of an Oedipal thrust to it, even if Olivier takes his goo goo eyes for his momma a little bit far.

Overall, I was enraptured by the film, and I’m very excited to see some more modern takes on the classic play. Hot take: Hamlet is good.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

3 replies on “Hamlet (1948)”

I admit that when it comes to Shakespeare, I’m very much on the Full-Bore Witchery side of the equation (At least in principle): one feels it adds to the mythic aura and sheer pageantry of these pieces.

Not that I object to some lucid psychological studies in my Shakespeare, but one likes a bit of spice to go with the meat!

(On a less savoury note, if you’re looking for a slightly less Epic Hamlet, you could do worse than to try Mr Zeferelli’s version, though that would mean you had to take Mr Mel Gibson along with Ms. Glenn Close and Ms. Helena Bonham-Carter … also, I’m not sure if the full Rozencratz and Guildenstern experience is to be had in that particular adaptation).

“I am [[…]] a Danish virgin.”

Well, I don’t know about that, but you *are* a Virginian Dan.

I would be able to overlook Olivier’s pronounced age, or at least I wouldn’t be so against it, if he didn’t also play Hamlet so mid-40s, stern and in-control, like he basically is his own dad already. (It doesn’t help that he’s not de-stagifying it much.) It’s such a disaster of a performance. I’ve seen Olivier be good (That Hamilton Woman, Marathon Man way out on the other side of his film career) but I dunno, I’ve seen him be terrible too (this, Wuthering Heights).

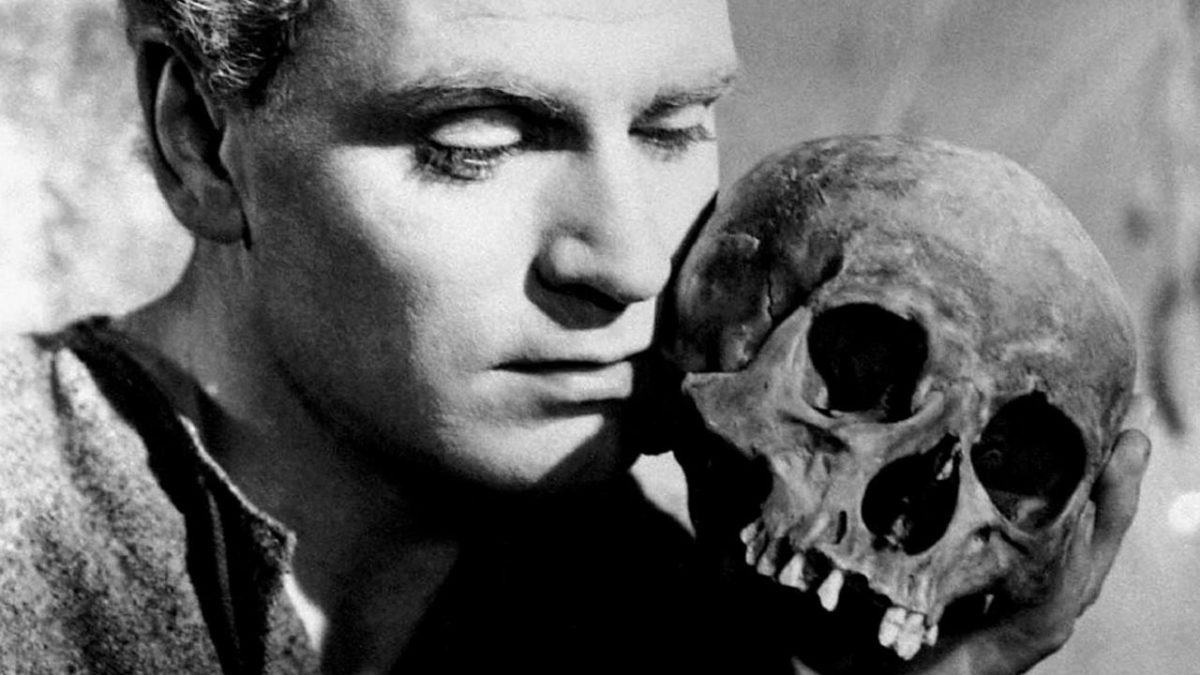

I’ll always find it ironic that the chief recommendation of his Hamlet is its visual construction. Yorick’s “cameo” is such a highlight, probably my favorite image in any Shakespeare movie I’ve ever seen.