I don’t even know where to begin. Imagine me staring speechless at a blank text box for several minutes as the prelude to this review.

Full context for the first (and, I assure you, only) time I watched this: I had recently caught up with A Trip to the Moon and The Great Train Robbery. Up next in my curated tour through film history via 1001 Movies to See Before You Die was The Birth of a Nation, which I’ve only ever known by reputation and stills. In fact, this was my first D.W. Griffith film.

From what I’d read I knew by reputation that The Birth of a Nation is a huge leap forward in cinematic technique; a remarkable piece of technical innovation and craftsmanship at a scale never before seen. Yet I was floored just how much of a leap it captures in barely a decade. I also knew the film as a racist film; and yet in practice I was flabbergasted just how vile and racist it actually is.

We must confront both poles, so I guess I’ll start with the technical achievement.

Most cinema before 1915 capped out at a reel or two in length (i.e. shorter than a half hour), with much less ambition than what we see here, frankly by an order of magnitude or more. We see this captured well in the two most-seen films of the 1900s decade by modern audiences, also the first two that appear on 1001 Movies to See Before You Die: A Trip to the Moon and The Great Train Robbery. Each is clearly a proto-film rather than a fully-formed example of the medium. They are primitive shorts that hadn’t yet figured out how to really make use of a camera or tell a robust story — little novelties, mostly. Charming novelties made with skill and passion, yet undeniably small. Even the basic building blocks of film — acting, editing, mise en scene, direction — were still works in progress. At heart, both feel like one-act plays captured on film with some cinematic ornamentation.

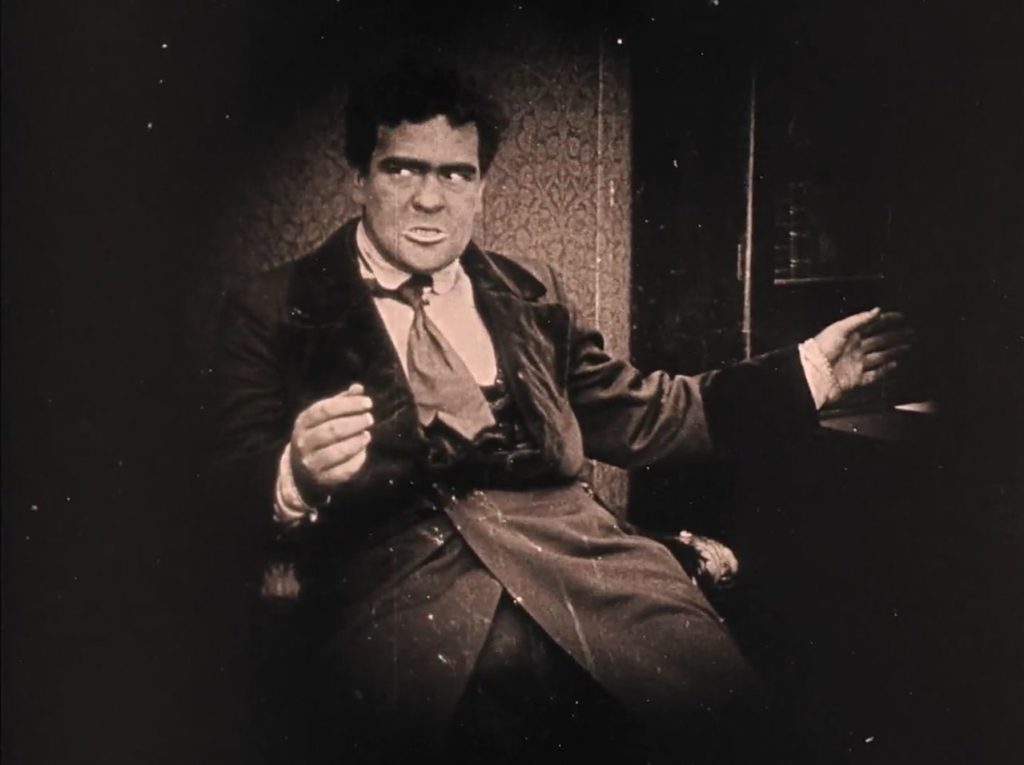

While I expected a leap in technique demonstrated in this formative work, I didn’t expect this much of one. The formal craft is vastly more mature: Griffith blends close-ups, long shots, and medium shots for clear cinematic and storytelling purpose. The film’s editing is remarkably sophisticated, and includes dramatic cross-cutting and smooth flow between shots and scenes. Shots are audaciously framed from different angles, throwing us in the middle of the action.

On top of all of that, Griffith has a clear instinct for the artistry and emotional potential of film as storytelling in a way only fleetingly captured in other early cinema. Close-ups of happy couples in each others’ arms are tender and moving; extreme long shots capture the awe of battle or the chaos of riots.

With the entire frame typically in focus (or irised into smaller circles or other shapes to draw our focus to snippets), Griffith captures vivid period detail in every frame. Sets and costumes are peerless reconstructions — though it’s good to remember that this movie was as far from the Civil War as today is from 1970. Much of the cast and crew involved had lived through the war (which I suspect Griffith and many involved would have labeled something like “The War of Northern Aggression”).

If nothing else, the sheer runtime and consistency of craft across that runtime is astounding. The twelve-reel film is typically screened at 3 hours today; compare that to A Trip to the Moon and The Great Train Robbery which both clock in close to 10 minutes.

For such a long movie, it’s rarely stodgy in its pacing: The variety of visual techniques and clip of the plot points made the reality of watching this movie not nearly as dire as I feared going into it.

But. Film is a narrative medium. Craft doesn’t happen in a vacuum. We can only discuss The Birth of a Nation as a complete product. We must confront the story that all of that overwhelming cinematic innovation is in service of. This is the “racist” part of the equation. And… Yikes.

The film is a 3 hour epic broken into two halves: 1) before and during the Civil War, 2) Reconstruction afterwards. The film follows a Northern and Southern family with strong connections as they navigate the War and its aftermath.

The first half is overflowing with casual racism. It’s in America’s muscle memory, of course — especially of a conservative white southerner like Griffith in the early 20th century — but it’s jarring to see so it on full display: Actors in tarry, ugly blackface (except the extras silently and obediently working the fields and doing housework, who are actually Black); The rhetoric of noble causes and states rights; The depiction of plantation owners as kind paternal figures; Black leaders as lecherous and corrupt.

It’s bad, but this racism is really only on the fringes of the story. In fact, this first half of The Birth of a Nation approaches watchable, especially the awe-inspiring battle scenes and the amazing reproductions of historical events like Lincoln’s assassination.

The second half is far more direct and sickening in its evil. It depicts the founding and rise of the KKK during Reconstruction in heroic terms. Its racism is the crux of the plot and so filthy that it literally made me queasy to watch. Every freedman is shown to be hunched, sloppy, sexually unhinged, drunken, stinky, and undignified. Black leaders are shown to unfit lechers, openly scheming about stealing away white girls and creating a “Black empire” to destroy whites.

So who should come in? The KKK, those “heroic” vigilantes. They “bravely” lynch a Black man (off screen) who was pursuing a romance with a white woman. That woman died after diving off a cliff rather than engage with a person of color.

The final climax is a cross-cut of two threads: 1) A horde of crazed Black people attempt to break into a cabin where white people are hiding. Sexual frenzy and aims of rape towards the white women inside are heavily suggested. 2) One of our white heroines is abducted by a Black politician who wants to make her his “Queen.” In both plot threads, the KKK rises to save the white people.

And then we get the denouement: The KKK intimidating Black people at the polls in the next election, preventing them from voting as citizens… again, depicted heroically! And the movie goes out on final double wedding of our white couples, God smiling down on them, “devilish” Black people fenced off, away from southern culture in a “victory.”

It all just left me speechless and horrified.

In addition to having a more vile and race-focused plot, the film’s second half is also a bit less breathtaking in its visual spectacle. But the craft is still remarkably inventive as a culmination of technique leading up to it, and this half includes plenty of breathtaking images: the sheer spectacle and chaos of the riots, the bone-rattling cross-cutting of the climax, the weirdly abstract and heavenly final white wedding, and a genuinely suspenseful sequence of a Black man stalking and chasing down a white woman.

What makes this movie so horrifying is that it contains both of those extremes. It is both so racist and so accomplished as a synthesis of early cinematic technique: If it was anything other than a masterpiece from a craft perspective, a groundbreaking achievement of filmmaking, then it would be a much easier stain on the medium’s history to wipe away and forget.

But it’s not, and that makes me hate it so much. That it is so effective at telling such an evil story makes it all the more the kick in the teeth as a watch.

In 2003, Roger Ebert wrote an essay on this film and how the modern world can come to grips with it. It has become one of the authoritative takes on the film:

“The Birth of a Nation” is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl’s “The Triumph of the Will,” it is a great film that argues for evil.

I love Ebert’s thoughtfulness and generosity of spirit, but I think he comes down way too kind on the film in his essay.

This is not simply an issue of a modern emotional reaction to a dated film or a bad story told well. The Birth of a Nation is an artifact of hate, something that created real and lasting damage in this world. It was a motivational tool for racists. The Klan used it for recruitment. It directly led to violence and hate in well-documented ways. Per History.com:

Until the movie’s debut, the Ku Klux Klan founded in 1865 by Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee, was a regional organization in the South that was all but obliterated due to government suppression. But The Birth of a Nation’s racially charged Jim Crow narrative, coupled with America’s heightened anti-immigrant climate, led the Klan to align itself with the movie’s success and use it as a recruiting tool… [KKK founder William Joseph] Simmons seized on the film’s popularity to bolster the Klan’s appeal.

In other words, The Birth of a Nation didn’t just depict the concept of hatred. It inspired it and weaponized it: As the KKK has done great evil, so this film is a key piece of that vile narrative.

For those reasons, I strongly recommend against watching this film unless you are deep into studies of film history. Search YouTube for the battle clips or the Lincoln assassination set piece, sure, but don’t dignify it with three hours of your life.

America was built on the back of exploiting people of color, so it’s only appropriate that its first masterpiece of filmmaking craft would do the same. But that doesn’t make it any less dispiriting.

PS: By strange chance, I finished watching this movie and writing the review hours before pro-Trump insurrectionists stormed the Capitol building on January 6, 2021. It was one of the most striking images in recent years of white supremacy and privilege driving the reins of conservative politics. As the cliche goes: The more things change, the more they stay the same.

- Review Series: D.W. Griffith

Is It Good?

Not Good (2/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.