To weep or not to weep

The world needs weepies. Crying is a pressure-release valve for the soul, especially when the thing you’re grieving is a story performed by attractive people on the silver screen. So I’m not begrudging Hamnet its ambitions of eliciting my sobs. I consented to the emotional mugging.

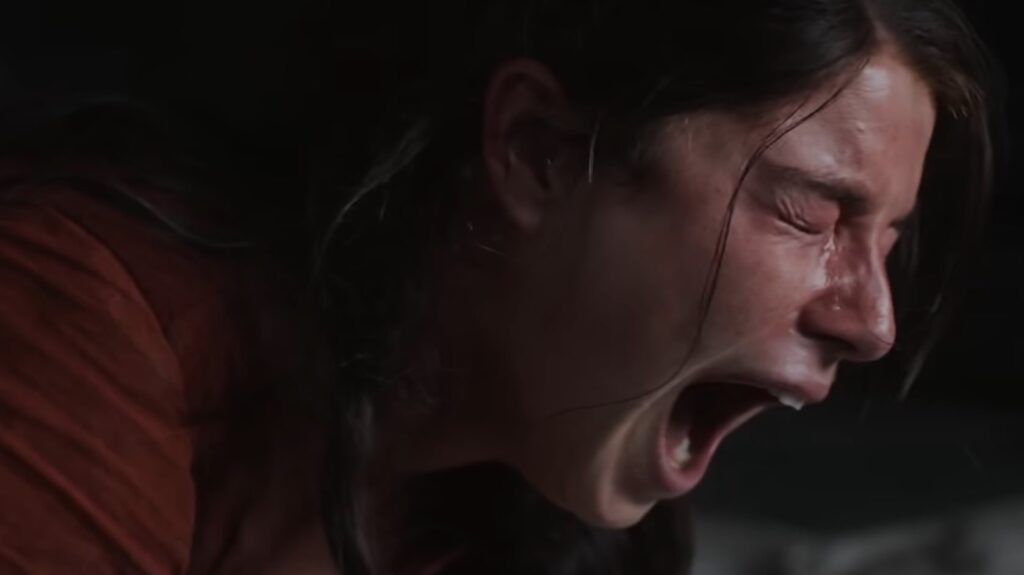

And sometimes, the movie absolutely lands the punch in swings with. William Shakespeare (Paul Mescal) telling his son Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) to be strong and brave in what is so clearly their last shared moment is the kind of scene that bypasses my critical defenses and goes straight for the ribs (at least for me, an emotionally fragile dad). There are a couple other moments with that same gut-level power… though, they tended not to be the moments that scream at you, which is notable, because Hamnet, or rather Agnes Shakespeare (Jessie Buckley), does scream at you, literally, several times.

What holds the film together, sometimes more than the writing or direction, is Łukasz Żal’s cinematography. It’s rich and aching, a steady hand on the mood’s tiller. Woodlight slants through branches and windows, candle flames tremble like they’re trying just as hard not to cry as the audience, and the whole first half in particular has a vibe of romantic fantasy, almost folk horror: rural mysticism where nature radiates uncontrollable power.

That unadorned spirituality is perhaps the film’s best thematic idea: Agnes’s belief in the spirit world, in unseen threads between people, in a presence that can be felt even when it can’t be proven, lining up with mundane tragedy. When the film is thrumming, it treats that worldview as a kind of practical magic full of forces of fate and destiny; later, when she’s left behind that world and embraced civilized motherhood, it gives some shape to everything else that happens.

The problem is that director Chloe Zhao keeps mistaking stillness for depth. Hamnet is meticulous, but it doesn’t always fill that space with actual complexity of character or emotion. Zhao indisputably has a knack for crafting a gorgeous visual mood, one that’s too steady and humorless and glum, but doesn’t translate it into the otherworldly resonance it’s aiming for. It has beautiful frames but a nagging hunger for a real voice — something stranger, funnier, angrier… anything, really; though when it does take a few swings in the final act, they mostly miss, so maybe this aching void was the right call.

Buckley, for her part, is quite good at what the movie asks of her, which is basically: (1) gloomy reticence, and (2) howling agony. That’s not really a knock on her performance, though it also doesn’t really justify the all-but-guaranteed golden statuette she’ll be getting in a month or two. (It’s not apples-to-apples, but why couldn’t Danielle Deadwyler’s less showy but more complex work in my The Woman in the Window get this recognition? …I guess the “less showy” part of the question answers it.) Hamnet certainly hands Buckley a enough Oscar-reel moments to run her campaign, then gives us a few more for good measure. Mescal, meanwhile, is stranded in a vastly underwritten version of Billy Shakespeare (as LFO called him): a husband, a father, a man who leaves, a troubled creative, and yet none of those in any interesting way. Mescal wrings a few moments of depth or charm from the character, but it’s such a dull portrait overall.

Where the movie really loses me, though, is in depicting the creation of Shakespeare’s plays; you know, the ostensible reason for telling this specific story in the first place. Hamnet seems to think Hamlet is a sad play about death, and no more than that. No “tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral… poem unlimited.” The scene where Mescal’s William weeps as he improvises “to be or not to be” on the edge of a pier, staring out at the ocean, is perhaps the most confidently idiotic scene in any movie this year. Genuinely, unintentionally hilarious stuff.

The late-film bafflement continues in the Hamnet’s final sequence, in which Agnes attends the premiere of Hamlet and reacts as if she’s never encountered the concept of a “play” before, despite being married to a fella named William Shakespeare for a decade, and during his most productive period. Did she never ask what all that stuff he was writing was? I can forgive biopics a lot of historical invention if it means a good story, but this edges into preposterous. The idea that she’s seeing through Hamlet’s story and witnessing Shakespeare’s pain is just ridiculous. This is supposed to be the emotional payoff of Hamnet, and it’s completely misbegotten.

So why do I land anywhere near “positive” (and please note that I am liable to change my mind on the matter)? Because it still has a textural richness, especially in the visuals. Żal and Zhao’s images keep the tone from collapsing into pure misery soup. Because Buckley and Mescal can still make a blunt instrument feel like it’s cutting true. Because sometimes I wanna cry. And because when I imagine Hamnet winning any of the Oscars it’s circling, I don’t feel rage, just a kind of weary acceptance. Which, in 2026, is apparently the bar for a passing grade.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “Hamnet (2025)”

Yeah, but Hamlet and Hamnet are only off by one consonant. So are Hamlet and Amleth, but never you mind.

I’ll conceivably watch this eventually, and one reason is an extreme curiosity as to why they’d make a movie based on the highly-disfavored idea that grief over Hamnet powered the writing of Hamlet. I mean, if you’re gonna just invent stuff, Titus Andronicus predates Hamnet’s death iirc, but feels like it could be more readily twisted into a metaphor about artists exploiting real emotions as grist for art.

More than anything, the whole affair just makes me want to watch Upstart Crow again.

I find room in my heart for both (and SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE, not to mention ALL IS TRUE besides) but HAMNET is definitely

in the ‘trusty, well-beloved servant’ and not ‘heart’s darling’ category.

Also, some Serious ‘lead character costuming’ going on: Master Will, where is thy hat?!?

One thing I appreciate about this film is that it’s perfectly happy to put across that it’s messy and occasionally-tragic but loving central lovers can be right ***** in their own right: Mrs (Agnes) Shakespeare is consistently rude (and only once hilariously so, at the play) and her treatment of her stepmother strikes me as particularly contemptible (Whether or not this is the case in novel, the second Mrs Hathaway consistently comes across as somebody who never stood a chance with her stepdaughter, rather than somebody who never made the effort): meanwhile Master Will is a hot mess at most times, Bless him and curse him for being a somewhat self-involved neurotic.

Honestly, it’s not my favourite Stupid Sexy Shakespeare film, but it’s a worthy addition to the canon (I spare you my thoughts on Master Will’s attempt at Father Hamlet and will most assuredly sore you my active contempt & dislike for Shakespeare’s Prince of Denmark as I understand him*).

*Would still love to see a HAMLET that went full Film Noir though.

“Agnes attends the premiere of Hamlet and act as though she’s never encountered the concept of a play before.”

YES, thank you. I couldn’t believe this was happening in the moment. I said to myself, wait are they really going to have her interrupt this whole performance because she doesn’t understand what’s going on? Is she 7 years old? And that’s damn near what happened. Yet I didn’t see any critical review bump on that, and in fact many of them highlighted the ending as their favorite part of the movie.

That, combined with the fact that I don’t think there’s actually any evidence of a connection between the writing of Hamlet and the death of the son, or that it helped him and his wife get closure, helped save their relationship, etc, makes this movie seem rather silly to me.

The lady friend liked it a lot though (and judging from the critical response, she’s not alone). And you know Buckley is going to win for it. I think a lot of moviegoers today find something refreshing in a heartfelt story with good actors that transports you to a different world without any talking pets or CGI-light-battle-orgy-climaxes, and I can understand that.