"Refined olive and rapeseed oil" doesn't have the same ring

The terms “sad Oscar-bait drama” and “George Miller banger” seem incompatible on the surface; a contradiction in terms. And yet that is what we have with Lorenzo’s Oil, the fifth feature film by Miller. In the spirit of The Elephant Man or (to a lesser extent) The Social Network, Lorenzo’s Oil shows us a distinctive genre director’s take on conventional Hollywood middlebrow material.

It’s a grueling film: 135 minutes long and putting its character through the gauntlet. And yet there’s a spark that prevents it from devolving to misery. The opening half hour in particular is divinely great and strange before the film pivots to slightly more straightforward, though still engaging, storytelling mode.

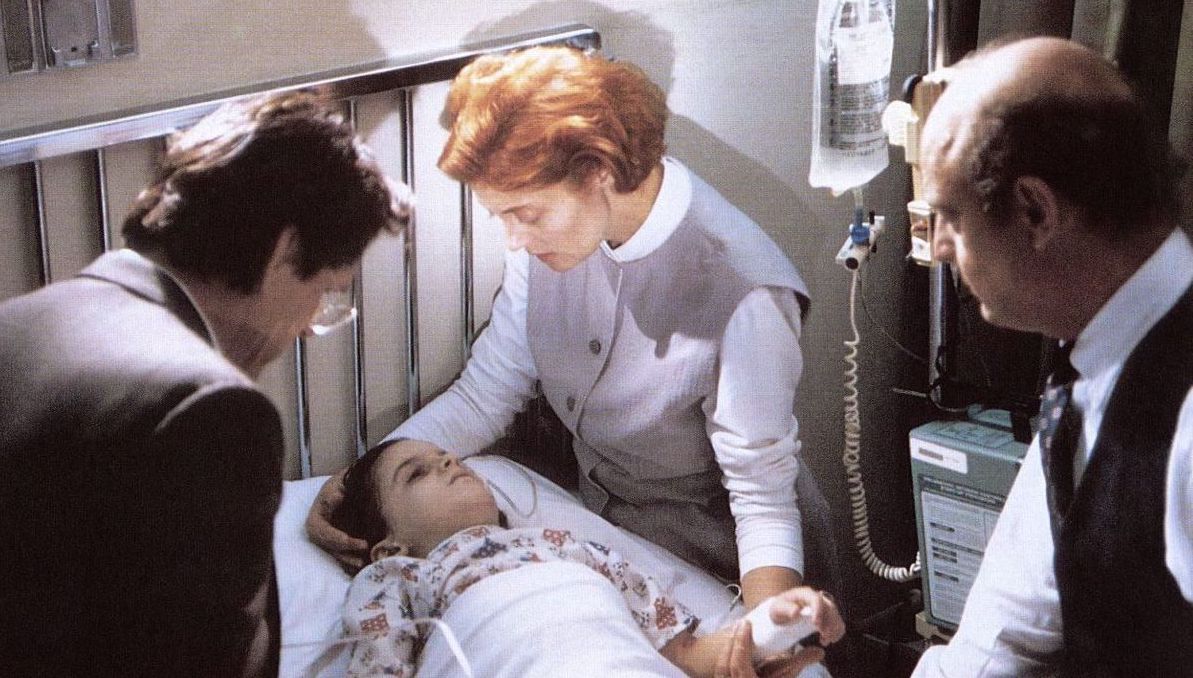

Lorenzo’s Oil follows the quest of Augusto (Nick Nolte) and Michaela (Susan Sarandon) Odone to find a cure for their son Lorenzo’s (Zack Greenberg) rare, brain-rotting disease. The couple reject medical consensus in their own intellectual and spiritual journey, doing their own research and experimentation to try and find the missing piece in the cure for Lorenzo’s condition. Meanwhile, they try to maintain hope and sanity as Lorenzo’s condition worsens to a horrifying, vegetative state.

Nolte and Sarandon are the film’s anchors, and both are terrific. Sarandon is more squarely in awards-bait territory as a devastated mom, commanding the screen with each new stroke of bad luck. It’s an excellent performance. She’s never shrill, genuinely moving. Nolte, by contrast, goes to an otherworldly place with a totally unconventional turn: He adopts a thick Italian accent and acts as if he’s a Michaelangelo sculpture come to life. He carries himself with hulking, operatic physicality, his face carved with tragedy. He repeatedly has old, fancy glasses dangling from the tip of his nose or off his face like crystal teardrops. It’s a wacky and brilliant role for the great Nolte.

Critic Mike D’Angelo is among several writers who have equated the film to “torture porn” in the physical degradation that Lorenzo goes through. Perhaps. But I find Miller’s take on the ailing child to be surprising and almost… I feel gross saying it… thrilling: He frames Lorenzo as a Gothic horror creature, wailing and flailing, a fresh wave of brutal monstrosity emerging with each scene. I would go so far as to say Miller is having some baroque fun with turning a disease-ridden child into a repellent object of terror.

Miller shoots the film almost entirely in close-up, giving every moment an arch emotionality. Especially profound are some over-the-top segments early in the film when the Odone family learn about the terminal diagnosis and come to grips with it: In one great montage, Nolte finds himself howling as his agonized figure is double exposed with terrifying words likes “quadriplegic” from a medical journal. Another brilliant sequence occurs during a church service: A remarkable top-down shot shows Sarandon pleading directly to the heavens for mercy.

The film’s second half has a much more typical cadence to it, and the result is a film that overstays its welcome a bit. There’s an especially odd rhythm to the very end of the film, as the story concludes on a memorable, bittersweet-but-happy note… only for the film to more-or-less exactly replicate the scene, dampening the conclusive impact.

But I think the movie gains more than it loses from its familiar structure and beats. Miller is an instinctual, unconventional visionary at heart. In something freeform like The Witches of Eastwick, the result is a film that follows his every whim and ends up as a shapeless and indulgent overall product. The structure inherent in Lorenzo’s Oil’s narrative, even if it’s just a retelling of a true-life event as a mainstream drama, constantly points Miller in the right direction. He can never go too far afield in a story with such a clear arc. My first guess was that he had adapted somebody else’s screenplay, but that’s not right: Miller is one of the film’s writers, along with fellow Australian Nick Enright. I guess his overarching storytelling instincts are developing.

Post-COVID, some of Lorenzo’s Oil plays differently. It leaves an odd aftertaste some might found off-putting. In short, Augusto and Michaela’s activism against the advice and wisdom of scientists and doctors is extremely evocative of anti-vax conspiracy thinking. It fits well enough I could see the movie being used as propaganda by the anti-vax movement, honestly. Miller doesn’t help matters by playing up the heroic aspects of the story and downplaying the story’s mixed legacy; the truth is that the titular oil is no miracle cure in real life.

But it ultimately is not really a mark against the film in my eyes. The Odones’ battle against the establishment is not conspiratorial; it’s the quest of a plucky underdog. They admire and work with doctors, just wish they would act a little bit more urgently and with more compassion. Their discoveries are not hare-brained theories that outright reject modern medicine, but clever and reasearch-based in ways that are ultimately backed and prescribed by doctors. I’m sure many anti-vaxxers would describe their vaccine skepticism and alternative treatments in similar terms, of course. But the anti-big pharma theme is ultimately no more than a strange undercurrent to Lorenzo’s Oil.

It’s quite exciting to see George Miller’s prodigious creativity and directorial vision targeted towards a new kind of material. Through five feature films, it’s clear he has the touch and the vision to synthesize strange ideas and push boundaries. Across his early filmography, the success or failure of the final product is less about whether he has the mojo (he certainly does) but more about how successful he is in shaping it and channeling it into something cohesive. His stronger stories — this, Mad Max 2 — pop off the screen and hold together into stories with propulsion and shape. He’d continue his genre expansion into children’s fables with Babe, a film he would produce and influence but not direct, which was a choice he’d regret and spend a lot of energy trying to make up for in the following years.

- Review Series: George Miller

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.