Would you be mine? Could you be mine?

It’s not often you can honestly describe a film as both “exploitative” and “restrained,” but The Perfect Neighbor lives in an unsettling overlap — and gets a lot of its magnetic power from the fact that it pushes past tasteful boundaries in some areas pulls back in others.

The scenario is simple and horrifying in a classic American spirit: a racially-charged neighborhood dispute in Florida escalates, again and again, until it becomes fatal. The film traces the lead-up to the murder in a brutally chronological fashion — bickering neighbors, police visits, increasing hostility — and it does so with almost no traditional documentary scaffolding. No sit-down talking heads to explain what happened to the audience. No narrator stepping in to explain how you’re supposed to feel.

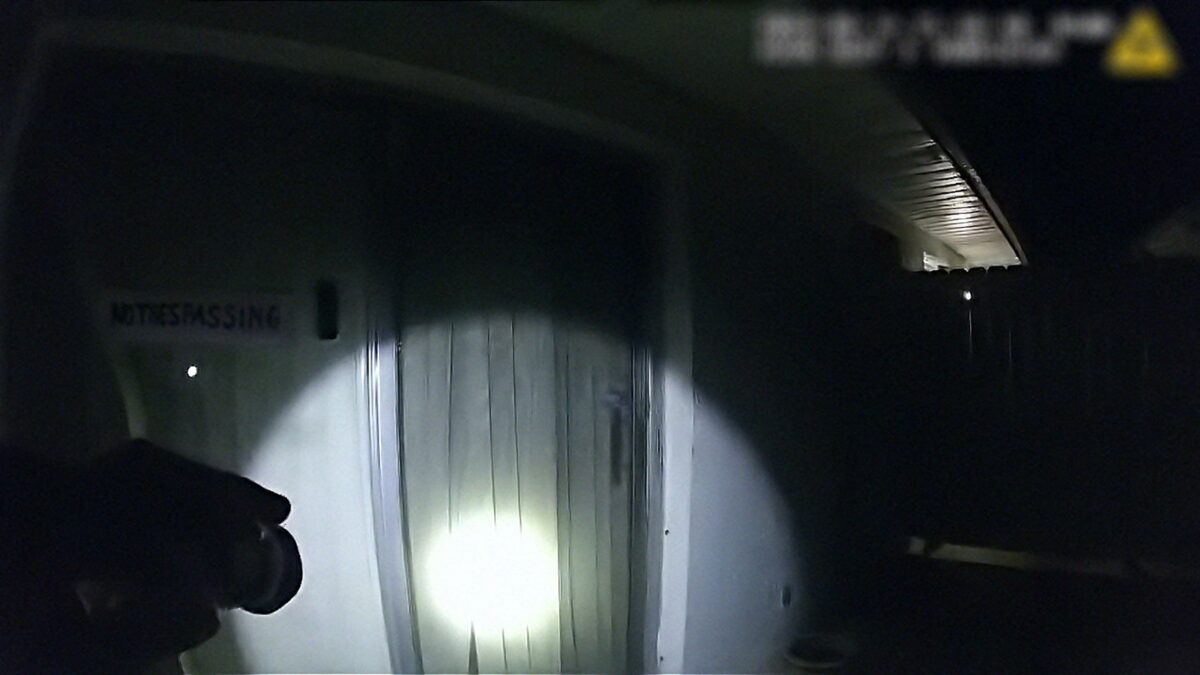

The Perfect Neighbor is, instead, just footage. It’s built almost entirely out of police bodycam and dashcam video, plus omnipresent angles from electronic doorbells and smart-home cameras. The lack of “voice” of the footage is part of what makes it so gutting: fixed, impersonal, and yet still intimate like we’re a fly on the wall of scenes we were not meant to witness. The movie’s most distinctive formal choice is that it commits to this style of footage so fully. The lightly filtered reality builds into a clear, crushing story in what feels like real time. It’s not cinematic, exactly. It’s almost anti-cinematic in some ways, with production values of a 2010’s low-budget found footage film. And yet it sucks the air out of your lungs.

That relentless presence of footage is also where the feeling of intrusion, bordering on exploitation, creeps in. In addition to the slow buildup and police activity surrounding the shooting, we also see its painful aftermath. The Perfect Neighbor includes moments so raw they seem to be a violation of dignity: We witness the moment of A.J. Owens’ murder (body and blood blurred out, but nothing else). In the film’s most harrowing section, we see the rippling impact on her children as they learn what happened and try to understand that their mother is not coming back home. It’s one of the most searing and sickening things you’ll ever see, and I can’t entirely square whether the world is better off that these moments have been captured and shared. I both resent and admire the commitment of director Geeta Gandbhir, a Peabody-winning and Emmy-winning (possibly soon to be Oscar-winning) documentarian, in refusing to hold back and showing us what gun violence really does to people.

What keeps The Perfect Neighbor from feeling purely sensationalist and in poor taste is how disciplined it is about letting the pattern of incidents speak for themselves, but still pointing the audience towards something to rally around. Without ever turning didactic, the film builds a case that normalized, everyday racism is more toxic and unavoidable for Black people than we might pray for. It shows the reckless volatility of widespread firearm ownership and the idiotic illogic of stand-your-ground laws… not as abstract policy debates, but as a lived, gut-churning, escalating reality in a way fiction never can.

A huge amount of credit goes to editor Viridiana Lieberman, because “found footage” without an organizing intelligence and flow is just a headache. Here, the evidentiary sprawl becomes a legible, devastating narrative that, sick as I feel saying it, rivals the pacing of a scripted thriller: A gnawing sense of impending doom and building suspense leading to an inescapable turning point from which there’s no return. It’s an extremely effective edit, and will be on my shortlist of the best of the year.

Gandbhir also exhibits some restraint in getting carried away with a call to action that must have been the temptation when telling this gutting story. The film’s “argument” mostly arrives in the negative space: Gandbhir does not explicitly editorialize until the closing frames, which forces you to sit with the footage and ponder it: what all this says about its subject, what the subtext (does that word apply to real life?) of every event is. The general absence of commentary isn’t neutrality, of course; the film is unabashedly anti-gun, or at least anti-“stand your ground”. In the closing moments, the film finally steps outside its observational posture: a late title card contextualizes the legal and moral fallout in a way that emphasizes the scope of which these laws and moral standards normalize suffering.

All of this makes the Netflix version’s opening choice all the more frustrating. Starting with a “cold open,” preview footage that jumps ahead toward the emotional/violent center, feels like a “hook” for attention span-starved streaming watchers. In a film this dependent on slow accumulation — on that sickening build where every moment adds weight to what’s coming — the tease undercuts the dread it otherwise so meticulously develops. It’s an audience-insulting mistake of an opener. (I don’t know if the Sundance theatrical screening included this bit, or if it was an addition to the Netflix cut.)

Still, The Perfect Neighbor is one of the most arresting and unsettling documentaries in recent memory precisely because it doesn’t sand down its own contradictions. I’m marking it down a tick because I just feel a bit ooky about the whole affair, and I can’t help but feel some sort of ethical quandary about always-on cameras is opened with such a work, which I feel quite unresolved about. But it’s unquestionably devastating to witness the human impact of a murder, whose build-up and fallout barely masks systemic American issues, in near-real time. The film effectively boils blood in recognizing how quickly a scuffle with a neighbor can become a dead Black woman when racism, paranoia, guns, and legal permission structures all line up like fucked-up dominos. (Notably, and surprisingly, the police are mostly unimplicated in the footage we see, except by association with America’s broken institutions.) It’s also effective in how it points you toward the obvious takeaways without preaching them. It doesn’t need to. You’re already sitting there, watching a broken nation give them to you through a fisheye doorbell lens.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.