Dad-sad Brad astra

Ad Astra is one of the most beautifully shot and produced science fiction films of the 21st century. It is full of bold images of space travel, and buoyed by remarkable, evocative sound design. There’s a version of this movie, somewhere in the multiverse, that is a masterpiece. In our timeline, though, it’s barely good. The culprit: James Gray’s relentlessly diagrammatic screenplay, painfully on-the-nose like a blackhead zit. It’s like he wrote a first draft, then annotated every emotional beat in red pen and filmed the notes instead.

Gray, it seems, is a bit like cilantro: either he gives deliciously earnest flavor, or he tastes like soap. I’m in the “soap” camp, it seems. This is the second film of his I’ve seen, the first being Armageddon Time, another movie that wanted badly to be soulful and heartfelt but ended up a clumsy seminar in “big ideas we should all learn” (wow, racism is bad). Gray doesn’t write stories, it seems; he dictates concepts into story shape.

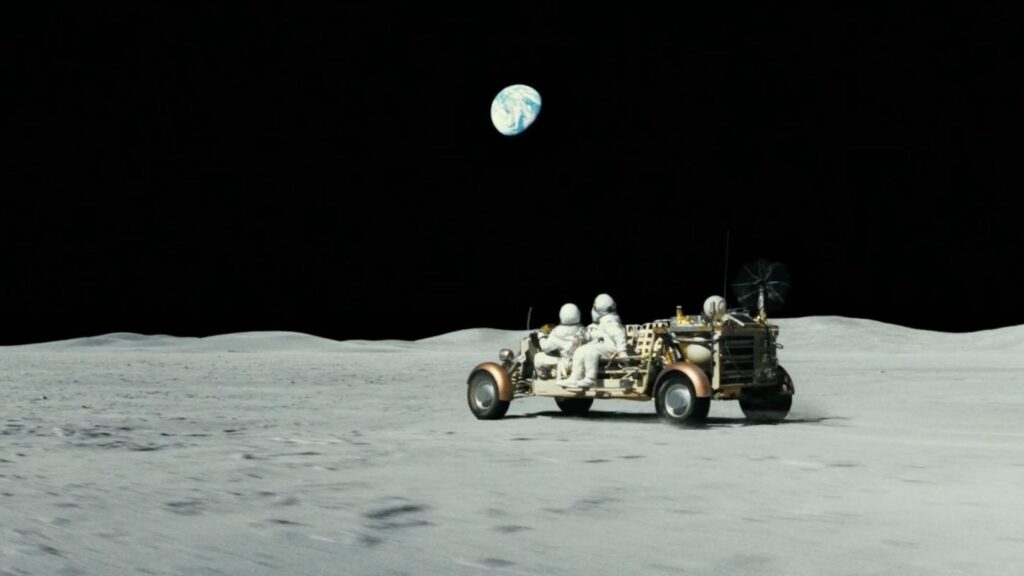

Set in a near future where humanity has developed the infrastructure to commute casually to the Moon and Mars, the film follows Major Roy McBride (Brad Pitt), a famously unflappable astronaut tapped for a mission that’s half interplanetary diplomacy, half therapy session. After a series of devastating power surges rattle Earth, Roy learns they may come from the Lima Project, a long-lost expedition to Neptune captained by his presumed-dead father Clifford (Tommy Lee Jones), a Buzz Aldrin-esque spacefaring pioneer. The solution is to send Roy on a cross-system journey to record a voicemail for his dad, asking him to pretty please stop unleashing gamma lasers on the homeworld. It’s a journey that takes Roy farther and farther from Earth, both literally and spiritually.

As Roy travels outward — first to the Moon, then Mars, then eventually beyond that — society thins out with him. Civilization becomes less ordered. Lunar malls give way to Martian bunkers, which give way to a sparse frontier. Roy’s journey is structurally an inverted version of Dante’s Inferno — concentric circles of sci-fi landscape, growing icier and more dangerous as you go further out rather than further in. Each planetary ring is another emotional crucible. By the time he reaches the destination of the climax, civilization is just a whisper in the void, and he’s almost literally talking to ghosts.

But just describing the plot doesn’t quite convey the experience of watching Ad Astra. The film’s most distinguishing feature might be its sound design: hushed, enclosed, chilly. We hear what Roy hears in his helmet: dampened voices, distant clangs, and the subtle thrum of space travel isolation. It’s beautifully executed and fully in sync with Roy’s inner world, his desperate attempts to connect with something or someone besides protocol, which is all his dad left him. The whole sound design has a narcotic calm to it. I actually had to watch in multiple sittings because I kept dozing off, and I mean that as a compliment. Few films have such a meditative, almost ASMR texture.

And then there’s the voiceover. Oh Lord, the voiceover. It’s not just a narrative crutch, it’s a full-on narrative exoskeleton. Roy narrates everything: his feelings, his non-feelings, his dad, his not-dad, his job, his thoughts about his job, his childhood trauma, his hopes, his absence of hope. I’m no voiceover prude — I think The Wonder Years is one of the great American texts — but this is the bad kind of narration. It’s ponderous and flabby, crowding out the images and flattening the mood. Pitt delivers it in a stern, introspective cadence that enhanced my sleepiness.

What images, though. If Gray’s pen is clumsy, his camera is astounding. With cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, doing his best “what if Roger Deakins shot an Apollo mission?” imitation, Ad Astra conjures some of the most striking sci-fi compositions and lighting since, well, Deakins’ Blade Runner 2049. We get planetary vistas rendered in striking color palettes, ships riding the precipice between darkness and sunlight, zero-G corridors that twist into near-abstraction. Even when the script dodders along, the visuals stay steady, immersive, and often extraordinary. Production designer Kevin Thompson and costume designer Albert Wolsky also deserve shout-outs for crafting a universe that feels not just near-future functional, but a bit haunted: practical tech as a counterpoint to a story operating in the mode of dreams.

At the center of all this is Brad Pitt, who has the unenviable task of carrying the movie both in screen presence and psychological depth. He does it well, but not well enough to fully convince me he’s the right man for the job. Pitt brings a composed, aging gravitas to Roy that reads as stoic, even noble, but the role seems built for someone less composed, more nervy, and younger. (I thought of Miles Teller.) Still, Pitt makes the most of it in quiet flashes, like when his eyes gently twitch as he undergoes a verbal psychological exam. My reservations on his casting aside, it’s a great performance that captures interior oceans of ache, mostly via small gestures and line readings.

Ad Astra is a movie I suspect inspires unusually subjective and divisive movie-watching experiences, depending on how allergic each viewer is to James Gray’s storytelling choices and how much they’re willing to suffer through tedious explication. The narrative is simultaneously overcooked and obtuse: characters announce emotional turning points with cue-card directness, even as major ideas — like the briefly suggested existence of aliens (that we can infer might be God), or how, exactly, a small station near Neptune managed to launch bursts energy flares across the solar system (antimatter or something?) — drift away unresolved or shrugged off. Sometimes the movie is both over-engineered and under-developed at once, like in the bizarre CGI baboon attack sequence, in which Roy encounters a murderous space monkey (which he declares, in voiceover, reminds him of his dad) that he never mentions or thinks about again.

For me, Ad Astra lands just on the right side of the recommendation line. The craft is just that terrific, the audiovisual texture just that rich and immersive. This film has jaw-dropping moments of scope, and even a handful of tear-jerking sequences in which the emotion successfully seeps through the spongy writing. But my recommendation comes with an asteroid-sized asterisk: Ad Astra is a frustrating film. It never fully gets out of its own damn way. For as much as the presentation and scenario suggest a quiet film about isolation and cosmic emptiness, the actual movie is cluttered and constantly distracting. Ad Astra is ultimately a beautiful, hollow object — as distant and easily forgotten as an absent glance into a starry sky.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

3 replies on “Ad Astra (2019)”

Right on. That voiceover, man. It’s what I imagine Blade Runner’s theatrical cut to be like (down to a protagonist who’s more-or-less a Replicant), but I’d be deeply interested to see this again without it. Still have kind of been meaning to rewatch it anyway.

Oh man I’d watch the hell out of a no-voiceover edit of this film.

“Frustrating” is the word. It feels like all the talent required for a masterpiece was present, but it didn’t quite converge.