This is a guest post from friend of the site and podcast, Andrew Milne, who hosts the Two Friends Watch podcast.

Hi there! A little context – a few months ago, Dan and Brian invited me to join them as a guest on The Goods: A Film Podcast, and because I’m forever seeking validation from others about the things I enjoy, I took it as an opportunity to gush about the Undisputed series of DTV martial-arts movies. You can listen to that discussion over here on Episode 120 of the podcast.

It was off the back of that discussion that Dan asked if I might put together an introduction to martial-arts cinema, similar to the introduction to slasher films solicited from our mutual friend Brennan Klein a while back. I accepted, and then I got kind of carried away with it.

I’ve been immersed in martial arts films for more than half my life at this point, and I find the various ways that melee combat can be aestheticized endlessly intriguing. This article is intended as a kind of roadmap for viewers who are new to the genre, to provide an overview of its history and the various styles and subgenres that have waxed and waned over the decades. If that’s you, then I hope you find it useful!

A few things to note before making recommendations:

- We first need to define some terms. “Martial-arts movie” and “kung-fu movie” are distinct phrases. “Kung-fu” is an umbrella term that refers to the tradition of Chinese martial arts, dating back thousands of years.

- “Martial-arts” stories and cinema have deep ties in China, going back to the silent era. Historically, most films in the genre are Chinese or Chinese-language. Other countries have their own martial-arts traditions independent of kung-fu, but the idea of a film whose raison d’etre is its fight choreography is, essentially, a Chinese export.

- We also need to differentiate between “kung-fu movie” and “wuxia.” The term “wuxia” translates to “martial heroes.” It’s a storytelling genre that originates in popular Chinese literature of the early twentieth century. These are usually set in pre-modern China, feature elements of fantasy and magic, and are narratives of young, male protagonists on an individual heroes’ journey.

- Kung-fu movies actually originate as a kind of backlash against wuxia films. Where wuxia movies tended to rely of special effects and fantasy elements for their spectacle, kung-fu films emphasise the prowess of the onscreen performers.

- Kung-fu cinema became popular in the 1970s, with films being produced in large quantities in Hong Kong (still a British colony at the time), and also started to be distributed en masse in the west. From the perspective of a western fan, the history of martial-arts movies effectively begins in the late 60’s, with the work of directors like King Hu and Chang Cheh.

- I don’t count Japanese chanbara (samurai movies) as martial arts films – those are their own thing.

- Also, please bear in mind: I’m not an expert on this topic (or, indeed, any topic). I maybe know a bit more about martial-arts cinema than the average guy in the street, but there are gaps in my knowledge, and I will try to flag these as best I can.

- Here is a Letterboxd list of all of the recommendations below

Recommendations (or, the martial-arts movie iceberg):

The Gateway Drugs

- Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) – The first film I’d recommend to any complete newbie looking to get into the genre. Not only is it a legitimately excellent film that tells a compelling story, it’s kind of tailor-made for that exact function. Ang Lee wanted to make a film palatable to western tastes, and it’s been smoothed of some of the genre idiosyncrasies that might alienate us (broad slapstick comedy; extreme violence; choppy pacing). But it does that while remaining authentic – the fight choreography by Yuen Woo-Ping is legit, and there’s a reason it rocked people’s world in the west when it came out.

- The Matrix (1999) – Also choreographed by Yuen Woo-Ping, also a remarkably successful incursion of Hong Kong sensibilities into the Hollywood zeitgeist.

- Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003) – Tarantino draws on a lot of tropes from old-fashioned genre movies, but Hong Kong martial arts films are a big part of that mix, particularly in the climactic fight scene with the Crazy 88, again choreographed by Yuen Woo-Ping and featuring Gordon Liu. (Also Kill Bill: Vol. 2 (2004), to a lesser extent.)

- Kung Fu Hustle (2004) – Stephen Chow’s daft, creative slapstick comedy. Extends a hand across the aisle from the tradition of martial arts cinema to anyone who likes Looney Tunes.

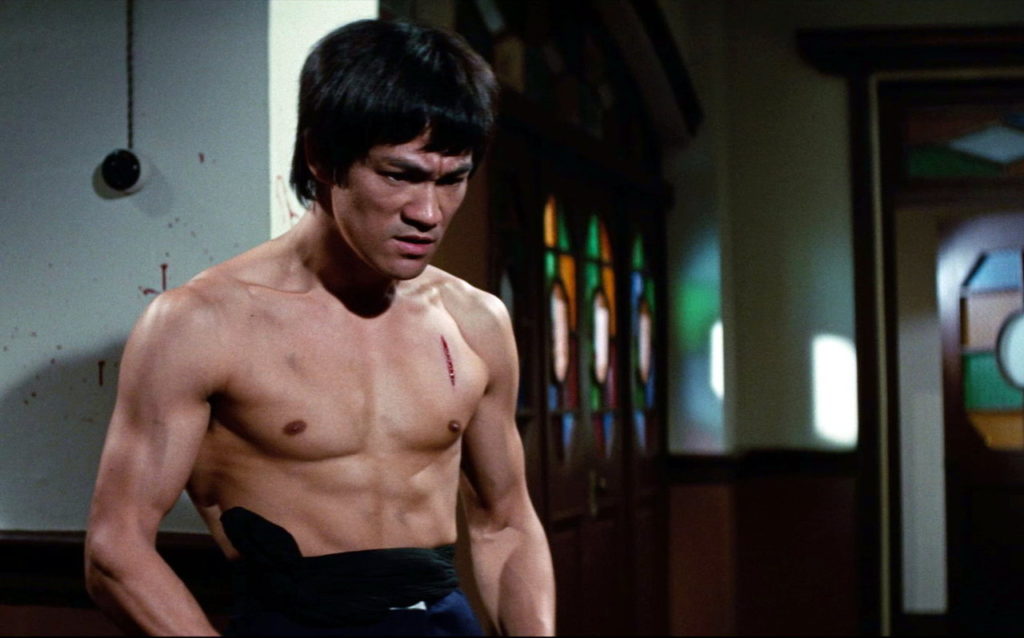

Bruce Lee

There’s probably no one individual more responsible for bringing the tropes of martial arts movies to the west, and he’s a colossally influential figure in the east as well. The four films he starred in before his premature death in 1973 look pretty dated now, but they’re a critical part of the genre’s DNA. Other major figures in the genre like Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung got their start as stuntmen in Bruce Lee pictures. His moves, his look, and the mythology surrounding his life have been endlessly referenced, remixed and parodied.

- The Big Boss (1971) – Pretty crude early effort when he was still working out his star persona. A bleak revenge thriller – it’s not great, but it’s an interesting curio.

- Fist of Fury (1972, aka The Chinese Connection) – IMHO his best film – the dojo fight early on codified what a “one-man versus a roomful of opponents” fight scene would look like for decades after.

- Way of the Dragon (1972) – A lighter, more comedic film, best remembered for the epic one-on-one fight with Chuck Norris at the climax.

- Enter the Dragon (1973) – the first true co-production between Hollywood and Hong Kong, the film that made a million suburban American kids sign up for karate classes. I personally – whisper it – think it’s kind of overrated, but its influence is irrefutable.

The 60’s and 70’s (The Two-Guys-in-a-Meadow Era)

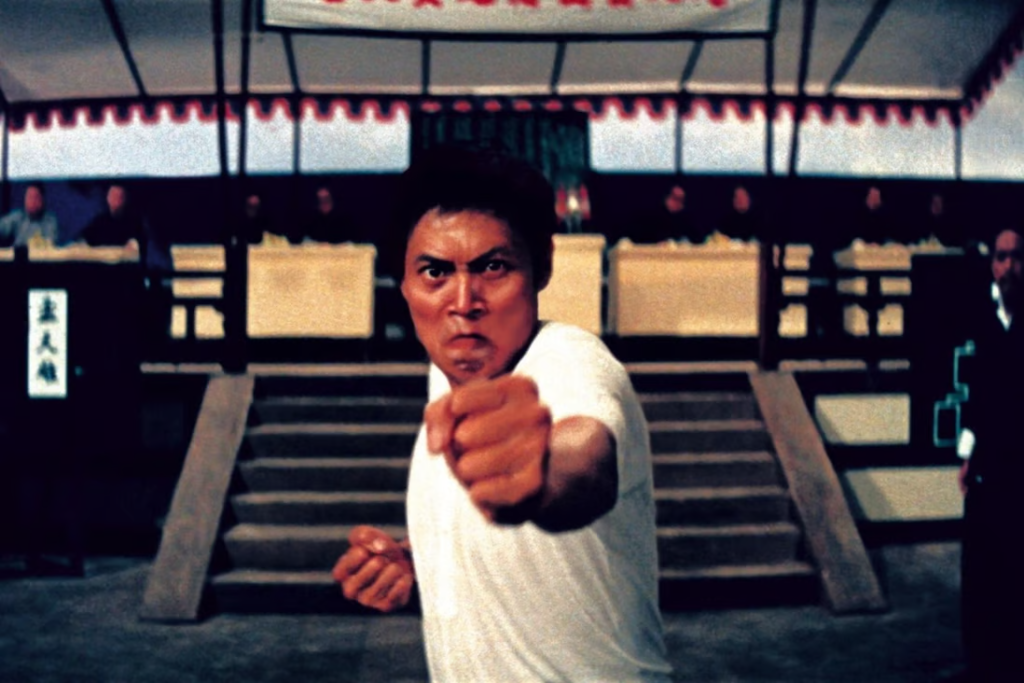

The first wave of kung-fu films has a distinct flavor to it. The most prominent production house of martial arts movies in Hong Kong was Shaw Brothers Studios, founded by Runme and Run Run Shaw, who came from a family who owned a theater in the early 20th century. Maybe that’s why films from this time tend to look very “stagy.” The camera tends to be quite static, favoring proscenium shot setups. The movies are generally period pieces, but they feature fake-looking, brightly colored props and costumes; the sets are conspicuous; the violence uses a lot of old-fashioned, Hammer-Horror-style bright-red stage blood.

The fight choreography, similarly, always looks very “rehearsed,” fighters going through elaborate combinations of moves that have clearly been worked out well in advance. The archetypal fight scene from this era involves two guys walking up to each other in an empty meadow in the middle of the day, and enacting a long, wordless dance sequence together punctuated by metronomic foley effects that only sort of looks like a fight. Watching this style nowadays is an acquired taste, but it’s a very particular kind of pageantry with an inimitable charm to it.

(I confess, I’ve not seen as many early kung-fu productions as I’d like. I’m working to remedy that – for now, mea culpa, this list isn’t as representative as I’d prefer)

- The One-Armed Swordsman (1967) – An early hit from director Chang Cheh; a dark, torrid melodrama that established Jimmy Wang Yu as arguably the first international martial-arts star. More a wuxia than a kung-fu picture, strictly speaking, but a great example of the Shaw Bros. house style, and still tremendously entertaining. Followed by several sequels and spin-offs.

- Five Fingers of Death (1972, aka King Boxer) – Known as the first kung-fu film to become a breakout hit overseas, reaching #1 at the U.S. box office in 1973 (curiously, director Jeong Chang-hwa was South Korean, and star Lo Lieh was originally from Indonesia). It’s a big, silly, violent soap-opera about warring martial arts schools; hellaciously fun, and a major early influence on Quentin Tarantino.

- Hand of Death (1976) – An early film by legendary director John Woo, featuring early appearances from Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung. It’s pretty meat-and-potatoes, but it gets to the good stuff fast and the fights are uncommonly ferocious for the time.

- Five Deadly Venoms (1978, aka The Five Venoms) – A curious instance of a Shaw-style kung-fu picture combined with a detective story, a great example of the house style and of director Chang Cheh.

- The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978) – The movie that made a name for great kung-fu director Lau Kar-Leung. It’s an interesting case of a kung-fu movie that emphasizes the process of the main character’s training more than the life-or-death conflict. Actually really, really good, and notable for having been a big influence on early hip-hop music, in particular the Wu-Tang Clan.

- Drunken Master (1978) – This put both star Jackie Chan and choreographer Yuen Woo-Ping on the map, with some truly incredible sequences that pushed the boundaries of kung-fu choreography’s potential for physical comedy rather than drama.

- Last Hurrah for Chivalry (1979) – Another early John Woo banger – a story that combines his favourite themes of honour and male bonding with some indulgently extended scenes of fantastical swordplay.

- Special mention – A Touch of Zen (1971) – King Hu’s wuxia masterpiece. It’s a true anomaly, a three-hour epic that combines a ghost story with political intrigue and Buddhist spirituality, set against some of the most drop-dead gorgeous photography of the Chinese countryside I’ve ever seen. The martial-arts element is light, but I felt I had to mention it, because it might be the most capital-G Great Film ever to be described as a martial-arts movie.

The 80’s (The Let’s-Test-What-Our-Insurance-Will-Permit Era)

Shaw Brothers Studios started to wind down with the arrival of the 80’s, and shuttered production altogether in 1986. Their rival studio, Golden Harvest, rose to fill the niche the Shaws had vacated, and with them came the ascendancy of stars like Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao, Sammo Hung, Michelle Yeoh, and Chow Yun-Fat.

The style of films they spearheaded in this era are as strikingly different from the films of the 70’s as American films of the same decade were from their predecessors. The trend shifted from period pieces towards modern day action thrillers focused on cops and gangsters. Cutting got faster; sets got more elaborate; the incorporation of props into fight scenes became de rigeur. Out with two guys in a meadow; in with a bunch of guys getting kicked off of mezzanine floors and through panes of sugar glass. Choreography became more spontaneous; less of a staged technical demonstration, more of a showcase for stunts that were freely incorporated into scenes of car chases and gunfights.

- Duel to the Death (1983) – A terrific swansong for the period wuxia, and a showcase for the talents of debut director and choreographer Ching Siu-Tung.

- Project A (1983) – The first time that Yuen Biao, Sammo Hung, and Jackie Chan (all alumni of the Peking Opera School) worked together onscreen. An amazing tribute to the era of Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd’s silent slapstick and a roller coaster of foolishly courageous stunts.

- The 8 Diagram Pole Fighter (1984) – The last really notable Shaw Brothers production, and Lau Kar-Leung goes so hard to make it a grand finale. I almost can’t overstate how awesome and bugfuck-nuts the last 20 minutes are.

- Police Story (1985) – The film that truly codified Jackie Chan’s identity as a performer and as a director, as well as the look and feel of Hong Kong movies generally for years to come. The final action scene is even more awesome and bugfuck-nuts than 8 Diagram Pole Fighter’s.

- Tiger on the Beat (1988) – On the one hand, this movie is viciously misogynist. On the other hand, Conan Lee and Gordon Liu fight with chainsaws in a scene that sends me into a bliss-trance.

- Tiger Cage II (1990) – Stars the up-and-coming Donnie Yen, directed by Yuen Woo-Ping, and it doesn’t let up for a single goddamn second. One of the all-time great kung-fu sugar rushes.

The 90’s (The I-Got-Strings-to-Hold-Me-Up Era)

In the early 80’s, there were stirrings of Jet Li, the young wushu-wunderkind who made everyone else look like they were moving in slow motion. He had his share of roles, but it wasn’t until the turn of the decade that he teamed up with producer/director Tsui Hark, and magic happened.

The Hong Kong film industry, which had been flagging towards the end of the 80s, had a shot in the arm from the release of Once Upon a Time in China. It made period martial-arts movies cool again, but now they looked very different from the 70’s. Canted angles; fast-cutting; undercranking; dry ice and coloured lighting and bold, high-contrast cinematography; and the screenfighters are all using wires to augment their physicality. Kung-fu movies look like music videos now.

- Once Upon a Time in China (1991) – The film that started us on this path, and it’s pretty goddamn good. Jet Li plays Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-Hung.

- Once Upon a Time in China II (1992) – Its sequel, released eight months later, is even better (and features Jet Li’s first bout with Donnie Yen).

- The Legend of Fong Sai Yuk (1993) – Jet Li plays a different Chinese folk hero for a change, and it’s still pretty goddamn good.

- Iron Monkey (1993) – Donnie Yen plays Wong Fei-Hung’s dad, and teams up with Yu Rongguang to fight corruption. It’s pretty goddamn good.

- Fist of Legend (1994) – Jet Li remakes Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury, which at this point is basically playing a Chinese folk hero. It’s pretty goddamn good.

- The Legend of the Drunken Master (1994) – Jackie Chan decides to get in on this racket. He plays a Chinese folk hero – the same Chinese folk hero he played in 1978, and incidentally, the same folk hero Jet Li inhabited in 1991. It’s the BEST MARTIAL-ARTS MOVIE EVER MADE.

- Special mention – The Bride with White Hair (1993) – One I hesitated to bring up. Much like A Touch of Zen, the actual martial arts element here feels tertiary, but I wanted to flag it because it’s just such a ravishingly beautiful movie. Leslie Cheung and Brigitte Lin headline as star-crossed lovers in a doomed, gothic romance – imagine if Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon had been directed by Edgar Allan Poe, and you’re on the right track.

1997 (A Caesura)

On July 1, 1997, the British colony of Hong Kong was reincorporated by Mainland China. A lot of Hong Kong’s most prominent talent picked up stakes and moved to the west before the transfer was complete. Stars like Jackie Chan and Chow Yun-Fat, directors like John Woo and Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark… all headed west, cashing in on the cultural capital their successes in Hong Kong had bought them, and the Chinese film industry was left to transmute into something new. Martial-arts movies as a genre experienced a kind of diaspora, like dandelion seeds landing where they may, all over the world. In the 21st century, the genre becomes a much more disparate phenomenon.

Western Curiosities

I haven’t spoken much this primer so far about the kind of martial arts films being made in America throughout the 80’s and 90’s. Reason being, I set out to recommend movies that are good, and honestly, I think most western-made films looking to capitalize on the Orientalism craze of the 80’s were pretty bad; a pale imitation of what Hong Kong was doing in the same period. Stars like Chuck Norris, Jean-Claude Van-Damme, Steven Seagal, and Cynthia Rothrock were, and are, physically talented performers, but the material they were given persistently failed to show the extent of what they were capable of. You’ll find some fans who go to bat for movies like The Octagon or Bloodsport or Marked for Death, but not me, I’m afraid.

That said, there have been a few diamonds in the rough:

- Drive (1997) – Probably my favorite western-made martial-arts movie. Directed by Steve Wang and choreographed by Koichi Sakamoto, it stars Mark Dacascos and Kadeem Hardison in a road-trip buddy-comedy with sci-fi overtones. The leads have genuinely great chemistry, it’s funny and offbeat, and Dacascos is an absolute dynamo, tearing through action scenes to equal the upper tier of 80’s Hong Kong.

- Kiss of the Dragon (2001) – Of the leading roles Jet Li had when he came west, this one is the most straightforward, and the most satisfying, a meat-and-potatoes crime thriller with a ton of thrilling set-pieces. Choreographed by Corey Yuen, the director of The Legend of Fong Sai-Yuk

- The Transporter (2002) – the movie that made Jason Statham the god of schlocky, B-movie action in the first decade of the 21st century. The sequels had diminishing returns, but the action in the original is legit (also choreographed by Corey Yuen, as it happens). – (Read Dan’s review of The Transporter and Transporter 2)

- Ninja (2009) – We’ve spoken about the Undisputed movies – if you want more of that particular style of cheese, I’d recommend Isaac Florentine and Scott Adkins’ other franchise, a pastiche of the cheap 80’s American Ninja films that happens to feature some great choreography.

- Ninja: Shadow of a Tear (2013) – See above.

- Blood and Bone (2009) – Michael Jai White’s premier B-movie star vehicle. I don’t think it’s great, but it has a few terrific sequences. The final fight with Matt Mullins is legitimately fantastic, and it’s keyed in to the contemporary phenomenon of street-fighting promotions, featuring celebrity MMA stars like Bob Sapp and Kimbo Slice.

- Triple Threat (2019) – this film boasts a huge ensemble cast of contemporary action icons – Tiger Chen, Iko Uwais, Tony Jaa, Michael Jai White, Scott Adkins, and Michael Bisping come together for a great, big, martial-arts mosh-pit for 90 minutes. The story’s formulaic and it’s not the most ambitious movie in scope, but it delivers on the promise it makes to fans.

- Special mention – The John Wick franchise (2014 – 2023) – it feels sort of outside the scope of this project, for reasons I can’t quite articulate. I get the impression that these are movies seeking to be holistic action films, not “just” martial-arts movies. That said, director Chad Stahelski is a stuntman himself, and they are very much films made by action nerds, for action nerds. Chapters 3 and 4, in particular, bring in a lot of martial-arts talent. Mark Dacascos; Yayan Ruhian; Cecep Arif Rahman; Scott Adkins; Marko Zaror; and, of course, Donnie Yen.

Zhang Yimou and The Wuxia Wave

In the time since Hong Kong came back under Chinese sovereignty, we’ve witnessed the phenomenon of “blockbusterisation” – the process whereby Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong talent has been drawn into the film industry of Mandarin-speaking Mainland China. Recently, this has manifested in movies like Dante Lam’s Operation Mekong and Operation Red Sea, or Wu Jing’s Wolf Warrior movies. Massive action epics with big budgets, a military-tech fetish, and the express support of the CCP.

Before those films, in the wake of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, we got a run of expensive wuxia epics, spearheaded by arthouse-director-turned-populist, Zhang Yimou.

- Hero (2002) – Honestly, my favourite wuxia film. A gripping story of an assassin (Jet Li) recounting the steps he took to get within stabbing distance of the Emperor of China in the 3rd century

C.E.B.C.E. Some commenters have called it state-sponsored propaganda in favor of Chinese imperialism. I dunno… maybe? I mostly notice how beautiful are its colors, how thrilling and creative are its fight scenes, and how intriguing and twisty is its narrative. - House of Flying Daggers (2005) – A beautiful, melancholy, doomed love story, that’s graceful right up until it’s brutal.

- Shadow (2018) – Yimou re-emerges after a low ebb in his career, and directs an astonishing aesthetic spectacle in a monochromatic palette. The drama is downright Shakespearean; it begins with court intrigue, ends with bloodshed, and both are made to look baroque and otherworldly.

Thailand Steps Up! (A New Competitor Arrives)

In 2003, “Ong-Bak” was released, directed by Prachya Pinkaew and starring Tatchakorn Yeerum (better known to his English-speaking fans as “Tony Jaa”). This represented a concerted attempt by production company Sahamongkol Film to break into the space that Hong Kong had previously monopolized; movies with death-defying stunts and no digital trickery, exhibiting the local martial discipline of Muay Thai (Thai boxing). Producer, director and actor Panna Rittikrai had been making zero-budget knock-offs of Hong-Kong movies since the 80’s; now they had a chance to shine on the global stage.

It worked… for a little while. Tony Jaa became a breakout star, and all action fans had their eyes fixed on Thailand. But there were a series of botched productions, plagued by on-set drama and delays, and by the turn of the decade, box-office returns shrank exponentially. The screen talent was there, but the business acumen which had sustained the Shaw Bros. and Golden Harvest just wasn’t present in Sahamongkol Film. Panna Rittikrai died prematurely in 2014; the same year, Tony Jaa’s contract disputes with Sahamongkol Film left him effectively blacklisted from ever working in his home country again.

For a while, the Thai action film industry was a vanguard; now, ten years later, it’s a graveyard. But it left us some pretty cool stuff before it went:

- Ong-Bak: Muay Thai Warrior (2003) – Tony Jaa’s coming out party; the then 26-year-old star rips his way through a formulaic but solid plot about a young man from a remote village, retrieving the treasure stolen from his people. Still an absolute riot; the action design stresses “no wires, no stunt-doubles, no CGI,” and you can tell the difference. It feels like a corrective to the ethereal, weightless action of Crouching Tiger, every blow hitting like a freight train. A genuinely awesome film; still my favorite of the whole Thai wave. (Read Dan’s review of Ong-Bak.)

- Born to Fight (2004) – A star vehicle for Dan Chupong, a tremendously talented stuntman whose career never took off internationally the way Jaa’s did. And that’s a shame, because Born to Fight rips.

- Tom-Yum-Goong (2005, aka The Protector, aka Warrior King) – The spiritual successor to Ong-Bak, now that Sahamongkol Film realised they had the world’s attention. Again starring Tony Jaa, again directed by Prachya Pinkaew, the story is an incoherent, incomprehensible clusterfuck even by the standards of martial-arts movies, but by God, the virtuoso action compensates for it.

- Chocolate (2008) – A conscious attempt by the producers to create a “girl-version” of Tony Jaa. Jeeja Yanin’s debut is sort of problematic in its treatment of mental health, but once it gets going, she’s astonishing to watch.

- BKO: Bangkok Knockout (2010) – Low-budget thriller starring an ensemble cast of relatively unknown young screenfighters. The story about a class of Muay Thai students who are kidnapped and made to participate in a death game for the amusement of the idle rich is very silly and badly acted, but the pace is so relentless and the action design so creative that it’s hard to care. The best and the worst of the Panna Rittikrai approach to making movies.

Latter-Day Hong Kong (The Donnie Yen Era)

The Hong Kong film industry was left in a bit of a rough state after 1997. After the exodus of a lot of its most high-profile talent, the scene floundered for a while, casting about for an identity in the new political and cultural context. High-concept boondoggles like The Medallion, The Accidental Spy, and The Twins Effect give a good idea of how shaky the HK scene was around this period.

In the mid-2000s, it started to get a bit of its groove back, and that’s largely down to the emergence of Donnie Yen as one of the most hard-working leading men in world cinema. Through his 40s and 50s, to this day, he’s continued to push the boundaries of fight choreography, showcasing a variety of styles and incorporating elements of grappling and MMA, where kung-fu cinema has historically been very focused on striking.

This era has had its share of wuxia and period pieces, but I’m most interested in the line of hard-boiled, neo-noir crime movies that feel like direct descendants of the kind of movies Chow Yun-Fat and John Woo were making in the 80’s.

- Sha Po Lang (2005, aka SPL, aka Kill Zone) – The film that kicked Donnie Yen’s run into gear. The story is a by-the-numbers melodrama about morally compromised cops, but the fight design is legitimately revolutionary, incorporating techniques from judo and Brazillian jiu-jitsu into a kung-fu movie in revelatory ways.

- Flash Point (2007) – Same star and director as SPL; same general vibe. A pretty indifferent police procedural that ends with 20 minutes of God-tier action design – Yen’s final fight with Colin Chou is a kind of screenfighting miracle.

- Ip Man (2008) – Again starring Donnie Yen, again directed by Wilson Yip, but this is actually a biopic of the man who was Bruce Lee’s IRL instructor. This film was a massive, international hit; it spawned a raft of sequels and spin-offs and a whole fad treating Ip Man as a folk hero, much like Once Upon a Time in China did for Wong Fei-Hung in the 90’s. I actually don’t love this movie; I think it’s pretty formulaic and blandly middlebrow, similar to western Oscar-bait (its plot beats specifically remind me a lot of Cinderella Man). But its influence is too far-reaching not to mention, and Sammo Hung’s choreography is legitimately top-notch.

- Special ID (2013) – Another modern-day crime thriller, and in this one Donnie pushes the ethos of grappling and submission techniques to the limit; this movie has some of the most exhaustively technical manipulation of joints and of the weight distribution of fighter’s bodies I’ve ever seen choreographed. Your mileage may vary on whether it’s cinematic or compelling to watch but I admire how boldly it went for it.

- Sha Po Lang 2: A Time for Consequences (2015, aka Kill Zone 2) – A successor to the 2005 film, but this time directed by Cheang Pou-Soi, and starring Wu Jing and Tony Jaa in a plot to do with international organ trafficking. The action design isn’t a revelation the way it was in the original, but it’s a top-to-bottom better movie; the plot is a compellingly overheated turbo-noir, and the cinematography and camerawork showcase the stunts in dizzying, creative ways.

- Raging Fire (2021) – The final film by director Benny Chan, one of the great, stalwart Hong Kong guns-for-hire. Donnie Yen, 57 by this point, plays another unstoppable supercop, and still manages to look awesome doing it – like no-one else in the world could.

The Raids and the Raid-likes

In 2008, Gareth Evans, a screenwriting graduate and struggling independent filmmaker from Wales, traveled to Indonesia at the behest of his Japanese-Indonesian wife, who had contacts in the film industry in Jakarta. While he was there, filming a documentary on the local martial art of Pencak Silat, Evans met Iko Uwais, a hobbyist silat practitioner, then working as a driver for a telecom company.

Evans got the idea in his head to make Uwais a movie star off the back of his skill in silat. The results have left an indelible impression on the genre ever since; a new school of martial-arts filmmaking, defined by scenarios with a ruthlessly limited scope; the particular rhythms of Pencak Silat as a style; the lithe, sinuous, roving camera movements of DP Matt Flannery; and an emphasis on extreme, brutal violence.

The Raid was a huge international success, inspiring a wave of imitators not only in Indonesia, but throughout southeast Asia, and had its ideas co-opted by Hollywood. Gareth Evans has since moved back home to Wales, but the ripples he left in his wake have continued to propagate.

- Merantau (2009) – Evans and Uwais’s first collaboration. A story about a country yokel who’s good at silat travelling to the big city, getting caught up in the underworld, and silating his way out of trouble. It’s fairly formulaic, but shot and edited and choreographed with a muscular intensity that made it clear this crew were something special.

- The Raid (2011) – The promise of Merantau comes to fruition here. Iko, again playing a nice-guy Silat expert, is trapped in a murderous, expressionist nightmare and has to fight his way out. The intensity is off the charts; one of the few true action masterpieces of the 21st century.

- The Raid 2 (2014) – Evans and Uwais parlay the success of The Raid to get to make the film they wanted to make in the first place: a big, sprawling, tragic gangster drama. It’s a very different film from the first; loose and digressive, rather than tight and focused. But when it gets to the action, there’s literally nothing else on its level.

- The Night Comes for Us (2018) – Directed by Timo Tjahjanto, Gareth Evans’ friend and occasional collaborator, best known as a director of pornographically violent horror movies. Tjahjanto set out to make his own answer to The Raid, with judo champion Joe Taslim as the hero, and Iko Uwais as the villain. The result is THE MOST VIOLENT ACTION MOVIE EVER MADE. (This is not hyperbole. Exercise caution.)

- BuyBust (2018) – A Filipino film that draws upon The Raid’s “cops caught between a rock and a hard place” structure to critique the anti-drug policies of then-president Rodrigo Duterte. Massively ambitious, gorgeously shot, and with balls-to-the-wall action; I just wish its sound design and editing didn’t utterly let it down. A pretty good movie that should have been a masterpiece.

- Wira (2019) – A Malaysian film very clearly influenced by The Raid, up to and including the fact that its final fight is with Yayan Ruhian (The Raid’s main heavy). It goes so, so much harder than it needs to.

Find all these movies gathered onto a Letterboxd list here.

Andrew Milne is the host of Two Friends Watch. You can find him on Letterboxd.

Andrew is a 2012 graduate of the University of Dundee, with an MA in English and Politics. He spent a lot of time at Uni watching decadently nerdy movies with his pals, and decided that would be his identity moving forward. He awards an extra point on The Goods ranking scale to any film featuring robots or martial arts. He also dabbles in writing fiction, which is assuredly lousy with robots and martial arts.

2 replies on “Martial-Arts Movies: A Primer”

Wow, that is like a good dozen or more movies I need to watch! I should probably start with the Bruce Lee and Jackie Chans I own but haven’t gotten around to, though Bride With White Hair sounds especially tantalizing. “Cheung like Poe” sounds a lot like Rouge and I love Rouge. Also appreciate the recommendation of Last Hurrah For Chivalry, I’m a decent-sized Woo fan and have wanted to watch it but have not felt an urgent need to. I’ve been wanting to get more into Shaw Bros. stuff too.

Will point out that Hero’s 3rd century *BC.* I also think the extent to which its CCP propaganda is overstated (when Zhang claims the color is just an aesthetic he’s obviously lying to no small degre–red means the same thing everywhere–and the Qin’s historical color was black but that doesn’t explain why everybody looks like Palpatine), and that whole trilogy is just the most hopeless “I live in an autocracy that has no end” kinda thing. Then he apparently drank the kool-aid, because man, when he does CCP propaganda, it’s *really* not subtle.

Night Comes For Us is pretty great, I should watch that again, too.

D’oh! The SNAFU with the date on “Hero” is my mistake. I think I was getting mixed up with Red Cliff, which *does* take place in the 3rd century C.E.

*Definitely* check out Bride with White Hair – that’s a movie that I’ve evangelised for ever since I saw it a few years ago, it’s amazing.