"I want my two hundred dollars"

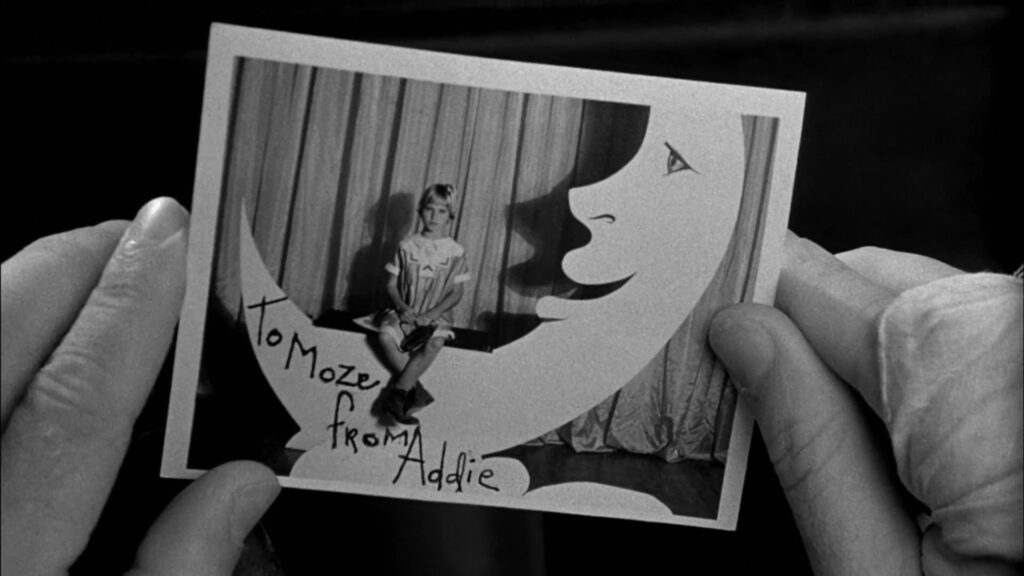

There’s a scene set at a carnival about halfway through Paper Moon when nine-year-old Addie Loggins (Tatum O’Neal) gets a portrait taken by herself at a carnival — perched on a crescent moon. This snapshot is lovely and heartbreaking, and it’s used as the iconic poster for the movie.

But hold on. That it isn’t quite right. The poster has something else: Another person. Moses Pray (Ryan O’Neal) aka Moze, the man taking care of Addie, joins her on the moon in the poster.

So which is it? Alone or together? The photo in the film serves a narrative purpose, and the poster serves a marketing one, but I find the tension between these two images cuts at the heart of this terrific dramedy. The film is all about the struggle for a child-figure and father-figure to fall in sync and figure out their future: Alone or together.

Peter Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon is a Depression-era con artist road movie, but it has the gentle touch of a bedtime story. It’s all about finding a balance between grit and warmth: Addie and Moze make one of cinema’s most charming and unconventional father-daughter pairings, yet they are crooks. Heck, they’re not even really father-daughter pairing: the biology, legality, and basic ethics of Moze’s guardianship over Addie are murky at best.

The story opens with the funeral of Addie’s mother, who was what you might call “a woman of ill repute.” She frequented bars and never settled down with a man. Moze reluctantly takes in Addie. He’s a small-time Bible-selling grifter who shows up at the funeral. What his connection is to Addie’s mother (and Addie) is unclear. But what comes next isn’t: Moze plans to dump Addie off at her aunt’s as soon as possible, though not before he uses her to scheme a local man out of $200. After a disagreement about who gets the money, Addie and Moze decide to stick together for a bit and hit the road in a 1936 Ford V8 De Luxe, hustling gullible widows and uptight shopkeepers. Their adventure is episodic and free-flowing, a balance of gentle and tense. It’s a hangout movie with a petty crime problem.

What makes the film sing is the phenomenal chemistry between the O’Neals, real-life father and daughter. The pairing is lived-in and occasionally biting in ways that a casting director couldn’t manufacture. Bogdanovich and the O’Neals sketch Addie and Moze in similar ways, both souls forged to live independently by necessity, but clearly in need of the support they’ve found in each other. And yet their relationship is never saccharine. It’s more cranky and pragmatic than affectionate, but always thrumming with authentic connection.

Bogdanovich and cinematographer László Kovács shoot the film in attractive black-and-white. The film texture is wonderful: Kovács works with a red filter (according to commentary track, Orson Welles suggested the filter to Kovács), delivering gorgeous, old-timey photo contrast to the cinematography. But what really makes the film look special is the incredible camera direction by Bogdanovich: Extended takes, slow Steadicam pans, and a clear eye on the excellent production and action give the film tremendous immersion. It’s especially noticeable during the tactile driving sequences, which make those rear-projection shots you usually see in pre-CGI films look especially tacky. You can practically feel the gravel kicking up and the characters barely hanging onto their seats as Ryan O’Neal (visibly not a double) swerves old cars through dusty streets.

Tatum O’Neal, who won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress at age 10 for her turn here (still the youngest competitive winner ever), is the best in show, even among the accomplished set of grown ups in the ensemble. Addie is sharp without being precocious, wounded without being maudlin. It’s a complicated and engaging performance. It’s frankly an upper tier child performance all time. Meanwhile, Ryan O’Neal plays Moze as a man of wounded pride, stubborn while still being a charming himbo. But it’s really the ways they play off each other that makes each performance so good; little reactions and facial expressions and turns of phrase in their dialogue.

Madeline Kahn shows up midway through as Miss Trixie Delight, a “dancer” (barely veiled as a prostitute) with a big personality and bosom, plus a bladder condition that’s a stand-in for an STI (she always has to go “winky-tinky”) . She nearly hijacks her stretch of the film as a comic whirlwind, for better and worse. Kahn earned a Best Supporting Actress nomination as well. Her arc culminates with Addie and Trixie’s assistant Imogene (P.J. Johnson) pulling a heist to sabotage, one of the best stretches of the film.

What’s most striking about Paper Moon is its tonal tightrope walk. It’s a movie that could easily veer into sentiment or cynicism given the investigation of Moze as a reluctant parent, but it never does. The script by Joe David Brown and Alvin Sargentis is terrific from start to finish, funny and quick-moving.

Nearly impressive as the direction and the writing is the production. Bogdanovich and his team deliver some terrific period details and settings to capture that Dust Bowl desolation, nostalgia without rose-colored glasses but also without the dreariness you typically associate with Great Depression fiction. It’s much less alienating and cruel than many of its New Hollywood ilk, a four-quadrant crowd pleaser that I’d recommend to pretty much any audience, cinephile or casual. If anything, it’s too lightweight and breezy — Moze and Addie get comeuppance for their crime, but the film still goes easy on them.

What I keep coming back to is the film’s storytelling savviness. The film never answers its central question: Is Moze really Addie’s biological father? But it’s moot. During an economic downturn, whether in the ‘30s or ‘70s, the American heartland does not provide simple answers to complex problems. What matters is that whenever Addie and Moze drive off into their horizon in their whitewall tire Ford, their bond is more genuine than any “paper moon” or “cardboard sea.”

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.