The game is afoot

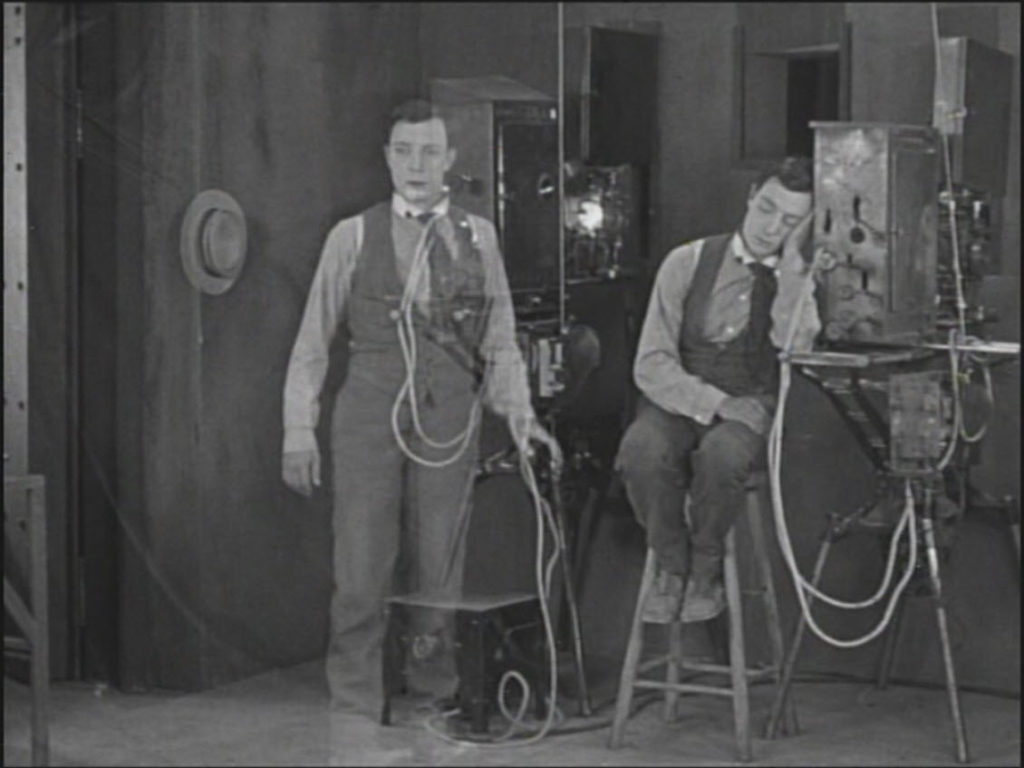

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a man who watches too many movies will be a dweeb. Whether it’s Marvel, Star Wars, or Sherlock Holmes (as seen here), genre film superfans are stereotypically dorks who have trouble coping with reality or landing romantic partners. In his 1924 comedy Sherlock Jr., Buster Keaton presents a prototypical cinephile with affectionate skewering. Keaton stars as a nameless movie theater projectionist obsessed with the mystery films he screens. When he’s falsely accused of a crime and dumped by the girl he’s wooing, he retreats to his true love, cinema, and drifts into a dream where he’s the suave, ingenious Sherlock Jr., the world’s greatest detective. It’s a parody of, and love letter to, “movie magic” and the obsessives who fall under its spell, told with Keaton’s signature cocktail of jaw-dropping physicality and unflappable deadpan.

Sherlock Jr. is Keaton’s third feature film (if you count 45 minutes as feature length) and first solo directing credit. He’d made his name with shorts and had recently graduated to longer-form storytelling with Our Hospitality, a charming riff on the Hatfields and McCoys. That film showcased his knack for storytelling and long-form gags, though it’s ultimately restrained compared to the comedian’s peak slapstick. Sherlock Jr. marks a startling leap forward: it’s not just funnier and tighter, but more radical and visionary. It’s where Keaton reaches a higher level in direction, editing, and creativity. It’s here where he starts to earn a reputation as one of the all-time greats.

The first act of the film takes place in “real life.” Keaton’s projectionist is smitten with “The Girl” (Kathryn McGuire), but his attempt to woo her with $1 worth of chocolate and a pawn shop ring goes south when he’s framed by a rival suitor (Ward Crane) for stealing her father’s pocket watch. He’s cast out from her home and slinks back to his job at the theater.

Heartbroken and slouched in the projection booth, Keaton drifts off mid-showing and emerges as a double-exposed dream spirit. His sleeping self then performs what is simply one of the greatest visual tricks in movie history: Keaton walks down the theater aisle and steps directly through the silver screen and into the movie itself. The mise-en-scene of the movie-within-a-movie shifts across various genres and settings (jungle, romantic balcony, train tracks, snowy cliff, etc.), with Keaton baffled at his changing surroundings. The seamless editing and staging show the world transform around Keaton with each splice of celluloid. This sequence is a hyper-speed montage of smash-cut gags, but pinned around the human who remains unedited as the rest of the film changes. It’s hilarious and a mind-boggling achievement of creativity and cinematic craftmanship, plus a timeless symbol of the transporting power of cinema.

(Between Enchanted, Teen Beach Movie, Purple Rose of Cairo, and this, I have come to the realization that I am a major sucker for any story in which characters breach the film screen in one direction or the other, movie character entering the real world or vice versa.)

From there, we witness a meta-movie take shape in his dream recreating the drama Keaton’s real-life character is facing. The dream-movie refracts the framing story’s actors as heightened archetypes: Keaton’s theater-jockey schmuck becomes Sherlock Jr., all confidence and wit, a startling contrast to the downcast projectionist. McGuire becomes the damsel in distress, and Crane the moustache-twirling and scheming villain. This dream mirrors and fuels the drama of the framing story — can “real-life” Keaton solve the mystery and get the girl like Sherlock Jr.? Can Keaton extract some movie magic to the external world to make his own happily ever after?

The framing story merging with the movie-in-a-movie is the core joke and image of the film, but it’s not the only great gag here; not by a long shot. In fact, Sherlock Jr. is pretty dense with all-timers. Keaton strings together a highlight reel of death-defying stunts and kinetic mayhem. The most elaborate is a white-knuckle motorcycle chase with Keaton riding the hood of the bike, not realizing the driver fell off and thus the motorcycle is driving with nobody at the handlebars. Another stunner is when Keaton runs across the top of a real moving train timed perfectly to keep him center frame. Keaton remains stationary relative to the background like he’s on a conveyor belt. That set piece pays off with what was reportedly the most dangerous stunt of the film: a cascade of water from a tower flattening Keaton in a single, massive torrent. One perfectly executed take captures this entire sequence. Keaton apparently cracked a bone in his neck during filming the train and water tower gag, but didn’t even realize it until a doctor spotted the fracture years later.

It’s not just the big, dangerous stunts that elicit gasps and laughs. Sherlock Jr. thrives even in its smallest jokes. Keaton isn’t just executing spectacle, but comic misdirection and setup-payoff wizardry. Heck, the very first joke is a micro-masterpiece: Scouring the theater trash can for spare change, Keaton gives away multiple dollars to people claiming to have lost them, and just when you’re expecting the comedy “rule of three” to kick in, someone digs out an entire wallet from the trash pile that Keaton could have easily pilfered if he’d been properly doing his job earlier. I also dug a long buildup to a banana peel slip that is executed with such fluid ballet it could pass for Looney Tunes gag. Keaton’s genius isn’t just in how he moves, it’s in how he constantly operates space and rhythm and expectations in every joke.

That cleverness appears in the story and its writing, too. For all his big dreams, Keaton’s aspiring detective character isn’t the one who cracks the case — it’s McGuire’s Girl who pieces together the clues and clears his name. It’s an underplayed joke that builds across the runtime — the titular detective depends on someone else solving the mystery. Almost every moment gets weaved into some sort of later twist: For example, early on, Keaton alters the price tag on a cheap gift to impress McGuire; later, Crane’s villain uses that exact, faked price as “evidence” against Keaton. Even the height difference between Keaton and his rival, initially used for laughs, becomes a plot point when it becomes the break McGuire needs to solve the case.

One hiccup that I’ve never been able to shake is that Keaton’s character never gets a moment as the hero in the real world. He wakes up from his movie-dream, then The Girl appears and forgives him. But he doesn’t actually solve any mystery or undergo any arc. Of course, that’s the point: Movies aren’t real life. The framing story version of Keaton isn’t suddenly a hero just because he idolizes the ones he sees on screen. And if that means skipping Keaton’s character growth (or, rather, subverting it so that McGuire is on the receiving end) in favor of a clean 45-minute runtime where not a second is wasted? So be it.

Despite my hesitation about Keaton’s lack of arc in the film’s ending, there’s one final grace note that gives the film a warm sendoff that I wouldn’t change for anything. In the closing moments, Keaton gazes up at the movie he’s projecting, watching the romantic lead embrace his partner with effortless confidence. Keaton mimics the gestures in real time, stealing glances between the screen and his real-life girlfriend like a student cribbing notes during a test. (Buster Keaton’s eyes alone are funnier than any actor working today.) It’s one of the most endearing images in silent cinema: the dreamer, humbled, finally learning from the fantasy he escaped into. For all the film’s fourth-wall shattering and surrealist gags, Sherlock Jr. ends with an affectionate note towards the medium: the movies teach Keaton how to expand his heart and express his love.

Sherlock Jr. came out 101 years ago, in 1924, less than a decade into the history of feature film as an art form. Already, the era’s best comic director is cracking postmodern riffs on tropes and inventing meta-cinematic grammar. Sherlock Jr. isn’t just a resoundingly funny movie: It’s the moment cinema turned the mirror on itself and had a hearty laugh at what it saw (part bitter, part loving). I’ve seen plenty of films older than Sherlock Jr. that are marvelous and worthy entrants into the canon of cinema history, but, as of this writing, this is the earliest one I purely adore with my 21st century eyes. It is timeless, inventive, ceaseless comedy magic. Sherlock Jr. is the moment Keaton fully ascends into greatness, and, to my eyes, cinema as an art form properly did the same.

Is It Good?

Masterpiece: Tour De Good (8/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.