"Why we still got monkeys?"

This July, we will mark a century since the Scopes Trial of 1925, aka “The Monkey Trial.”What better way to celebrate than watch a movie about it? Even if we weren’t on the verge of the centennial milestone, Stanley Kramer’s Inherit the Wind would be a provocative and timely watch. It’s a sadly enduring look at the intersection between intellectual freedom, civic courage, and public spectacle that has come to define American culture wars.

Though set in the 1920s and written in the ideological aftershocks of McCarthyism, Inherit the Wind is frighteningly timely. In an era where political discourse is increasingly vitriolic and performative, rife with anti-intellectualism and close-mindedness in even the highest offices of the American government, the film is less of a time capsule and more like an urgent dispatch from a long-running cultural fault line. It’s a courtroom drama, but also a heated parable about what happens when dogmatic belief refuses to find a happy coexistence with reason.

The story is a roman-à-clef, lightly fictionalizing the Scopes Trial but sticking rather close to documented history. The names are changed, but many of the logistics of the courtroom sparring are lifted, if not verbatim, then in spirit, from the actual record.

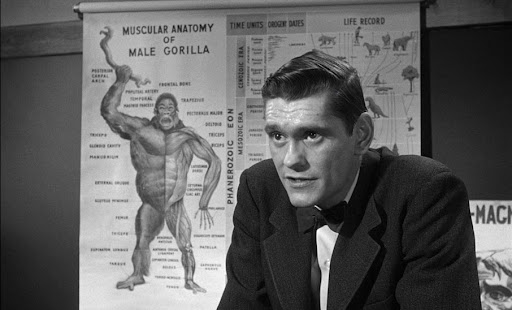

It kicks off with an act of civil disobedience: a small-town science teacher, Bertram Cates (Dick York), a stand-in for John Scopes, is arrested for teaching Darwin’s Descent of Man in violation of state law. In truth, Scopes taught from a state-approved textbook rather than directly from Darwin, and his arrest was pre-arranged as a publicity stunt. But the version here makes for nice drama — a small act of defiance setting off an avalanche. What follows is not just a trial but a traveling circus, complete with marching bands, fire-and-brimstone sermons, and a media frenzy that helped reshape the American justice system into a national spectacle. This was the first trial ever live-broadcast on radio. The affair transforms the fictional town of Hillsboro, Tennessee (in real life, Dayton) into a sweaty arena for national debate.

At the center of the storm are two legal titans: defense attorney Henry Drummond (Spencer Tracy), playing the Clarence Darrow role as a blend of weary and stalwart, and prosecuting orator Matthew Harrison Brady (Fredric March), a firebrand populist with a Bible in one hand and a campaign stump in the other. Brady is, of course, the complicated historical figure William Jennings Bryan, many-time presidential candidate whose intense but varied policy positions are baffling in the modern political landscape: He was a Bible-literal creationist and a die-hard union labor advocate, a progressive by reputation who nonetheless favored prohibition and served as a face for Christian fundamentalism. E.K. Hornbeck (Gene Kelly, trading tap shoes for a typewriter), a sardonic journalist modeled on Baltimore columnist H. L. Mencken, chronicles Brady and Drummond’s verbal duels. The courtroom becomes their battleground — not just for Cates’ fate (in fact, in spite of Cates’ pre-ordained conviction) but for the soul of religion and reason in public discourse.

The film is less procedural than your typical courtroom drama and more polemical: The script is is more about monologues and flowery exchanges than it is motions and evidence. But this is in line with history: The Scopes trial itself was a kind of civic theater, more about public narrative than jurisprudence. Kramer leans into that with heightened, near-theatrical dialogue that aligns with the famous director and producer’s reputation as a preachy late-studio era stalwart. But the film is still quite riveting.

Kramer’s filmmaking is clean and a bit theatrical, never inert. Ernest Laszlo’s Oscar-nominated black-and-white cinematography gives the film a richness, radiating Tennessee summer heat. The production is outstanding: Faces glisten with sweat and every wide shot bustles with commotion bordering on claustrophobia of the packed small-town courtroom. The blocking is noticeably well-designed, giving the talky scenes some dynamic energy. Although Kramer might be best remembered for his “message movies,” Inherit the Wind reminds us that such specimens need not be poorly made.

Among the most charged choices Kramer makes is including imagery that evokes Jim Crow South racial tension, even though race is not a factor in the narrative. A night scene involving a torch-wielding mob clamoring for Cates’s execution reads like a chilling echo of mid-century terror against Black people. Kramer added these images to infuse danger into the conflict that audiences would recognize in 1960, a time when headlines about lynchings were still common. The use of this imagery also ties moral hypocrisy in the name of Christian values of the Scopes trial to the contemporary culture struggles that America was facing.

Even with its sterling and sometimes bold production, Inherit the Wind belongs centrally to its cast. March is magnetic, bombastic with hints of brittleness. His Brady is a fading lion puffing himself up with moral certainty until he unravels. The actor (surprisingly not nominated for any awards) brings humanity to a role that could’ve easily tipped into caricature. Tracy, by contrast, is all gravelly understatement. It’s an easier role than March’s as the plucky underdog, but Spencer really carries it. And then there’s Gene Kelly, relishing the chance to play acidic and quippy against the heavy backdrop. He adds just the right amount of dark humor and wit to the proceedings.

The central tussle between Drummond and Brady operates in a register that borders on Shakespearean. Their dynamic isn’t just adversarial, it’s elegiac. Old friends gone down different paths become ideological combatants, wrestling over the soul of an evolving and industrializing nation. This culminates in a truly outrageous scene that is, against all odds, based on history rather than Hollywood creation: Drummond calls Brady as a witness to defend the Bible itself. God is, almost literally, on trial. What starts as a theological cross-examination dissolves into something more poignant: man clinging to doctrine as it crumbles around him, betrayed not by his beliefs but by his unwillingness to let them grow. Brady’s sudden death (only slightly more rushed than Bryan’s real-life demise five days after the trial ended) is a symbol of a hopeful vision: An America that lets go of a worldview constrained by fundamentalism and hatred, instead offering a broader embrace to progress and reason. (About that…)

Not everything in Inherit the Wind lands. The romantic subplot between Cates and Rachel Brown (Donna Anderson) is a bit of Hollywood fluff. It plays like an obligatory studio note: soften the edges, add a dame. There’s also a flatness to the soundtrack given that Kramer’s efforts to use gospel and vocal music to evoke southern flavor. I hope you like “The Battle Hymn of the Republic!” And Inherit the Wind is undeniably a film you need to be in a certain mood for — if you’re hoping for something narratively dynamic, it will definitely drag.

Still, these are minor problems and quirks in a film that manages to be thoughtful without being boring, rich with ideas and righteous fervor. For a story that’s “dramatized,” it sticks remarkably close to the spirit of what happened — and it sticks even closer to why it mattered. That’s really what makes the movie worth watching. For all its stately oration and overt message-making, Inherit the Wind is evergreen. The original trial took place 100 years ago and the play just 30 years later, but the conflict and rhetoric haven’t aged. I guess it’s baked into the American DNA, perhaps dating back to our Puritanical pilgrim roots. Every decade, every damn day it seems, there are major surges of anti-intellectualism masquerading as religious virtue and conservative cultural resilience. So Inherit the Wind might look like a period piece, but what it’s really dramatizing is a perennial truth: the right to think and embrace reason is always up for debate and never something we should take for granted.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

2 replies on “Inherit the Wind (1960)”

I still remember watching this, thinking “oh, this part must be made up” when Brady ended up on the stand, and then being amazed to read about it afterwards.

Also, I’ve become a fan of Mencken’s writing in the years since I saw the film, but had never thought to connect him with the Kelly character here. I love Kelly in this, which is especially interesting given that I find him pretty boring as a romantic lead.

It’s such a crazy turn of events. That and the fact that he did indeed die right after the trial blew my mind. Shoutout to Kevin, a guest on our podcast episode embedded in this post, for giving lots of insight into how crazy the trial was.

I didn’t know much about Mencken prior to reading more about this trial the past couple weeks. He invented the term “Bible Belt” and has about a million pithy quotes floating around the internet.