Mad Dog; new tricks

(FULL SPOILERS FOLLOW)

…And now, we arrive at the important bit.

I told myself going into this whole project that I wasn’t going to skim over anything. I want to create the most comprehensive, in-depth account of my favourite working action director’s career that I’m able, and that means digging into the corners as well as the highlights. But, let’s be real here: as much as I might get a kick out of extricating the minutiae of Footsteps or Merantau, I knew perfectly well where it was all leading. Sure, I like Merantau a lot, and it attracted some international attention in 2009 from action-movie enthusiast sites, and those of us who squandered our time in university poring over shelves of imported southeast Asian films, the ones released on labels like Hong Kong Legends and Tartan Asia Extreme. But it wasn’t considered a success upon release in Indonesia, and it didn’t attain the critical mass overseas that would have made it a breakout hit.

The Raid, though? The way it blasted into the zeitgeist in 2011 and 2012 was dizzying to witness. Here was the new film by the guys who made that one nifty silat movie I’d liked a couple of years ago, I thought at the time. The original red-band trailer looked pretty fucking hardcore. Some cool, gnarly stunts; they were obviously going for a grittier, harder vibe this time. Maybe I, the guy my friends knew back then as the purveyor of weird, niche, genre stuff for our weekly movie nights, could convince my social circle to make an alcohol-and-pizza-fuelled evening of it. I was looking forward to it, not expecting it to make any great waves outside my own fanboy bubble.

The way [The Raid] blasted into the zeitgeist in 2011 and 2012 was dizzying to witness.

And then, The Raid (released in America under the modified title The Raid: Redemption, which I absolutely will not be using to refer to it) tore up the festival circuit. It won Best Midnight Madness Film and the People’s Choice Award at TIFF 2011. It earned rave reviews with perfect scores, not just from special-interest outlets like City On Fire or ScreenAnarchy, but from the likes of The Guardian and Empire Magazine. Gareth Evans was interviewed by Simon Mayo and Mark Kermode on BBC 5Live, with millions of middle-class British listeners tuning in to what he had to say. Roger Ebert, famously, hated it. This was all such a paradigm shift. For someone like me, who was already on the Evans/Uwais bandwagon, it was like the bandwagon had suddenly sprouted solid-propellant rocket-boosters and launched into low-Earth orbit.

And that acclaim wasn’t just a flash in the pan, either. Ten years on, The Raid is widely remembered as an integral piece of action cinema canon, spoken of in reverent tones by devotees of the genre. When Tom Breihan was putting his column “A History of Violence” together for the AV Club in 2017, documenting the most influential action film of each year from 1968 through to the present day, there was never any doubt that The Raid would be included (the only doubt was to whether it would be counted as a 2011 film, for its Indonesian release date, or 2012, for its international rollout. Breihan ended up going for the latter). Its star performers have gone from strength to strength in the years since, finding prominent roles both at home and overseas (Joe Taslim got significant supporting roles as a villain in Fast & Furious 6 and Star Trek Beyond; Iko Uwais and Yayan Ruhian had a joint-cameo appearance in The Force Awakens, for goodness’ sake). It spawned a wave of imitators both at home in Indonesia, and in neighbouring countries from Cambodia, to Russia, to the Philippines.

Hollywood noticed the reaction that The Raid’s hard-hitting, unflinching style was drawing out of people, too. I’m almost certain the Russo Brothers were fans – as early as 2014, there’s a beat in a fight scene in Captain America: The Winter Soldier I’m positive was cribbed straight from The Raid. It served as a vanguard ahead of the John Wick franchise, and in turn, the proliferation of 87North’s school of action design. If you really wanted to stretch a point, you might go as far as to claim The Raid inaugurated a new (better) era of action movies; a tidal shift away from the trend of frenetically cut coverage with sound-design filling in the gaps in the wake of the Bourne franchise, towards an emphasis on visual clarity and impact.

If you really wanted to stretch a point, you might go as far as to claim The Raid inaugurated a new (better) era of action movies

Not bad, for a film that was originally devised as a backup plan.

After Merantau landed at Indonesia’s domestic box office to a muted reaction, Evans and Uwais went back to the drawing board. Evans drafted a script for a film titled Berandal (the word approximately translates to “thug” or “hooligan” in English), a crime epic with the lead role intended for Uwais, incorporating the unique rhythms of the action design they’d pioneered together into a plot with the scope of something like The Godfather or Scarface. They produced a proof-of-concept teaser consisting of a rough-and-ready version of what would eventually become the toilet-stall fight in The Raid 2. A year and a half went by, being told “no” in meeting after investor meeting; the script for Berandal was too ambitious, and would cost too much for financiers to sign off on. Finally, Merantau Films realised they had to scale back their ambitions in the short term; if they were going to move ahead with their mission to represent Pencak silat on film and make a martial arts star out of Iko Uwais, then necessity would be the mother of invention.

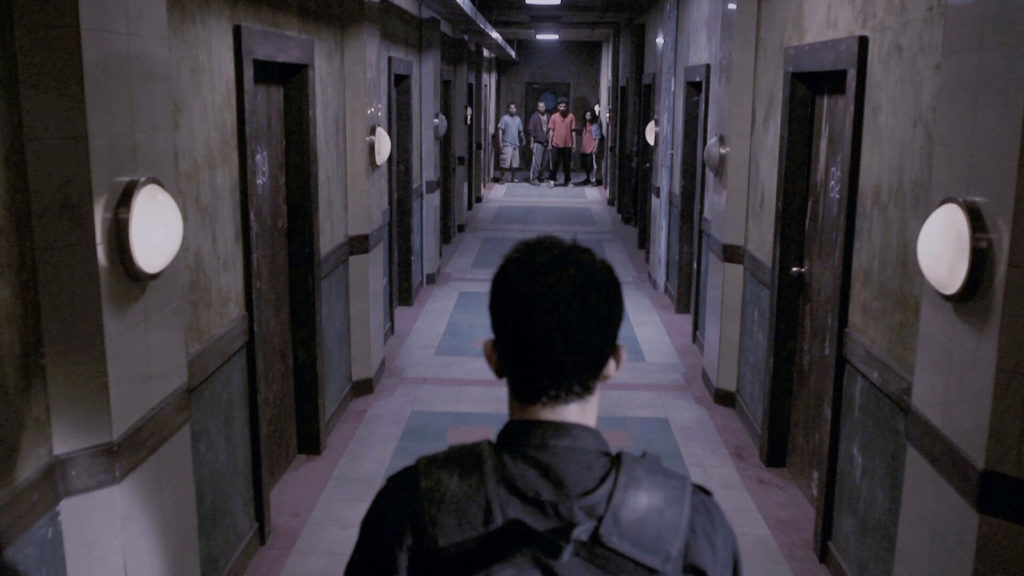

Thus, The Raid: a film conceived from the ground up to gain maximal returns from minimal investment. With a reported budget of about $1.1 million USD (less than Merantau), it tells the story of a SWAT team assaulting a high-rise apartment block in the slums of Jakarta that for ten years has been the fortress of gangland kingpin Tama Riyadi (Ray Sahetapy), who leases apartments to all and sundry criminal elements. Our protagonist is Rama (Iko Uwais), a rookie with a pregnant wife waiting back home and tremendous skill in Pencak silat. He also has a cryptic personal motive for being part of the team in this raid; in a mid-film twist that’s very Heroic Bloodshed, it’s revealed that Andi (Doni Alamsyah), one of Tama’s lieutenants and the brains of his operation, is Rama’s estranged brother, who Rama has pledged to bring home.

The infiltration goes wrong, pretty much immediately; the SWAT team is spotted by a sentry and overwhelmed in a firefight when Tama rallies the building’s residents against them. Making matters worse, it’s revealed that their operation is unsanctioned and illegal; Lieutenant Wahyu (Pierre Gruno), the senior officer responsible for putting the raid together, is a corrupt cop on the books of one of Tama’s underworld rivals, leaving them without backup and without escape, stranded in enemy territory with hundreds of antagonistic criminals who have nothing to lose. The cops who survive the initial firefight – among them Rama, Wahyu, and the brusque, unflappable team leader Jaka (Joe Taslim) – have to run, hide and fight their way through the building’s nooks and crannies, trying to find a way out alive, surviving from moment to moment by their ingenuity and their grit.

And that’s the movie; a scenario of ruthlessly limited scope, containing a breathless chain of masterful action set-pieces, each one topping the last; as concentrated a shot of adrenaline as there is to be found anywhere within the medium.

…as concentrated a shot of adrenaline as there is to be found anywhere within the medium.

Talk about art flourishing within limitations. The Raid’s single-location conceit, for example, was born largely out of a desire to avoid shooting in Indonesia’s hot, wet climate, where shooting could frequently be delayed by variable light levels and heavy rain. Excluding a handful of exterior scenes near the beginning, the vast majority of scenes (and all of the demanding stunts) take place within the same handful of interior studio sets, where the crew could shoot for hours and hours without regard for the time of day. You can see artefacts of this choice littered throughout the film; in almost every shot where there’s a window that should have a view out of the building, all we can see is a featureless rectangle of bleached off-white added in post-production, meant to suggest the glare of the sun but which clearly doesn’t act as a light source upon the set.

It’s the sort of trick that, on paper, sounds like a cop-out, but it’s just one instance where the frugality of the production ends up making the final product more effective. The cops feel profoundly trapped within a black hole of criminality, where not even light enters or leaves without Tama’s permission. That sense of claustrophobia is reinforced throughout. DP Matt Flannery does a 180 from his work in Merantau; where that film was bright and colourful to look at, The Raid is powerfully desaturated, the colour palette a very seventh-console-generation medley of greys and browns. Everything in Tama’s domain looks so utterly squalid and grimy, the filth accentuated by the dingy lighting that suggests a forty-watt bulb smeared with grease. It’s not underlit – far from it, we can see everything we’re meant to in stark relief – but the suggestion of chthonic darkness is persistent, like the characters have inadvertently wandered into the Silent Hill nightmare dimension.

The stress and fear the characters are undergoing is reinforced by the tight shot-scales and the deployment of wide-angle lenses (on the order of 12mm to 20mm much of the time), giving us a good look at the SWAT team’s faces at their sweatiest and most unflattering when everything’s gone wrong, in addition to lots of roving handheld shots. The crew shot on the Panasonic AF100, a newly-released camera model at the time of The Raid’s production and much lighter than the shoulder-mounted HPX500 used for Merantau, giving the early scenes of the film an almost documentarian feel to them. Shots judder in concert with the camera operator’s footsteps, whip back and forth in attempts to keep the action in centre-frame, like we’re getting the POV of the world’s unluckiest journalist embedded within Indonesia’s unluckiest SWAT team. Evans has spoken about taking influence from Romain Gavras’s music video for the M.I.A. track “Born Free” for the film’s gritty, high-energy, boots-on-the-ground aesthetics, as well as Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza’s [REC] and [REC]² for their claustrophobic intensity. The Raid forgoes the more classical, stagey presentation of Merantau in favour of a filming style that feels subjective and spontaneous, but without sacrificing clarity.

That’s not to say that it’s aping the look of found-footage movies, or going for any kind of epistolary gimmick in its presentation. Indeed, if there’s one thing that’s clear throughout Evans’ and Flannery’s work together, it’s that they dislike and distrust gimmicks of any kind. The Raid isn’t trying to sell itself on the basis of any high-concept or novelty, the way movies catering to the same audience like Hardcore Henry or One Shot are. They consciously skirt any filming technique that might call attention to itself and to the movie’s artifice, pulling the viewer out of the moment. They avoid anything like body-cam shots or POV shots or action-replays. There are no show-offy tracking shots of the sort that have become a calling-card for action movies in the 2010s. They make only limited use of montage, and this is mostly confined to early scenes of the cops’ infiltration, as a means to get the place-setting out of the way as expediently as possible. They do occasionally use slow-motion, but only ever for evocative purposes, dilating and emphasising tense moments (like during the silent close-up on the shotgun muzzle-flash that ignites the big firefight in the first act). It’s never to emphasise how cool a particular high kick looks. The score* (composed by Joe Trapanese and Linkin Park’s Mike Shinoda) eschews catchy melodies, comprised mostly of layered swells of harsh electronic ambience that play up the setting’s sense of urban decay, to the point that it almost seems diegetic, bleeding together with the enveloping sound design (the soundtrack’s most recognisable motif is a series of shrill, syncopated stings that suggest the piercing wail of an intruder alarm). The only “gimmick” The Raid brings to the table is really, really, really, really, astoundingly strong filmmaking fundamentals. It uses the meat-and-potatoes of the medium to draw you into its verisimilitude quietly, invisibly, not even noticing how deeply you’re immersed until someone’s neck gets snapped, and you cringe in unison with the rest of the theatre at just how visceral the moment feels.

I’m about to say something about The Raid that might seem like I’m negging it, and I promise I’m not, so please bear with me. OK? OK. Here goes:

The martial arts on display in The Raid aren’t that impressive.

I absolutely don’t mean this as a knock against Iko Uwais, or Yayan Ruhian, or Joe Taslim, or any of the other performers and stuntmen involved in the film’s production, many of whom are champion-level practitioners of their disciplines, and who put life and limb on the line to produce a transcendent piece of entertainment. I know for a goddamn fact that I couldn’t do their job, out-of-shape coward that I am who spends his evenings critiquing other people’s hard work on Letterboxd, and the Oscars absolutely should have a Best Stunt category. But, the fact remains, a big part of the appeal of martial arts movies is to see the human body do incredible things; either things that we thought it physiologically couldn’t do, or things that no sane person would have the courage to do. When I show up to a movie starring Yuen Biao, or Mark Dacascos, or Tony Jaa, or Scott Adkins, it’s in the hope that they’ll show me a higher fall or a fancier kick or a faster, more elaborate combination than I’ve seen before. And The Raid doesn’t offer that; there’s no element of bodily activity here that would have especially raised eyebrows if it had appeared in, say, a Hong Kong movie in 1985.

But when I watch The Raid, what draws me in isn’t a newfound plateau of strength, or speed, or dexterity, or of performers putting themselves at suicidal risk. I’m not looking to see Iko Uwais execute a 1080 spin-kick where I’ve only previously seen a 720 spin-kick; that’s not the way it sets itself apart, any more than it does with any other prospective novelty factor. It is a martial arts movie, just to be clear on that point, but that isn’t its first or main generic allegiance. Merantau was constructed in large part as an exhibition for Pencak silat, designed to give Indonesian martial arts the spotlight first, and build an action movie around that. In The Raid, that emphasis is reversed. Silat is still the dominant martial art in the choreography, the tempo and the rhythms of the fight scenes dictated by its metronome. But other styles are brought into the mix: Taslim is a national champion in judo, with a grounding in wushu; Eka Rahmadia, who lays Dagu, is a Taekwondo practitioner. The cultural emphasis that played such a large part in Merantau is non-existent here. The focus in The Raid’s fight scenes isn’t on technique, but on savagery; on sheer kill-or-be-killed survival impetus.

The focus in The Raid’s fight scenes isn’t on technique, but on savagery; on sheer kill-or-be-killed survival impetus.

But what gorgeous savagery it is! The fight choreography hits an ideal sweet spot, where it suggests the scrappy desperation of the fighters involved, while still being aesthetically pleasing to look at, for the performers’ fine control over their bodies, and for their lightning-fast tactical choices. The characters’ decisions are legible in the ways they move. The Raid doesn’t realistically depict the brief, clumsy flail of limbs that comprise real-life fistfights where opponents are genuinely trying to hurt one-another, the kind of thing you might see in CCTV footage captured outside a dive-bar at 2.00 AM on a Saturday morning. Rather, it’s a heightened, stylised, artful expression of what being in such a fight might feel like; of having your brain swimming in epinephrine, split-second reflexes the difference between life and death; of searching feverishly for the optimal way to put the other guy down with minimal injury to yourself; of not feeling the pain yet, but knowing with dark certainty that you will later. Every fight sequence contains an embarrassment of riches; for minutes at a time, we’re treated to intricate combinations and exchanges, the choreography practically never repeating itself, always remaining suitably explosive and vicious, and punctuated regularly with punchlines of heart-stopping violence.

The Raid is a significantly more quickly cut movie than Merantau was. Evans talks in interviews about having taken advice in-between the two films from Mike Leeder (a critic and producer known as an expert on martial arts cinema), who told him that the long takes in his previous movie were tiring his performers out, and giving the audience more room to notice whiffed hits. Certainly, a quicker cutting rhythm suits a film like The Raid, where intensity is the first, second, and third priority. It keeps the pace feverish, and gives the performers license to sell their blows harder when the consequences of a botched take aren’t so dire. But there is definitely a cohort of action-movie fans whose hackles will be raised by phrases like “handheld camerawork,” “close shot scales,” and most of all, “fast editing.” “Fast editing,” in the minds of many of us who were burned by the worst excesses of the post-Bourne era, is too easily conflated with “bad editing.” But The Raid is a million miles away from the likes of Doomsday or Taken 3 or Resident Evil: The Final Chapter. It isn’t a slapdash assemblage of coverage footage, filmed from fourteen different angles at once and then stitched together in the editing room like so much necrotic tissue. Every shot was exhaustively pre-visualised months in advance of filming, the cast and crew working to a highly specific video storyboard. And you can tell. Every angle is optimised to allow the viewer the clearest view of the fight; every cut is motivated, directing the viewer down a straight line of causal logic, giving us the information we need for just as long as we need to internalise it. If Merantau was like listening to a guitarist play a gnarly lick, then The Raid is like hearing that same lick played at double the tempo but without any hit to the timekeeping.

I honestly can’t identify a weak link in The Raid’s construction – it’s a flawless version of itself, a diamond forged under the pressure of the circumstances that led to its production. But I suppose it is worth taking a step back and asking the question: is “flawless” the same thing as “worthwhile”?

It’s certainly not a film for everyone. The prevailing critical consensus since the film’s release has been very positive, but right from the start, there’s been a contingent of the general audience that finds The Raid deeply off-putting, that sees nothing more in it than a slog of plotless, pointless ultraviolence. Some of them are even people whose opinions I respect and value. In the late, great Roger Ebert’s one-star pan of the film, he begins: “This film is about violence. All violence.” He continues: “Have you noticed how cats and dogs will look at a TV screen on which there are things jumping around? It is to that level of the brain’s reptilian complex that the film appeals.”

And, look, I’m not going to try to score points off a celebrity film critic who, A) is someone whose body of work I broadly admire and whose writing I look to as an influence, and B) has been dead for ten years. But I do feel obliged to offer a rebuttal to this particular reading of The Raid.

First of all, The Raid isn’t quite the non-stop onslaught of skull-splitting action that the rhetoric around it tends to suggest. Watch: I have the analytics to prove it. The Raid contains six major action set-pieces, during which its characters are engaged in open combat. These are, in order:

1) The first big shootout, that starts when the SWAT Team’s presence in the building is compromised. Begins with the first volley of automatic weapons fire from the residents on the upper mezzanine floor; concludes with the fridge explosion. Timecode: 0.23.19 – 0.30.03

2) Rama’s fight in the seventh floor corridor, fending off attackers coming from all angles and trying to defend the wounded Bowo (Tegar Satrya). Begins with the first attacker jumping out at Rama with a war-cry; concludes when the eighteenth attacker has his head slammed through a light fixture. Timecode: 0.36.27 – 0.38.22

3) Rama’s fight with the five members of the Machete Gang. Begins when he’s spotted leaving room 726; concludes when he tackles the leader out of an apartment window and falls two storeys to land on the fire escape outside. Timecode: 0.48.58 – 0.53.21

4) Jaka’s mano-a-mano fight with Mad Dog. Begins when the two of them square off in the centre of the room, and Mad Dog throws the first kick. Concludes when Mad Dog breaks Jaka’s neck. Timecode: 0.59.47 – 1.02.25

5) The Drug Lab fight, where Rama, Dagu and Wahyu team up against a horde of goons. Begins when Rama throws a sentry off the balcony outside; concludes when he incapacitates the last of the mooks with a leg sweep. Timecode: 1.13.06 – 1.16.37

6) The final fight, which sees Rama and Andi team up against Mad Dog. Begins when the three of them square off in the middle of the torture chamber, and Andi throws the first blow. Concludes when the brothers pin Mad Dog to the floor, and an exhausted Rama slits his throat. Timecode: 1.19.13 – 1.25.52

Outside of these six main set-pieces, there are a few other flare-ups of action (Andi attacking the two men sent to escort him in the elevator; Mad Dog’s initial, brief scuffle with Jaka and Wahyu in the corridor). But even taking into account every such morsel, and applying what I feel is a reasonable but generous standard for what constitutes a “fight scene,” the total time The Raid spends engaged in fight scenes amounts to 27 minutes and 12 seconds. In the copy of the film I was working from for this review – the no-frills PAL-region DVD released in the UK by Momentum Pictures in 2012 – the total running time is 1 hour, 36 minutes, and 49 seconds. This means 28.09% of The Raid is fighting. The figure ticks up to 29.47% if you exclude opening title cards and end credits.

That is, by most standards, quite a high ratio. If you make a movie where three-tenths of the screentime is characters beating the piss out of one another, you’ve made a movie where fighting is a dominant theme. But what’s interesting to me is the content of that remaining 1 hour, 9 minutes and 37 seconds. Even fans of The Raid will often describe it like it’s a non-stop orgy of ass-kicking; I’ve heard it described more than once as a single, feature-length fight scene. Which rather raises the question; if the fighting is all that audiences take away from The Raid, what exactly is going through audience members’ minds in the scenes without fighting, which outnumber the scenes where there is by more than 2-to-1? I’m reasonably sure they don’t just lapse into a fugue state.

Thing is, I’ve seen movies with a fight-to-not-fight ratio considerably higher than The Raid’s. An instructive comparison would be Koichi Sakamoto’s 2008 film Broken Path. Like The Raid, it’s a low-budget thriller, confined to a single-location for most of its duration, where the stakes are life and death, and features a ton of highly choreographed martial-arts fight scenes executed by a roster of physically talented performers. You can look up scenes from that movie on Youtube which, in isolation, rock. But, unlike The Raid, Broken Path actually does spend the absolute majority of its runtime engaged in fight scenes. And, unlike The Raid, Broken Path in its entirety is almost unendurably boring. There’s no variation across its runtime; no escalation, no dynamics, just the same handful of performers doing slight variations on the same sort of choreography, over and over again. It’s repetitive, and monotonous, and it isn’t at all like The Raid.

Here’s the point I’ve taken the most pedantic, circuitous possible course to arrive at: Roger Ebert wasn’t incorrect to call The Raid a film “About Violence. All Violence.” The scenes where characters aren’t actively engaged in violence are spent in the looming shadow of violence; where the prospect of violence is immediate and palpable. When the cast aren’t committing violence, they’re finding spaces to hide from it; running from it; trying to bargain or bluff their way past it; recovering from it; bracing for it; advancing straight into it, whether with grim resignation or joyous abandon.

It borders on experimental in how spare and straightforward its scenario is, in how little it contextualises its events. It’s completely anchored in the present tense at all times, with any allusions to the characters’ lives, or the universe outside of this building and these couple of hours kept as vague and general as possible. I actually felt a bit trepidatious revisiting the film in 2023, considering that it’s a movie that uncritically depicts a lot of police brutality against the socially marginalised, who are framed as borderline-inhuman predators; that sort of thing doesn’t fly as easily now as it did ten years ago. But honestly, I don’t really think it plays as problematic, simply because The Raid is so transparently, obviously disinterested in situating its action in any sort of real-world social context. We’re in the realm of pure pastiche, playing “Cops and Robbers” in a sandbox of genre tropes. The cast’s actions aren’t motivated by any ideology or notion of justice; nor even particularly out of fealty to their squadmates, or to the family and friends that might be waiting for them if they make it out alive (even the one significant plot complication the screenplay adds – the reveal that Andi is Rama’s brother – is notable more for how it changes the strategic dynamics of the situation than for any emotional dimension it might introduce). The stakes, at all times, are “how will the heroes survive the next ten seconds?” It’s fight-or-flight; do-or-die; kill-or-be-killed; any motivation more abstract than that scarcely registers.

It borders on experimental in how spare and straightforward its scenario is, in how little it contextualises its events.

Where I disagree with Ebert is that he considers this a failing, where I see it as The Raid’s boldest choice and greatest success. By eliding the cursory plot machinations and character arcs that most fight movies will include out of obligation, Evans and Flannery free themselves up to build a story entirely out of the genre elements that get audiences in the door. Put it this way: if screen violence were pure alcohol, then The Raid would be a premium, single-malt whisky. Sure, if you take the alcohol out of it, what you’re left with isn’t much of a drink. But the pleasure involved in drinking it is more multifaceted than the buzz you’d get from simply guzzling medical-grade ethanol. There’s, like, a finish, and different flavour notes, and stuff. (Flavour notes are a whisky thing, right? I don’t drink whisky. This analogy was a mistake.)

The Raid is “About Violence. All Violence.” But within that violence, there are gradients. There are variances, subtleties, peaks and troughs. It’s expressive violence; evocative violence; the viewer’s emotions and sympathies and responses are guided in specific, fine-tuned ways by its presentation of violence. I’ll stake what might sound like an odd claim: despite having no idea what their lives might look like outside of their couple of hours in Tama’s high-rise apartment block, I feel like I have a pretty firm idea of who Rama, Jaka, Wahyu, Bowo, Andi, etc. are as people; I have a sense of their personalities.

Take Rama, for instance. We know from the opening scenes that he’s a Good Dude; a loving husband to a pregnant wife; a devoted Muslim; the kind of stoic, self-denying guy who gets up before sunrise to work out. We’re primed to think of him as a basically decent, nurturing person before the action starts, and it’s all pretty thin gruel on the page; but what interests me is the way that characterisation is maintained and consolidated when the action does kick off. Rama does some brutal, brutal things to other human bodies, it’s true. But there’s always a sense, in the choreography and the performance, that it’s something he does in spite of his better nature; that he’s made the calculated, deliberate decision to survive at all costs. He tries desperately to avoid conflict where he can, his first recourse always either to run or hide; but when it’s clear there’s no other option, he throws himself into the fray, allowing adrenaline to take hold and purposefully refusing to think of his adversaries as human, despite what psychic costs it might later incur.

Contrast him with Bowo; the Bad Cop of the team, shown to be aggressive and belligerent, hostile towards those he sees as beneath him. He’s the first to panic when things go pear-shaped, and the power he was all too happy to throw around as a cop is turned on its head, becoming a liability for his teammates; when he gets the chance to retaliate against the building’s residents, he does so with absurd, infantile overkill, screaming with fear and rage as he tries impotently to reassert the power dynamic where he feels comfortable. Or Wahyu, the corrupt lieutenant, who’s a self-interested, cynical snake with no regard for anyone’s life but his own; who’s content to shoot fleeing men in the back (hell; shoot fleeing children), who’s willing to make opportunistic alliances and then betray his comrades the moment their convenience expires.

I could go on, but I think the point is made; The Raid doesn’t rely on extrinsic circumstances to confer meaning upon its violence; it trusts its audience to infer meaning from the intrinsic qualities of how that violence is presented. One thing about the film that I think goes unduly unsung is just how solid the acting is across the board. No, none of the performers are tasked with dialogue worthy of Strindberg. But part of the point I’m trying to make here is how physical performances, stunt performances, can be no less crucial in creating a persuasive emotional reality, and the cast of The Raid are uniformly excellent at selling the film’s atmosphere of constant fear and tension and fight-or-flight adrenaline. In particular, Uwais is downright startling for how much he’s improved as a leading man since Merantau; in only his second screen performance, he’s vastly more confident and self-possessed in front of the camera. And I adore Ray Sahetapy as Tama, the seedy, soft-spoken, cold-blooded slumlord of an arch-villain; someone so secure on his squalid throne, omniscient within his closed-off, CCTV-monitored domain, that he’s come to regard life and death as wholly transactional propositions.

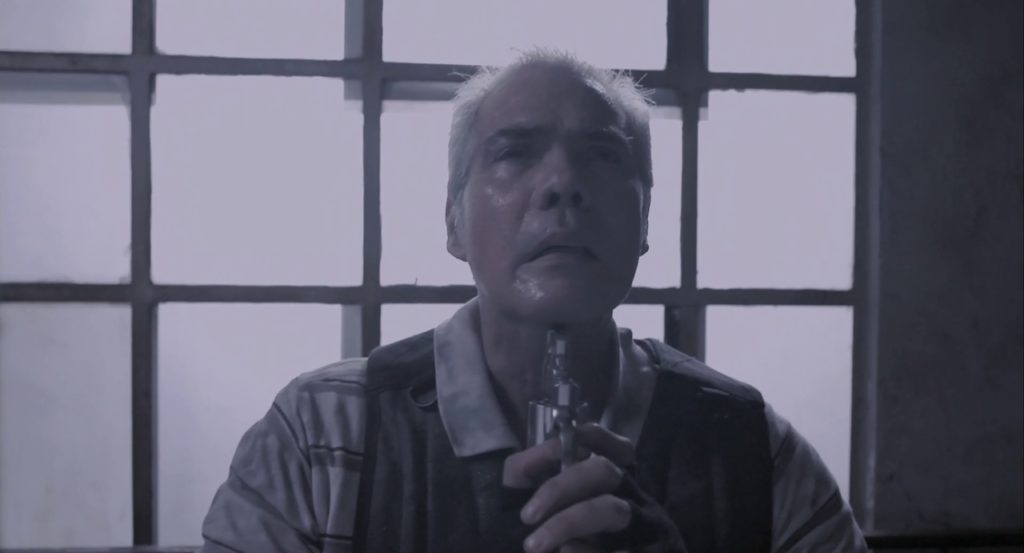

Best of all, though, is Mad Dog, Tama’s primary enforcer, played by Yayan Ruhian (also returning from Merantau, and who was responsible for designing The Raid’s choreography together with Uwais), and who’s one of my favourite antagonists in the last fifteen years of cinema. He characterises Mad Dog as a kind of Viking berserker, displaced in time and space; someone for whom fighting to the death against a worthy challenger isn’t just a job he’s good at, but something close to spiritual communion. In his battles with Jaka, Rama and Andi, he goes out of his way to level the playing field beforehand, ensuring as fair a fight as he’s able. When he fights, he does so with the wild, feral ferocity that presumably earned him his nickname, but there’s no sense of anger or hatred in it; just a complete, body-and-soul commitment to the experience of physical combat, paying no heed to pain or injury. When he has his opponents incapacitated and on the ground, he takes a moment, and raises his eyes skyward with a beatific expression; something like prayer, or post-coital bliss. To have all of this be communicated by movement, and gesture, and facial expressions, is so utterly cinematic. There’s no earthly way you could make this character any more compelling a presence by the addition of dialogue, or history, or context outside of the scenes where he’s beating people up.

And look, I’m not trying to be disingenuous here. I’m not trying to claim The Raid is a character drama in disguise: it isn’t. If I were to try to persuade a friend to watch it, I wouldn’t bait them with the claim, “well, if you pay attention, it’s really a character study about a man out of time, trying to reconnect with the spiritual realm through physical combat, bro.” That would be dishonest. My honest sales pitch would be more like, “holy SHIT, bro, there’s this scene where these three guys, they, they, they just absolutely BEAT the FUCKING TAR out of each other for six-and-a-half straight minutes, it’s insane bro, it’s the most awesome thing you’ll ever see!” I may have used that sales pitch a few times (perhaps not in those exact words), and I was telling the truth: it IS the most awesome thing you’ll ever see. But the key here is that what makes it so awesome is that there’s a human element catalysing all this violence; The Raid isn’t a sterile, inhuman product, quite the opposite. Fight-or-flight is a human reflex; the need to push through fear and stress and pain to survive just an hour, a minute, a second longer is a human impulse; and to dramatise that impulse through violent choreography is Valid Art. It’s the consideration given to character and performance, to the gestures in the margins, to the fine details of how that violence is meted out, that make The Raid a Great Movie, not just a great stunt demo-reel, or a handful of great scenes you look up on Youtube.

The Raid might be virtually free of plot; but it’s never not telling a story. It’s a film that describes reptile-brained emotions; but that doesn’t mean our appreciation of it necessarily comes from a reptile-brained place.

The Raid might be virtually free of plot; but it’s never not telling a story.

And, on that note, I present my official, ranked, Top 10 Moments in The Raid that made me go “Oh, SHIT!”

#10: The opening moment of the Drug Lab fight scene. This is the pivotal moment at the end of the second act when the three surviving cops reclaim the initiative and go on the offensive against Tama. Where the action up until this point has been all about disempowering the cops, their numbers being winnowed down by the bad guys, always having to fight on the back foot, there’s a feeling of fierce joy at this turning of the tables, the hero and his mates finally being able to take the fight to the enemy on their own terms.

The Drug Lab is the most straightforwardly cathartic and fun of the film’s six big action beats, not coloured by horror elements the way the previous ones were. Each of the three cops get a series of wince-inducing finishing moves in quick succession, and there’s a sense that they’re taking out their frustration and anger at their situation on some unsuspecting skulls. The scene is set by a lateral tracking shot of the lab, an open space full of long steel tables and cabinets, full of drug cooks just going about their business, apparently oblivious to everything that’s been happening on the other floors. Dagu enters the room at a full sprint, body checking a sentry through a stack of barrels, announcing his presence with a wordless battle cry right as the main motif bursts in on the soundtrack. Glorious.

#9: This is kind of two “Oh, SHIT!” moments, but they happen in immediate succession, so I’m counting them as one. During the opening firefight, the SWAT team barricade themselves inside an apartment on the sixth floor. Cornered by snipers covering the window and with the mob outside breaking down the door, they hit upon the idea of breaking through the floor with a fire axe and dropping down to the storey below as a short-term avenue of escape.

Jaka, being the kind of guy to lead from the front, is the first to drop through the hole… but upon landing, he’s immediately jumped in the lower apartment by three more goons who must have been waiting for him. Rama and Bowo jump down to his rescue; Rama drags the first of the three attackers off of Jaka, shoots him, and fends off the other men in the room with his assault rifle. The first “Oh, SHIT!” beat comes a moment later, when Bowo buries the head of the fire axe in the shoulder of the second guy on top of Jaka. You’d think that would probably be enough by itself to hinder further aggression, but Bowo disagrees. He hoists the mook off of Jaka, and then delivers the coup de grace: a second axe blow, cleaving through the guy’s sternum.

Before the viewer can even process the insane overkill of that, we get the second “Oh, SHIT!” beat immediately after; Jaka, left with only one skinny criminal on top of him, overpowers him, draws his sidearm and, without blinking, shoots his assailant three times in the temple at point-blank range. This is The Raid truly starting as it means to continue.

#8: The final beat of the corridor fight on the seventh floor, when Rama deflects a series of blows from the last guy to try to fight him, grabs him by the ear, and smashes his head against a light fixture, shattering it. That alone probably knocked the guy out, but as his opponent slumps to the ground, Rama mashes his head repeatedly against the wall, breaking tiles as he falls; better safe than sorry. A trailer-ready moment if ever there was one.

What’s especially striking about this moment is all the behind-the-scenes technique that went into making it happen. This particular section of wall, and this particular light fixture, which look indistinguishable from the others in the same frame, were swapped out for stunt-safe props. The glass was breakaway glass; the tiles and the wall behind them were padded with sponge. The blood we see in the spots where the mook’s head impacts is from squibs concealed in his long mane of hair, and the sounds of bone colliding with ceramic were all added into the sound-design in post-production. The way these elements come together to create the impression of a man being concussed, and maybe killed, is extraordinarily persuasive. It’s Movie Magic in the low-down, analogue sense, generating what looks like spontaneous, vicious violence from carefully planned safety.

#7: The fridge explosion. With all the surviving cops pinned down inside a small apartment, several of their number injured, the windows covered by snipers and a horde they can’t hope to repel breaking down the door, Rama thinks on his feet. He rips a gas canister out of the kitchen’s cupboard, places it in the refrigerator, and with the help of Dagu and Alee (Alee gets killed in the process; RIP), he places the fridge against the door, throws in a hand grenade after the gas canister, and uses the whole contraption as an IED that incinerates the attackers coming after them on the sixth floor in a colossal fireball. The first act ends in style, with Rama comprehensively proving himself a capable and resourceful protagonist.

#6: The first beat of the corridor fight on the seventh floor, the first real hand-to-hand exchange of the movie after the initial gunfight uses up, apparently, all the ammunition in the building. Rama is swarmed by attackers coming at him from every door in the whole corridor, and he fends them off with a combination of knife and baton techniques while trying to keep the injured Bowo out of harm’s way. The first guy Rama dispatches quite perfunctorily; baton to the face, knife to the back of the knee, we don’t really see anything.

The second attacker, though, is the one that makes an impression. The guy lunges at Rama out of door 713, wielding a cudgel. In viper-quick succession, Rama deflects the blow, suspends the guy’s right leg with the baton, and plunges his serrated combat knife up to the hilt in the dude’s flesh, just below the pelvis. If that wasn’t enough, we get a close, loving insert shot of Rama ripping the knife down the length of the guy’s thigh before wrenching it loose at the kneecap, certainly ensuring his opponent will never walk again, if he doesn’t die from massive blood loss in the next couple of minutes.

If the preceding siege sequence didn’t get the point across, this moment does. “This is The Raid,” it says. “Our heroes are not nice people, and they don’t fuck around.”

#5: The opening frames of Mad Dog’s terrifying fight with Jaka. It comes after a minute or so of discomfiting stillness; Mad Dog has Jaka a gunpoint, dead to rights, so why doesn’t he pull the trigger? Mad Dog gives us his soliloquy about his relationship with violence. “I’ve never really liked using these,” he says, as he ejects the magazine from his gun. “Takes away the rush. Squeezing a trigger? It’s like ordering takeout.” Which is just an amazing, iconic line to give to an out-and-proud violent psychopath.

Even so, when he squares off with Jaka, unarmed, looking completely calm and collected as he does so, you’re compelled to wonder why Tama’s heavy is putting himself at such a disadvantage. Yayan Ruhian is about half Joe Taslim’s size; the two of them look comical standing opposite one another in the frame, David and Goliath.

Or at least, they look absurd, right up until the moment Mad Dog moves, bursting into action with explosive speed unmatched by anything we’ve seen in the film up to this point, immediately putting Jaka on a back foot that, despite valiant effort, he can’t recover from. Characters have spoken about Mad Dog up until now in tones of dread; this is the point where he proves the rumours true.

#4: When Rama and an injured Bowo take refuge in Room 726, the apartment belonging to the one sympathetic resident of the building, they hide from the Machete Gang in a narrow, hollow space inside a false wall. The Machete Gang show up and begin trashing the apartment in their search for the cops; to this end, their leader (Alfridus Godfred, in a performance memorable for his protruding, unblinking eyes alone) stabs his signature rusty blade repeatedly through the false wall, working his way from left to right, looking for the telltale resistance of human flesh. With the final stab, he leaves the machete embedded in the wall… and also in Rama’s left cheek, behind it.

This is the film’s one great set-piece that can’t really be described as an “action scene;” it’s a sequence of pure suspense, and by the time Rama is sitting with a rusty blade in his face, trying desperately not to make a sound lest he get innocent parties killed, the tension has been ratcheted to unbearable levels. The wound remains open and bleeding for the rest of the film, and remains as a scar in The Raid 2, an unforced bit of continuity I always appreciated.

#3: Rama is cornered on the seventh floor by the Machete Gang. Grappling with one of their members, he stumbles through a door onto the stairwell where, in slow motion, he throws the Machete Ganger over the railing. You expect the guy to fall into the black pit beneath, but no; his onscreen fate is much worse. The film cuts back to real-time, and he sails all the way across the gap, turning head over heels, to land on the railing of the opposite mezzanine a storey below, the impact neatly snapping his spine.

The sight of stuntman Rully Santoso having his body folded unnaturally in half, the way you might break a Pringle across its widthways axis, is so visceral that for years, I was convinced that it was achieved by a CGI body-double (despite how far out of The Raid’s budget an effect like that reasonably would have been). Turns out, no: it was a composite shot, stitched together from three separate takes and a fixed camera angle.

It’s a moment that’s added a little extra frisson when you learn that this stunt went badly wrong. There was an accident with the wire rig meant to guide Santoso safely down to the crash mats at the bottom of the stairwell; instead, he fell fifteen feet onto a hard, concrete surface. This man almost died for the sake of this punchline, so you’d better goddamn well appreciate the moment’s magnificence.

#2: The doorframe scene; possibly the most infamous moment in the film. Rama, in the thick of his corridor fight on the eighth floor against the four surviving members of the Machete Gang, breaks down one of the flimsy wooden apartment doors. Moments later, grappling with the gang member in the red shirt, he launches both himself and his opponent back into the open room, and brings down the gang member’s neck on the jagged, splintered remains of the door, killing him instantly.

It’s the suddenness of it that gets you. This is Gareth Evans’ particular brand of genius, what he does better than maybe any other filmmaker alive. The scene up to this point is clearly building to something, the rhythm of the action accelerating, the cutting getting faster, the score rising to a crescendo – we’ve been primed to expect a moment of release, but when that moment comes, it’s just a half-step grislier and nastier than the sequence had been up to that point. It recombines elements of the mise-en-scene already planted in the viewer’s unconscious understanding of the geography in a surprising, ingenious way. And it’s an upward gear-shift; blows have been exchanged so far in this fight, but now, real up-close-and-personal death is on the cards. It’s the act-break in the fight’s two-act micro-narrative, letting us know that the stakes are raised for the second half.

…we’ve been primed to expect a moment of release, but when that moment comes, it’s just a half-step grislier and nastier than the sequence had been up to that point.

An element I particularly love about this moment is how it cuts right after to Rama’s face, inches away from the face of the man he just half-decapitated; the music drops out, and it holds there for a couple of seconds, giving us a good view of Uwais’s stricken, sickened expression. The unspoken implication is that he’s as thrown by this sudden escalation as the viewer; this enormously brutal kill isn’t something he chose to do, at least not consciously; it just happened in the heat of the moment. He recoils from the life he just snuffed out, visibly gathering himself, before the remaining three Machete Gangers pour into the apartment after him, and the fight resumes. Therapy will have to wait.

This is extraordinarily well-considered visual storytelling, every single technique at the film’s disposal coming together for a moment you’ll see on the inside of your eyelids for days afterwards. And yet it’s still not The Raid’s most memorable beat.

#1: The climax of the final fight, where Mad Dog fights Andi and Rama simultaneously, and has seemingly beaten them both. He gets Rama in a chokehold from behind and begins to slowly strangle him, savouring his victory, echoing the way he previously finished Jaka. While the villain is distracted, Andi musters up the strength to get back to his feet, creeps up behind him, and stabs him in the neck with a broken fluorescent light-tube. Mad Dog, for a couple of seconds, buckles in pain and shock…

…And then resumes beating the shit out of Andi, the light-tube still embedded where Andi plunged it. Pouring blood from the world’s most badly botched tracheotomy, he fights harder than ever against the brothers for a full minute of screentime, and almost wins. It takes Rama breaking his arms, his back, and dragging the shattered glass across his throat to finally finish him with a horrific, rattling death-gurgle.

This might be my favourite single beat, not just in The Raid, but any action film, ever. It’s the perfect crescendo to the film’s symphony, absurd in the best possible way. In that moment, the viewer is poised right at the outermost edge of their suspension of disbelief. “No,” is your first thought; “that’s impossible. He cannot possibly keep fighting with a wound like that.” But then, there’s doubt. The entire film up to this point has incrementally primed you to expect human bodies being pushed past reasonable, physically plausible limits. And this is Mad Dog, and Yayan Ruhian’s performance thereof. “Maybe,” you think, “just maybe this guy really is some kind of indestructible demon.” That doubt persists for just shy of a minute, your knuckles bone-white against the armrest, and that minute is an inimitable, once-in-a-generation moment of cinematic magic.

I’ve been chasing that high ever since.

If The Raid isn’t the greatest action movie ever made (and, to put my cards on the table, I don’t think it is, but it’s in the conversation. Probably Top 5), it’s most certainly the purest. It’s the action film that uses the language of its genre to communicate with its audience most unadulteratedly, and most successfully. Seeing it for the first time in 2012, in a packed cinema, with an audience that winced and cringed and cheered at all the right moments, was one of the most euphoric moments of my moviegoing life, and I’ve followed Gareth Evans’ career with nigh-religious zeal ever since, hoping that he might one day make something to match or surpass that rush.

It’s the action film that uses the language of its genre to communicate with its audience most unadulteratedly, and most successfully.

*(Some housekeeping, before we go: multiple versions of The Raid exist in the wild. The version I’m most familiar with is the version most widely distributed internationally, which we can term the US cut. The US cut, not the International cut, because it contains edits made specifically at the behest of the MPAA, in order not to be hit with an NC-17 rating that would have made theatrical distribution in America unviable.

The differences between the R-rated version and the uncut version are contained to two scenes, and amount to barely ten seconds of footage. In the scene where Tama is executing prisoners in his office, we see the fourth guy in the lineup get shot in closeup. And in the scene where Andi dispatches the two goons in the elevator, there’s an extra shot of him withdrawing the knife from the second goon’s neck. Honestly, the difference between the two versions is so minimal as to be virtually imperceptible; having seen both versions, I was looking for the changes, and knew what to look for, and I still barely noticed. The handful of censored frames do nothing whatsoever to soften the film’s content, and frankly, they smell of an arbitrary concession to the dinosaurs in the MPAA to reassure them that they’re doing meaningful work.

Much more significant, however, is that there are two different scores for The Raid. The Shinoda/Trapanese soundtrack was commissioned by Sony after the distribution rights to the film were sold to Sony Pictures Classics during its production, and it replaces the score used when Merantau Films distributed the film in Indonesia, composed by Aria Prayogi and Fajar Yuskemal. Regrettably, though I’ve seen The Raid with those cut 10 seconds of footage restored, I have not seen it with the Prayogi/Yuskemal score. From what I’ve heard of it, it’s quite a different beast from Shinoda and Trapanese’s take.

I honestly like the Shinoda/Trapanese version of the score; sure, it was definitely conceived as a cross-promotional marketing stunt, giving a big-shot rock star a chance to add “composer” to his multi-hyphenate status, and giving the film a publicity boost from attentive Linkin Park fans. But, judging from the BTS footage, Shinoda genuinely seems to have approached the project diligently and with unfeigned enthusiasm for the film, and the end result that he and Trapanese produced stands on its own merits. It feels like a part of the whole, complementing The Raid’s atmosphere and forging its own distinct sonic identity.

I just wish that the very good score we got didn’t come at the expense of another reputedly very good score that we were denied. #ReleaseThePrayogi/YuskemalCut, please)

Is It Good?

Masterpiece: Tour De Good (8/8)

Awards, Honors, & Rankings

Andrew is a 2012 graduate of the University of Dundee, with an MA in English and Politics. He spent a lot of time at Uni watching decadently nerdy movies with his pals, and decided that would be his identity moving forward. He awards an extra point on The Goods ranking scale to any film featuring robots or martial arts. He also dabbles in writing fiction, which is assuredly lousy with robots and martial arts.