One dead fingernail

Rushmore is Wes Anderson’s second film, but it really feels like his proper debut. It has a lot of Wes Anderson firsts, many of which would become hallmarks of his filmography:

- first film shot in anamorphic widescreen

- first official pairing with music supervisor Randall Poster (though Poster did assist with the Bottle Rocket soundtrack)

- first casting of Bill Murray and Jason Schwartzman

- first broken-down child-parent relationship

- first dissection of grief

- first play or movie within the movie

- first chapter titles appearing on screen

- first use of reality-breaking artifice (stage curtains in frame)

- first nested opening scenes

- first masterpiece

This is the moment where we learned what a “Wes Anderson movie” is. Everything he’s made since, nine features across 25 years, has been a refinement of or a reaction to Rushmore. Hell, the entire indie movie scene for ten years was indebted to Rushmore and Anderson’s writing and direction style. Reservoir Dogs opened the door to the Sundance indie revolution; Rushmore set a template for the ’00s, and a hundred Garden States and Junos came in its wake.

And there’s a reason this film kicked off a movement. It’s heartfelt and clever and damn great. Rushmore is a much more personal film than Bottle Rocket (and plenty of the movies he made afterwards, too): Anderson and Owen Wilson, who co-wrote the film, plumb their own adolescent awkwardness and growing pains to craft a one-of-a-kind teen comedy.

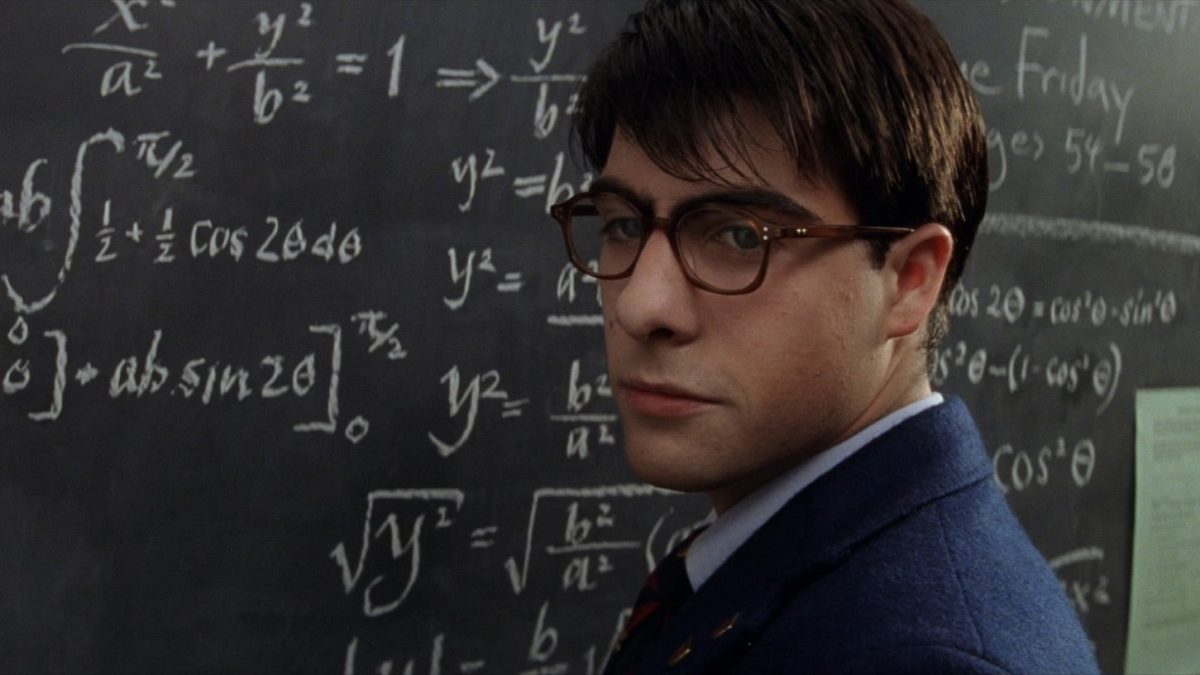

The story follows three characters all haunted by death and depression in different degrees: First, precocious 15-year-old Max Fischer (Schwartzman), whose mother died of cancer. Second, the lonely first-grade teacher Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams), whose husband drowned. Third, steel magnate Herman Blume (Murray), who survived Vietnam (”I was in the shit”) and now stuck in a loveless marriage with shithead kids. The trio criss-cross each others’ lives and butt heads during the fall and winter.

Rushmore is part of a long tradition of coming-of-age stories, but its own beast entirely. The film borrows tropes from boarding school stories, teen comedies, taboo student-teacher romances, love triangles, put-on-a-show revues — but yet is not quite like anything else, its own unique specimen.

Max is a student at Rushmore Academy. He is a jack-of-all-trades but a master of none, though he fancies himself a master of all. Everyone knows him, and most teachers and fellow students can’t decide whether or not they like him, though they lean towards “no.” He has the frustrating habit of trying relentlessly hard no matter how small or outlandish the task at hand, willing himself to whatever he wants. During the fall semester at Rushmore, he sets his sights on the affections of Ms. Cross.

His do-it-all busyness is a symptom of a bigger hurt: Max is haunted by the lingering specters: his mother’s unexpected death and his father’s willfully simple life. He rushes into an ambitious proto-adulthood to both make up for his mother’s lost time and defy his father’s simple ambitions. This informs the intensity with which he approaches everything, including his pathetic, awkward wooing of an adult woman. There’s a deep-seated irony in Max’s arc: It’s almost a reverse-coming-of-age. His growth is complete when he accepts he’s still a child.

There’s almost no preparation for how mature and inviting Anderson’s visual sense is here (unless, of course, you’ve seen any of his movies in the quarter century since). Rushmore is the moment Anderson bloomed as a generational stylist in film form and composition.

Rushmore is not quite as decadently embellished and painterly as his later films. But it’s still constructed in Anderson’s trademark geometric, symmetric, wide-frame arrangements. The film includes a blend of location shooting and soundstage shooting, and thus lacks the bespoke dollhouse cross-sectioning of sets we’d see as soon as The Royal Tenenbaums. The result is a sense of space and reality that is often missing (for better and worse) in his later films.

But if the set design doesn’t quite match his later films, his direction certainly does. The hints of a distinct style in Bottle Rocket are suddenly fully formed: the precision of the whip-pans; the slo-mo tracking shots; the full-frame ornamentation; and the outstanding fashion-magazine colors.

Anderson is also already offering self-awareness via nested stories and meta-commentary even at this early stage of his career: One of Max’s traits is that he creates stylized plays that use the stage in much the way that Anderson uses a film frame. Thus, a Max play is essentially a micro-Anderson film. Anderson would iterate on this recursive concept until it reached its logical endpoint in his recent French Dispatch and Asteroid City.

What really makes Rushmore special is not the style itself, but the storytelling of the film, which, of course, is brought to life by that terrific visual style. Anderson uses a narrative that has become his calling card: a bizarre juxtaposition of deep grief and angst for the characters’ internal lives, set against dry comedy as the exterior shell of the melancholy. The warm and the cynical, the pained and the playful, are in constant conversation. Anderson never flinches away from the off-putting Max, who borders on the sociopathic at times. And yet the writer-director reveals heaps of generosity upon his characters, including and especially Max. He emerges genuinely sympathetic, even heroic, by the film’s emotional finale. It’s a proper arc of character growth — for Max, but Herman and Ms. Cross, too — well-earned rather than tacked-on as it so often feels with Anderson’s imitators. It’s because Anderson and Wilson has written a rich, conflict-dense screenplay where nearly every line and joke pays off, with carefully ratcheted character development, all of which aligns perfectly with the film’s comedic flow and visual style as if by filmmaking magic.

The one real mark against Rushmore’s story is how much it plays with the squirm-inducing taboos of Max trying to woo his adult teacher. It’s honestly structured like a romantic comedy that would land the pair together, which is the only source of whiplash in the film’s tones. It’s some broken dramaturgy: The audience intellectually wants Max to overcome his hot-for-teacher crush, but the structure of the story pushes us towards wanting them to get together. Rushmore toes towards edgy in a way that doesn’t befit Anderson’s voice, a problem that would become even more glaring in The Royal Tenenbaums. But it’s ultimately not a backbreaker; everything else here works so well, and the ending is so satisfying, that the issue gets swept away in it all.

Rushmore’s ensemble is terrific and well-acted — another consistency across Anderson’s career (to the point of self-parody in Asteroid City). Schwartzman dodges nepo baby accusations (he’s a relative of Francis Ford Coppola) with a truly outstanding turn in his first-ever film performance, blending charm with smarm. He’s a perfect fit for Anderson’s stew of pathos and deadpan.

Schwartzman offers far from the only strong turn in the film: Murray gives one of the great performances of his career, both funny and deeply sad, a nice warm-up for The Life Aquatic, which is arguably his career apex. Williams fits the role of sad-eyed formality falling apart at the edges perfectly. The ensemble includes a million funny little performances that steal scenes for seconds at a time. Of special note is one particularly touching turn: Seymour Cassel as Max’s infinitely sweet and patient barber father.

Among Rushmore’s many terrific layers, one of its greatest is its pop soundtrack. The British Invasion music cues place the film in a nebulous mid/late-century setting: Rushmore is not a period piece (we can place it as contemporary based on Herman’s age and Vietnam experience), but has enough retro touches to feel like it could be. More importantly, the soundtrack provides tremendous emotional texture, each song adding rich dimensions to scenes and characters like a swelling wave. It culminates in one of my favorite needle drops and film endings ever: “Ooh La La” by Faces accompanies a happy-tears slow-mo group dance, evoking Wes Anderon’s beloved Charlie Brown Christmas. Honestly, Anderson and Poster’s careful, clever use of music for enriching the impact of each important scene is operating near Dazed and Confused levels. World-class music selection… and it’s, like, the fourth most notable development in Anderson’s craft.

Rushmore is one of the great films of the ‘90s and quite honestly one of my favorite movies ever. It’s a miraculous blend of tones and techniques that all still feel like a whole. And because it centers on a wounded teen whose many stumbles eventually lead to a discovery of truth and a strength of character, it is as uplifting as it is tempered with darkness and cynicism. Put another way, wayward adolescents are the perfect subject for Anderson’s style. As his stories become more adult and serious, his style sometimes ossify a bit. (Uncoincidentally, Rushmore and Moonrise Kingdom are my two favorites by the director.)

Perhaps most astoundingly of all, Rushmore is not a magical peak that Anderson would never touch again, but a mere launching point for a remarkable string of great films that places him among the very greatest directors of the past quarter century.

Is It Good?

Masterpiece: Tour De Good (8/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “Rushmore (1998)”

As Wes Anderson feels like he’s always had the soul of an old man, maybe that’s why my favorite is The Life Aquatic. Then again, Moonrise Kingdom is right there, duking it out with Grand Budapest and good ol’ Rushmore. It doesn’t help that this one still *feels* like a normal (even though it’s not really a normal), and not the infinitely fussy Anderson we’d be getting soon. (Not in The Royal Tenenbaums, necessarily–it’s actually less fussy than I remembered–and frankly I’ve probably just seen that one too many times because people who hate Anderson now still like that one, and for no good reason except I guess he got old for them, stylistically.)

I do agree that Anderson has “the soul of an old man” — the kind who reads the New Yorker and watches Godard films. So you’re right that makes it odd that my favorite Anderson films are centered on kids and teens.

My entire circle is pretty pro-Anderson, with maybe one exception, and even he frames it as “I am aware that his thing is not my thing.”

A lot of words spent on a boring movie.

Sorry this one didn’t jibe with you (the movie or the review), but thanks for stopping by!