Long live the new flesh

The fans of the popular podcast My Favorite Murder call themselves “murderinos.” I know this, because I used to be a murderino.

I had a long commute to a shitty job, about an hour of driving in western Massachusetts, and I needed something to fill the air. My Favorite Murder kept showing up in Apple’s Top 10 most popular podcasts, so I downloaded a chunk of episodes and hit play.

The hosts of MFM have maintained that their podcast helps their overwhelmingly female listenership in a couple of ways: one, by promoting mental health; two, by teaching women how to not get murdered. In an email exchange with The Atlantic, co-host Georgia Hardstark writes, “It’s a lot like exposure therapy, where you have to confront your fear to prove that it can’t actually hurt you. Basically neither of us are willing to let our horror of true crime keep us from our fascination [with] it. Reading an awful story and then thinking, ‘We have to talk about this on the podcast!’ instead of, ‘I have to hide this from my Google history!’ makes all the difference.” Framing your popular comedy show about the worst days of other people’s lives as “exposure therapy” is interesting: you have to wonder if the last thoughts of the black gay men Dahmer hacked to pieces to shove in his fridge were something along the lines of, “I hope the white middle-manager listening to the grisly details of how my head got pickled feels a little better about herself as she fires one of her employees for taking long lunch breaks.”

The MFM hosts are performing a really odd kind of magic trick here, a variation of the saw the woman in half trick, but where they saw the woman in half, then walk out to the front of the stage and explain how they’ve learned to be less afraid of being sawed in half (meanwhile, the woman sawed in half stays sawed in half). Abracadaver. I listened to the podcast for a while on these long commutes; the stories of the murdered women (and, rarely, men) were grisly, of course, but I had this uncomfortable feeling that after a year of listening, and hundreds of hours of “exposure therapy,” I still didn’t really know any better how not to get murdered, besides some obvious best practices: don’t be a person of color (👍), don’t be a sexual minority (😮💨), don’t be a sex worker (👍).

I stopped listening, and began to see the increasing popularity of the True Crime genre as another symptom of a terminally sick society that, instead of choosing to help people of color, sexual minorities, and sex workers, was doomed to merely empower white women on their morning commutes.

This is all a long preamble to talking about the film Red Rooms, which released in 2023, but nobody you know has seen. That’s changing a bit: an upcoming Blu-Ray release for the film seems to be sparking new interest on Letterboxd.

Red Rooms is a 2023 French court drama that was perhaps overshadowed by the other big 2023 French court drama, Anatomy of a Fall. That it’s a far better film than Anatomy of a Fall is selling it short: Red Rooms is easily in the top five films I’ve seen in 2024.

The story follows Kelly-Anne, played by Juliette Gariépy, a model and online poker player who is attending the murder trial of a man named Ludovic Chevalier. In one long, unbroken shot, the camera floats through the courtroom as the prosecution introduces the case: Ludovic is accused of murdering three teenage girls, filming the murders, and broadcasting them online. The nominal red room is something of an urban legend, a nightmarish space where murder is transformed into grotesque spectacle for others. David Cronenberg played with the red rooms legend in Videodrome, sending James Woods on a hellish investigation into a cult that is using red rooms to, paradoxically, purge society of the kind of viewer who would actively seek out this content. Videodrome’s most famous line—“Long live the new flesh”—is a sort of prophetic prayer for the media space Red Rooms is exploring in 2023, one where a woman like Kelly-Anne can become her own kind of murderino for the worst days of three young girls’ lives.

Who is Kelly-Anne? The camera, in this long, unbroken opening shot, finally settles on her in the courtroom audience. She’s lovely, in that French way: eyes as big and round as macarons, and a stare as cold and cutting as a guillotine. She sleeps in a cubby outside the court building. She’s the first in line at the courtroom security checkpoint. She takes the same seat in the far back row of the courtroom, the victims’ parents shoulders facing her. Is she homeless? No. She has a nice high-rise apartment, we learn, where she seems to spend most of her time playing video poker and earning outrageous sums in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. She only seems to consume smoothies. She is also a model, dressing in high fashion couture, posing enigmatically at a series of photoshoots. We never see her taking pleasure in these pursuits: there is a grim efficiency to Kelly-Anne’s life that narrows her pursuits to two domains: making money, and attending Ludovic’s trial.

Who is Kelly-Anne? We will be asking this question over and over for the next two hours, as we rarely leave the presence of Kelly-Anne, but whose motives and psychology become more and more inscrutable (and alarming) as the movie goes on. Is she a murderino like the MFM listeners, trapped in a fan’s echo chamber of empowerment and therapeutic best practices? Or is she… something else?

There’s another woman who keeps attending the trial, a mousey freak named Clementine, who catches the eye of Kelly-Anne. They share a lunch at break, and Clementine reveals what kind of murderino she is: more or less, she’s in love with Ludovic. Clementine gives an impassioned defense of Ludovic’s innocence, noting that the evidence the prosecution is relying upon is flimsy—that masked white man in the red room tapes, while he looks like Ludovic, could be any of a thousand white guys in Montreal. Kelly-Anne listens to Clementine dispassionately. Kelly-Anne looks, in fact, like a predator regarding some perfectly stupid prey. We understand pretty quickly that Clementine is a lunatic of a sort; she has that crazed, cultish energy of a Manson follower, of someone who can’t see beyond the quivering penumbra of their horniness to the grisly subject of their horniness (horniness usually requires this kind of defective vision).

Kelly-Anne doesn’t seem horny for Ludovic, nor for Clementine. In fact, Kelly-Anne doesn’t seem at all sexually motivated—though she invites Clementine back to her apartment, she makes no move to fuck. She seems to pity Clementine: the girl has traveled from the provinces to Quebec, and is running out of money. She says Clementine can keep her things at her apartment. She shows Clementine her computer array, and the artificial intelligence that she has programmed herself. We learn Kelly-Anne is quite good with computers, and with masking her online presence.

The trial progresses. Clementine and Kelly-Anne are now sleeping outside the courtroom together. The camera begins to take more interest in the victims’ parents, in particular Francine, the mother of the youngest victim. We learn that two tapes exist for the two other victims, but the third tape for Francine’s daughter was never found. In interviews with the press, Francine actually calls out the presence of Kelly-Anne and Clementine and the other murderinos attending the trial. One of the bitter ironies of fair and public trials is that they must be open to the public, which of course means that a murderino like Clementine, horny for Ludovic, is allowed to attend the same back-and-forth discussions of how your daughter was dismembered.

Kelly-Anne, so good with computers, discovers the address of Francine’s home. She goes on the dark web and… figures out Francine’s front door passcode. She begins to stake out the mother’s home, walking up to the memorial for her slain daughter, walking up to the windows. She peers inside. She goes to the front door, unlocks it, turns around, leaves.

Who is Kelly-Anne?

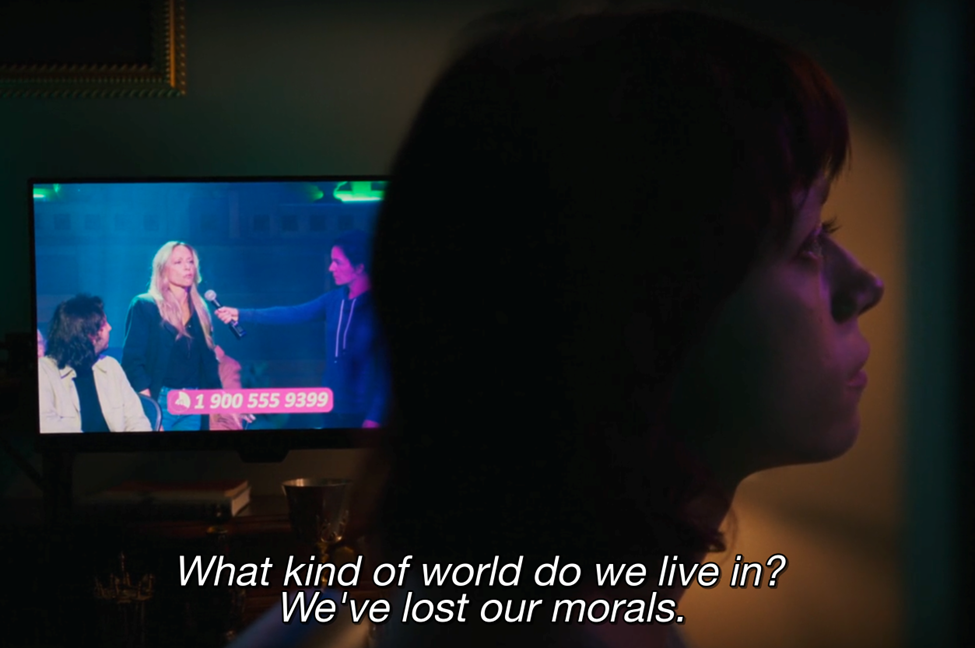

In one virtuosic scene at Kelly-Anne’s apartment, she and Clementine tune into a call-in TV show discussing the Ludovic case. Kelly-Anne projects the show on one of her apartment’s empty walls, while Clementine calls in. The hosts pity Clementine. They say she has been corrupted by the media, by her own foolishness. The framing of the scene, with the computer monitor positioned behind Clementine, and Clementine staring at the projection on the wall, suggests that people like Clementine live in a maze of mediating screens, the stories we tell about guilt and innocence, about empowerment and therapeutics, sold to an audience that has already made up their minds about their own righteousness (that their minds are made up of what they consume goes, gracefully and conveniently, unacknowledged).

The hosts hang up on Clementine, who is left in bitter tears. She knows Ludovic is innocent. She just does. This is when Kelly-Anne does something unlike herself, so far as we know her: she asks if Clementine would like to see the red room tapes. How on earth does Kelly-Anne have them, Clementine asks. Kelly-Anne tells her about the dark web, about media secreted inside media, screens within screens. Clementine agrees to watch the tapes, and the film pulls off another great trick: instead of showing us the tapes, it shows the two women watching the tapes. Their faces are bathed in red light. Clementine’s eyes begin to shimmer with tears. We hear horrible sounds from the tapes. Clementine looks as if she is about to vomit. Beside her, Kelly-Anne’s inscrutable face. What is she feeling? Her face changes like a glacier calving changes: one elemental coldness collapsing into another elemental coldness. She blinks. She stares. She looks over to Clementine, reduced to a quivering mess. The tapes end, and Clementine rushes to the bathroom to vomit. The next day, Clementine moves out of Kelly-Anne’s apartment and leaves Montreal.

It’s at this point that I won’t go further into what happens in Red Rooms, because the film still has some incredible and disturbing surprises. A late scene in the courtroom, involving Kelly-Anne and a costume change, had me screaming out loud in astonishment, then laughing at my own astonishment. There’s a climactic scene, too, that involves an auction and ungodly amounts of bitcoin that is shot and edited like a taut thriller. Even though what Kelly-Anne is bidding on is unspeakable (as is what she plans to do with it), I found myself rooting for her. Like a rabid murderino.

In this regard, Red Rooms’ greatest trick is probably getting you to empathize with a true freak like Kelly-Anne, who will go down alongside the Woman in Scarlett Johansson’s Under the Skin as one of cinema’s great freak fatales. There are limits to this kind of synthetic empathy, of course: regarding the pain of others isn’t the same as experiencing their pain. (Just as regarding freaks does not necessarily make you a freak—though maybe you ought to stop doing that.) Susan Sontag noted this distinction in her famous essay of the same name, Regarding the Pain of Others. Sontag, after interrogating the value of war photography, arrives at a place of empathetic uselessness. She writes,

Engulfed by the image, which is so accusatory, one could fantasize that the soldiers might turn and talk to us. But no, no one is looking out of the picture. There’s no threat of protest. They are not about to yell at us to bring a halt to that abomination which is war. They haven’t come back to life in order to stagger off to denounce the war-makers who sent them to kill and be killed.

The victims in the red rooms aren’t looking out at their audience. They aren’t interested in shaming them for looking. For wanting to look. Their interests are far more immediate: they are begging to have their lives spared. Sontag goes on to say of the dead that they are “are supremely uninterested in the living: in those who took their lives; in witnesses—and in us. Why should they seek our gaze? What would they have to say to us? ‘We’—this ‘we’ is everyone who has never experienced anything like what they went through—don’t understand. We don’t get it. We truly can’t imagine what it was like.

So what is the appeal for the murderino? For Kelly-Anne? Why do we want to look into these red rooms at all? For Sontag, the answer is simple: these photographs let us feel lucky that it wasn’t us. The red room is a relief, in this regard: it is their red room, not ours. When the hosts of My Favorite Murder say they are empowering their murderinos, they’re saying this: you are not dead. Congratulations.

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Jonathan Volk writes and teaches writing in western Massachusetts. He has served as Academic Director at the Great Books Writer’s Workshop, and will be teaching poetry at Clark University in the spring. He is working on a novel. Follow him on Letterboxd @ThixthThenth.

6 replies on “Red Rooms (2023)”

Spelling it “white woman” while pronouncing it “bitch” sure was a valuable linguistic innovation we came up with six or seven years back. Nothing but good results.

??

I’d say a fair summary of your first 500 words is, “stupid women, who are stupid and possibly shouldn’t even have jobs where they oversee others because sometimes they enforce workplace rules, are ruining society by listening to podcasts that I think are gauche, and therefore I should quite literally wave the bloody shirt (or, as it were, the pickled head), in pursuit of a moral panic that I’m gendering, even though I probably I don’t have to.” I mean, is true crime bad because it’s *bad*, or is true crime bad because, something like a century-plus after its development as a genre, true crime podcasts with “an overwhelmingly female listenership” became popular? I’m foggy on the mechanism for how “true crime” is making society collapse all of a sudden, given that as long I’ve been alive, there have been people obsessing over lurid crimes while serial killers and the like have been commercialized and used as totems, sometimes in hugely inappropriate ways. (Hell, women didn’t do that, Jack the Ripper did that.) It’s not beyond critique–I think true crime’s boring and repetitive, and of course it can be ghoulish–but there are definitely Internet phenomena with much more obvious mechanisms for making society collapse than that, for instance, the need of social media discourse to continually come up with novelties, such as “listening to true crime podcasts makes you evil,” so that we spend a whole lot of time and energy pointlessly accusing each other of some transgression. Not dissimilarly to what I’m doing right now. Sigh.

But if society fucking ends it’s because not enough dudes voted for a chick, just like it almost ended the last time that happened. Now, either one may have fired someone for taking too long on their lunch break; sure, I agree, they both seem like the type.

to be clear, white women are in like my top 150 kinds of women.

Another tip for how not to get murdered: Avoid equating the French with the Quebecois.

Can’t wait to watch this, though.

Hi-diddly-ho, murderinos!

(Since I shun ‘True Crime’ and have never watched this film, this will be my sole contribution to this review: fair warning, this greeting will be a recurring joke).