Mirror mirror on the wall

Good Lord. What a film.

Sometimes, that’s the only reaction that feels appropriate to a piece of cinema: sheer admiration for the chutzpah, for the overwhelming wholeness and muchness of what you just watched. There is no one route into thinking or talking about The Substance because it is so big and enveloping. Everything happens so much.

That’s maybe an overstated reaction to what could be called “Margaret Qualley’s Butt: The Movie” or “The Two Hour Countdown to the Blood Hose,” but The Substance earns it. It’s a piece of unrestrained maximalism, and it uses that maximalism with precision. Where films like Barbie or Beau Is Afraid sometimes mistake bloat and theatricality for a grand artistic statement, The Substance actually hones its chaos into a unified statement.

What surprises me is how focused this film is, especially given its 141-minute runtime. Normally, when I see a horror film clocking in past two hours, I assume the director fell in love with the footage and forgot the delete key exists. But director-writer Coralie Fargeat gives the entire length real shape and purpose. The film is huge in a way I’ve not quite seen before: not overlong in plot, nor padded between meaningful narrative beats. Instead, Fargeat inflates every individual story beat to the most explosive and outrageous version of itself — visually, emotionally, physically. Her goal is to make every scene be The Scene, that tipping point most great films have and crescendo towards. Except here, every few minutes is a climax, one you assume can’t be topped until the bar is raised again a scene or two later.

The film is a Hollywood Jekyll-Hyde riff: fading celebrity Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) undergoes an experimental procedure involving a mysterious green goo — the titular substance — that generates a second body for herself, this one younger and more perfect. This Elisabeth 2.0, undetected as the same person by the outside world, takes the name Sue (Margaret Qualley). The one rule is that Elisabeth/Sue must alternate bodies every seven days. Her consciousness switches between vessels. She is the same person with each switch — or, rather, the same consciousness, the same soul. Exploring the extent to which our body is inseparable from our identity is part of the film’s consideration. Elisabeth and Sue’s respective relationships with the world and every person in it is so different she may as well not be the same “person.” But the thrust of the film’s conflict comes from the switch’s limitations: So long as she always remembers not to stay in Sue’s tantalizing, perfect body for even a minute longer than one week, she’ll be able to maintain her two forms indefinitely.

Reader, do you think she might test that limitation of one week before the runtime is through?

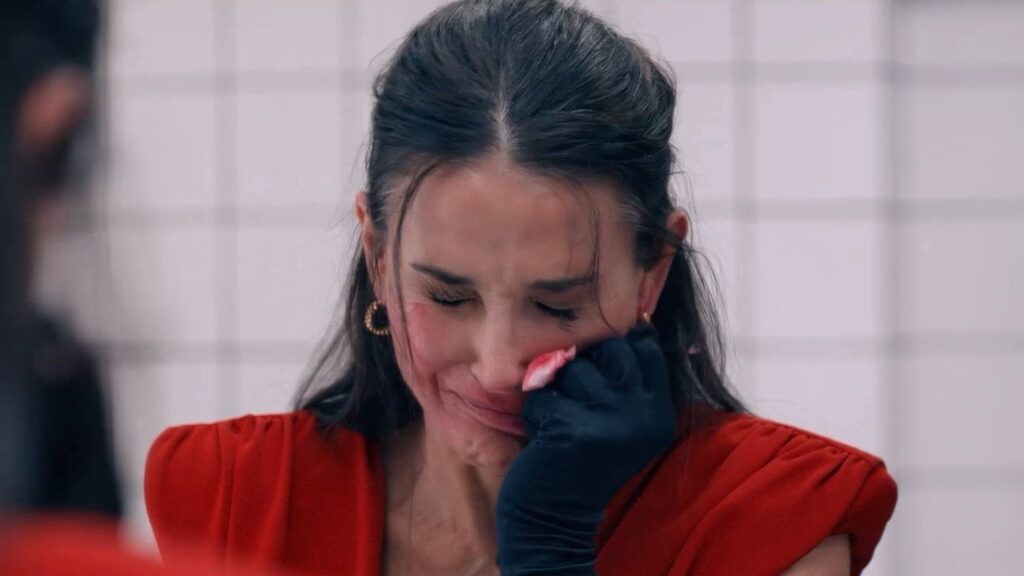

The Substance is as much a feature-length panic attack as it is an investigation of bodily decay and self-image. The aesthetic draws from Cronenbergian body horror, but it’s glossier, more music video-adjacent, and almost erotic in its examination of a deteriorating human body. The final act turns into a full-on blood rave, but even early on, the film lingers on the female form with alternating lust and horror — the gentle wrinkles of middle age vs. the firm smoothness of youth, Sue emerging from Elisabeth like an inverse butterfly.

The scenario is drowning in irony and self-contradiction, all of which is shaped into a potent critique of Hollywood. “Remember: You Are One” reads one of the warning cards, yet Sue and Elisabeth refuse to see the other as themselves until it’s too late and they have no choice. Something Monstro this way comes. But even at the beginning, the scenario is almost self-evidently ridiculous: Elisabeth is only turning 50, and Demi Moore (aged 62 but easily passing as 50) is extremely beautiful, aging gracefully. This is the point, of course: The Hollywood system, a cipher for society writ large, is quick to reject and dispose of any woman showing the first sign of being over the hill. This is exemplified by Dennis Quaid’s grotesque turn as the producer named Harvey (hmmm… can we think of any notable producers named Harvey?). As much blood as The Substance spills by its finale, nothing in this film is grosser than Quaid slurping and chewing on shrimp for lunch.

This setup and horrifying execution are an extension of the feminist filmmaking philosophy outlined by Fargeat in Revenge. Her tack is not subversion of gaze, but reclamation of it. Sex-as-empowerment is a bit of a cliche, and in cinema it almost instantly turns exploitative. Yet Fargeat finds a way to worship the female body (Qualley’s especially) in all its glory without making external sexual gratification the purpose of that worship.

The film is brutally funny, too, in that very specific French way where the nasty decadence and repulsion provoke the uncomfortable laughs. There’s touches of Terry Gilliam’s bleak absurdity in this bizarre version of Hollywood — part futuristic dystopia, part ‘80s cocaine neon glitz where the biggest star in the planet makes aerobics videos like Jane Fonda. But most of the laughs come from the shock of the film pushing its scenarios to their outer, most outrageous limits: Elisabeth’s decaying form increasingly resembling the old hag from Snow White; Margaret Qualley’s uncomfortable, much-memed smile when certain bones have exited her body.

It helps that The Substance is anchored by two fearless performances. Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley shoulder nearly the entire film’s weight. Calling it a two-hander would be wrong: the pair rarely appear in the same scene, never exchanging dialogue. It’s a one-woman show split in two, each actress throwing the entireties of their own bodies into their performances. Qualley really astonishes: the film worships her body and allure (right until it doesn’t), and she owns it. Her experience as a dancer shines; there’s a grace in even the most zoomed-in, slow-mo observations of her form and motion.

Moore is a revelation, though; I haven’t seen anywhere near all of her performances, but if this isn’t her career peak performance, I’ll be blown away. She exhibits no self-protection, no hiding from the most piercing and critical gazes. Moore has one scene involving putting on makeup for a date that might be the best piece of acting of 2024. She absolutely drills the ups and downs (mostly downs) of her second life here.

(One more shout out to Qualley: Despite natural beauty and the obvious access to high-profile opportunities as the daughter of Andie MacDowell, she has forged a risk-taking career for a while now, working with auteurs and women and emerging talents — Claire Denis, Yorgos Lanthimos, Margaret Betts, and more. Every night I pray that she will leverage her financial privilege by steering away from IP slop. If she keeps it up and remains adaptable, I wouldn’t be surprised if she stays in awards conversations for years and years to come.)

But the true star of The Substance is Coralie Fargeat, whose command of tone, texture, and terror marks her as a capital-V Visionary. Her touch on every aspect of the production is palpable: the oily pinks and sickly greens of the color palette; the rhythmic, over-the-top cadence of the imagery; the tactility and disgusting heft of every prop and piece of prosthetic makeup. Fargeat embraces practical effects with an almost fetishistic fervor, not as throwback but as means to maximizing texture. It’s all about making the human body feel real even as it is mutilated in inventive, speculative ways — fleshy and bloody and painfully present. The film’s scale feels impossibly big for its $18 million budget, yet also weirdly handmade, like every patch of hair, sequins, and viscera was personally crafted.

Much of that tactility comes from the film’s no-holds-barred production ethos. The 108-day shoot was arduous. Prosthetics were sculpted to the level of visible pores and individual veins; Moore and Qualley were regularly submerged in glue and silicone for hours at a time. Fargeat and her team had to build many of their own sets due both to Fargeat’s unique vision and the strain (and red stain) each set would undergo. The team used a literal fire hose for the climactic New Year’s Eve scene (though it wasn’t pumping clear water).

That climax deserves its own shrine. I won’t spoil it, as it is a bewildering experience to see it unfold in real time, but it’s one of the great final acts of any film I’ve seen. It’s grotesque to the point of hilarity. You keep thinking it’s over, there’s no way this can get any grosser, and then it pushes just a little further into baroque desecration. There Will Be Blood (and breast).

I won’t pretend The Substance is subtle. It doesn’t whisper its themes. The film, like Fargeat, is a provocateur — impish, even bratty, in how proudly it rubs your face in its excesses. What saves it from transgressive show-off nastiness or feminist TED Talk is both the totality of its commitment and the euphoria (rather than depravity) of its execution. This is a film that is so fully invested in its absurdity and ornamentation that it completely sucks you in. It also presents in its extremity a catharsis, and with that a dim, flickering sense of hope for avoiding the agony of this fairy tale. Its critique of image culture and patriarchal rot is not nuanced or rich — but it doesn’t need to be when it’s this visceral. Some truths are so obvious and well-understood that they only leave an impact if they are shouted nude and at full volume.

Cinema is, after all, a sensory medium first and a literary one second. And The Substance is pure cinema — a nauseating, breathtaking, one-of-a-kind system shock. It doesn’t just depict transformation; it is transformation itself, of cinema to a higher form. I am stopping just short of calling The Substance a full “Tour de Good” Masterpiece, but I’ve debated it for months and I still might change my mind. It’s my favorite film of 2024 and one of the most singular works I’ve reviewed since kicking off The Goods in 2020. Like its monstrous anti-heroine(s?), it draws you in with glamour and grows darker the deeper you cut. Good Lord. What a film.

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Awards, Honors, & Rankings

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Picture (Winner)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Director (Winner)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Sound (Winner)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Actress (Demi Moore) (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Actress (Margaret Qualley) (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Editing (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Scene (New Year's Eve) (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Screenplay (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Cinematography (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Visual Effects (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Costuming (Nominee)

- The B.A.D.S. (2024) - Best Production Design (Nominee)

- Top 10 Movies of 2024 - #1

- Favorites of the First Half of the 2020s

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

2 replies on “The Substance (2024)”

Amen.

Enough ink has been spilled gushing about The Substance in the last few months, but I’d add one point that I haven’t seen made all that often: it’s a rare horror movie that I actually found *scary.* Or at least, a certain type of scary – the awful, gnawing, empathetic dread of seeing someone progressively trapped by their own decisions, so acute that I found it tough to watch at times.

The inescapability of Sue’s decisions upon Elisabeth is pretty harrowing, and played SO well by Moore. I love it.