As usual, the Americans got there after the Europeans, but did it with more scope and spectacle.

Edwin S. Porter was a Thomas Edison employee who started his career as a projectionist, using his experience assembling different shorts to bring new insight into narrative editing. As a director, he built upon the narrative filmmaking that Georges Melies was pioneering in France and applied some fresh new techniques to expand primitive film grammar. He achieved a lot of “firsts” (or, more accurately, “firsts that received wide distribution and press coverage”) — mostly in the realm of editing and camera movement. Less idiosyncratic and theatrical than Melies, who used ornate setting design and trick edits, Porter was a technical experimenter who dealt in real-life stories rather than fantasy. Like most early directors, Porter was a workhorse. The quantity of his directorial output is staggering by today’s standards: He’s credited with 250+ shorts. But unlike Melies and Alice Guy Blache, he never asserted a distinct voice as an auteur.

Porter’s most famous work, one that fits quite easily into a narrative of birthing American cinema and delivering terrific spectacle for the time, is The Great Train Robbery from 1903. It’s one of the first American narrative films, though any such distinction of “first” always has a million asterisks on it — so many people were fiddling in the field at the same time that achievement of the era was always incremental. Certainly, this was the biggest American-made hit of those precious “cinema of attraction” years when the sheer novelty of cinema was the main appeal.

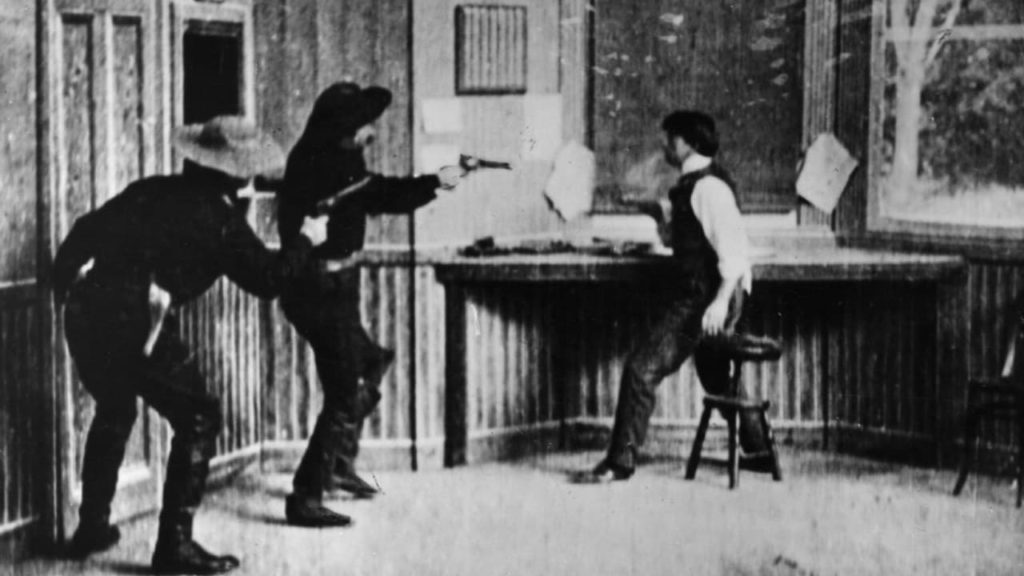

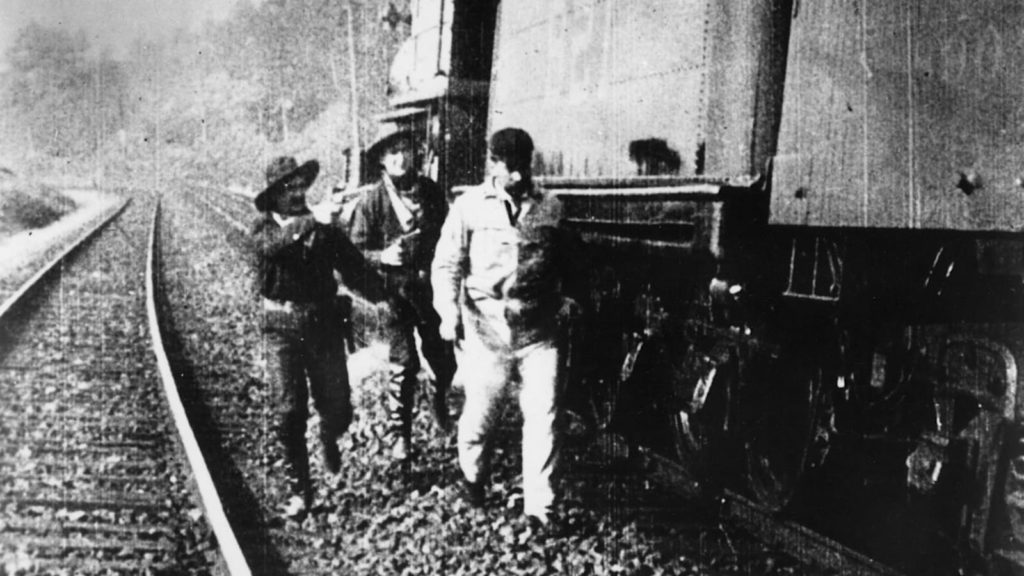

As you’d guess from the title, The Great Train Robbery is a very early western — perhaps a “proto-western” as we’d still want to call this a “proto-film.” Hell, you could call it a “proto-heist,” too. The story follows a group of bandits who plan and execute a train robbery only to be hunted down by a vigilante justice posse.

The Great Train Robbery’s biggest innovation is a brilliant early example “cross-cutting” editing, which would reach maturity in the ensuing decade before getting fully crystallizing The Birth of a Nation. This is a technique so basic and fundamental to our understanding of movies that it almost feels silly to talk about. Cross-cutting, also known as “parallel timelines,” is editing that cuts back and forth between two different scenes, tricking our brain into perceiving that they are happening at the same time though we only ever physically see one scene at a time. Prior to cross-cutting, in the actuality era, movies were limited to a single space and time, as if we were watching a stage show. But now, movies could capture an expanse of space and even time: one, a vigilante posse formulating; two, a pack of fleeing robbers; and — as if by magic — a third thing is created: an implicit tension and relationship between these scenarios, and an understanding that both are occurring at once.

The concept of editing as an expressive technique in-and-of-itself would take a couple of decades to fully formulate. And, again, the true innovation would take place in Europe, not America. (Although, American DW Griffith made some great strides before Sergei Eisenstein and other Soviet filmmakers would revolutionize editing in the 1920s.)

The Great Train Robbery has a few other key innovations. One moment that introduced a new kind of visual storytelling occurs during the criminals’ escape: As they flee pursuers, they appear to be cornered in the woods. But Porter pans the camera to reveal some horses unseen at the start of the shot. This careful revelation of the horses shows the camera as not just an innocent observer of the action but an active participant — its placement and movement become tools for communicating ideas by themselves.

In addition to this nuts-and-bolts technique innovation, The Great Train Robbery has some visual pop to it: The cut I saw has some hand-coloring and matting — i.e. an in-camera effect of implanting multiple shots on different parts the same frame through carefully covering certain parts of the camera lens, then running the film through the camera multiple times so they are composed together.

The movie’s real thrill is in its sheer spectacle and sense of danger: The majority is shot on location, not a studio. With live horses running towards the camera, rolling steam engines, and convincing gunfire, it’s not hard to imagine this as a sensational and visceral viewing experience at the turn of the century even though it’s quaint 120 years later. There’s even some raw emotion as passengers crowd a wounded peer after the bandits run off (though the acting is wildly inconsistent — some people are stiff as boards, others use over-the-top gestures as if they’re worried the folks in the cheap seats might not spot them).

The most memorable image of the film is the mildly revolutionary close-up: An actor dressed as a bandit firing a six-gun directly into the screen. The shot is not a part of the narrative: some cuts have this at the beginning of the film; others at the end. But it’s a truly striking image — right up there with Melies’s man in the moon and the train arriving at La Ciotat as the enduring images of nascent cinema. GoodFellas among others have visually quoted it.

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.