There are no two words in the English language more exciting than "Damien Chazelle"

The idiom “tight as a drum” refers to the tension of a piece of leather on the frame of a drumhead. To produce any resonance, the skin needs to be completely taut and even. I thought of this phrase frequently as I watched Whiplash for the first time. It is a movie that feels “tight as a drum” during the majority of its runtime (more thoughts on the shambling conclusion in a moment). It is as laser-focused on its story and themes as Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller) is with becoming a great jazz drummer.

Whiplash is Damien Chazelle’s first widely released film as director and second feature-length film overall, following the student film he made while enrolled in Harvard, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench. It is an expansion of a short that premiered at the 2013 Sundance Festival and earned enough buzz to get Chazelle full funding to make a feature. It subsequently became a profitable indie hit for Blumhouse (earning almost $50 million against a $3 million budget), a critical darling, and an awards season favorite. Whiplash was nominated for 5 Oscars, including Best Picture, and won three of them — Editing, Sound Mixing, and Best Supporting Actor for JK Simmons.

But Whiplash casts a longer shadow than just picking up some hardware. It is to millennials what Reservoir Dogs and A Few Good Men were to the previous generation: an addictive, world-class, white-dudes-shouting chamber drama that becomes an infinitely-rewatched, word-of-mouth marker of movie fandom for all types. It announces Chazelle as a special talent and visionary — or perhaps “audio-visionary” is more appropriate. It is an acknowledgment of the cost of greatness in a creative pursuit. And while I don’t agree with the insinuation of its conclusion that a few select great ones can and must sacrifice their humanity to make great art — I’m not entirely convinced that Chazelle himself believes it, for that matter — it absolutely delivers its statement with the force of a mallet and the resonance of a gong.

Neiman is a student at an elite music college, and he dreams of joining the even-more-elite jazz band run by Terrence Fletcher (JK Simmons). He finally gets that chance, only to learn right away just how cruel and manipulative Fletcher is as a conductor and teacher. The scene of the first rehearsal — which is also the focus of the rough-draft short — is the best in the film, a knife in the gut that keeps twisting as Neiman is further and further humiliated.

It’s this first rehearsal scene that the movie’s true purpose emerges: A rage-a-thon act-off between Teller and Simmons, each one-upping the other time and again. Simmons is downright horrifying as a perfectionist task-master with sadistic tendencies. If you’ve ever had a nasty teacher, Whiplash will bring out the traumatizing discomfort of that experience from your deepest memory wells. His tongue is so dexterous, his presence so intimidating, his reflexes so sharp that his ferocity almost hops off the screen. Simmons won an Oscar for the role, and I do nut begrudge him for it a single iota.

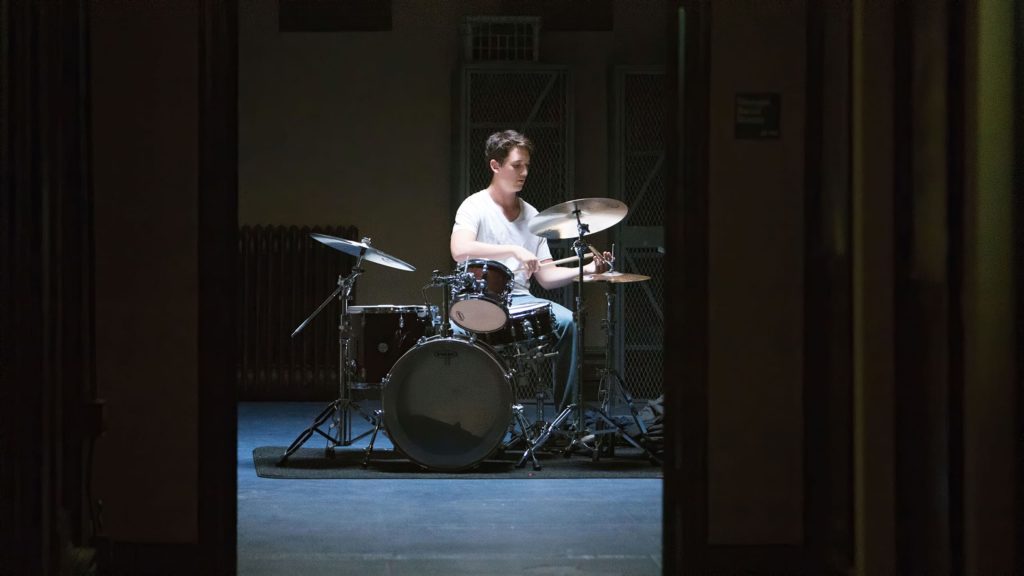

Against all odds, I think Teller might be even better: For one, he is very plausibly a drumming-obsessed prodigy. And his blend of stubbornness and bubbling anxiety is terrific: He starts with a run-of-the-mill haughtiness that’s common among college freshmen; it slowly morphs into demonic possession exorcised on the drum kit. Neither Simmons nor Teller hold back on the physicality of their roles, but this is especially evident in Teller’s performance. The way he can, e.g. take a slap full-on to the face, or sweat and pant through a long-take drum solo, is visceral method shit.

The movie takes a turn at the break between the second and third act. I’m going to openly discuss the ending from here on out, so please click away now if you don’t want to read any spoilers.

Neiman continues his fraught success throughout the middle act of the film, but it’s curdled with toxicity. It’s almost the opposite of the classic inspiring teacher dramas like Stand and Deliver: Rather than the education unlocking some inner dignity for the students, Neiman’s success makes him more monstrous. The hunger for perfection, for musical transcendence, was always there as a seed, but Fletcher has grabbed hold of it and weeded out whatever kernels of empathy and compassion and balance lingered. (Fletcher and Mr. Burns would get get along, I think). Neiman turns against his family and his girlfriend and everything else in his life that made him human to pursue drumming — i.e. to please Fletcher.

That’s what makes the car crash around the 65-minute mark so powerful for me. It certainly pushes the film into the territory of fantasy, or at least metaphoric surreality (see Chazelle’s script for Grand Piano for an even more extreme example of a musician suffering an outlandish cruelty). It takes Neiman’s willingness to sacrifice everything, even his flesh and bones, and escalates it to its theoretical endpoint.

The final act of the film is the most fascinating part of the film, though the least cohesive. It is certainly the most narratively slack. Rather than the relentless energy of the opening two thirds, Chazelle pulls on the story reins to sort through his competing thoughts about the expensive self-sacrifice in achieving greatness. Neiman rats out Fletcher as an abuser but still seems, under the surface, to revere him as a deity. He curses and worships his master like a burdened disciple. When they bump into each other at a bar, Fletcher gives a monologue in which he narrates the themes of the film, at least from his own twisted perspective. Normally, I roll my eyes at this kind of writing, but it leads to such a fantastical (and fantastic) conclusion, that I barely care here.

The very final scene is an all-out bit of bravura from Chazelle. It would have been one thing to pay lip service to musical greatness and never depict it, but in the epochal drum solo of the finale, Chazelle actually convinces us that Neiman has transmuted the ordinary into the sublime. You’d think it would be boring to stare at a guy sitting in a drum kit for ten minutes, yet it’s the opposite. This final scene is masterpiece stuff, conveying as operatic drama and epic action, the drumming shot from all angles, sweat glaring off Neiman’s skin and the snare, lights flickering as if Neiman is Apollo carrying the sun with each beat. Neiman’s face grimaces in pain as Fletcher guides him to ecstasy. The movie cuts to credits at the perfect moment, too; before we hear the crowd’s reaction: Unlike most movies about performing artists, Whiplash is completely unconcerned with the notion of the audience’s rapturous reception. There’s an audience of one for all the musicians in this movie, and it’s Fletcher, the gatekeeper of immortality — equal parts St. Peter and Charon. It’s through him, not a cheering crowd, that musical divinity is achieved.

As much as I love the ending as a piece of spectacle and filmmaking, it’s a blatant a U-turn on the movie’s perspective. Up until that final scene the film had been, at least textually, critical of Fletcher’s “no pain no gain” bullshit, though Neiman’s lethargy after his car crash at least suggested he felt empty outside the pressure cooker. A cynical read of the film might see the finale as an endorsement of savage educational practices and self-immolation. Indeed, Fletcher’s enlightenment-via-torture seems to work in the long run as Neiman sheds his coil of “good job” and reaches a higher plane in that final scene.

Yet the overall feeling the conclusion captures is one of intense ambivalence: It accepts that there are masochistic weirdos like Neiman who have a void they can fill only with a grueling regimen and outrageous standards, and that there are indeed cruel leaders like Fletcher willing to exploit them in the hopes that they can squeeze out something miraculous. Accepting the existence of something is not an endorsement, and so much in the movie points out how destructive this is. Dynamite is dangerous, but there sure is something awe-inspiring about watching it blow, huh?

In other words, I view it similar to how I view the ending to The ‘Burbs: I don’t hate it because it refuses align with the arc and messaging that led it there. In fact, its perpendicular turn makes it that much more interesting and beguiling and chaotic.

My biggest actual complaint about the ending — and in this case I mean the entire third act — is that it doesn’t jolt into a new storytelling gear hard enough. If the point is that Neiman has received both a literal and metaphorical blow to the head in his car crash, including a subsequent implosion of his drumming career, then I wish the filmmaking would have been even more elliptical and hallucinatory. It’s a rattled coma rather than a delirious haze, when the latter would support the subjectivity of the final few scenes much more. (Put another way: Let me debate whether Neiman died during the car crash and the rest of the movie is his purgatory before crossing to Heaven/Hell with the “Caravan” solo, Chazelle!)

One important piece of Whiplash’s presentation is the terrific music. Many films centered around musicians do not contain anything that sounds even a little bit like actual live music. So often it is clearly piped in during post-production, and you can feel the absence of that spark that exists when real musicians are performing. But all of Chazelle’s films place an emphasis on real music that pops — it always feels like you’re sitting in a room watching one of the best jazz bands in the country. Whether the music was recorded live or touched up at all, I’m not sure, but the sense of immersion is incredible.

This is especially true of Teller’s performance as Neiman. I never doubted for a second that Neiman is a genuine talent. One thing I’ve always admired about Chazelle’s filmmaking is the way his talented cast seems invested in the music as the story and seem to be doing all the playing themselves. (See also: Seb in La La Land.)

Justin Hurwitz provides the music, as always in a Chazelle picture. He provides an excellent, jazzy score and composes a few numbers. But the film is dominated by two jazz standards more than any of Hurwitz’s compositions: Those two songs are the titular “Whiplash” by Hank Levy and “Caravan” by Duke Ellington, the latter which makes up the remarkable final scene.

The film is shot by Sharone Meir, whose career beyond Whiplash is rather undistinguished. But I think his work here is terrific: The yellow-gold hue of the performance scenes is both inviting and slightly acidic. Meir also adds a chilliness to the majority of the scenes off the stage as Neiman’s life plunges into icy obsession.

Whiplash is one of the best wide-release debut films of the century to date. (That excludes Chazelle’s student film, his short, and his two screenplays for this accounting.) It’s not only a gripping drama and an outstanding demonstration of technique, but a manifesto for the main theme that Chazelle is still exploring to this day: obsessive performance as the rope in an eternal tug of war between self-actualization and self-destruction.

- Review Series: Damien Chazelle

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.