Great Scott

The doomed Terra Nova expedition for the South Pole in 1912 ranks behind only one other event, the sinking of the RMS Titanic, in the public imagination of early 20th century English tragedies.They have a lot in common: Both events are icy, fatal, and tinged with doomed drama — perfect fodder for mythmaking and symboliing the slow dissolution of English exceptionalism in the lead-up to World War I. Captain Robert Falcon Scott, a Royal Navy officer and one of the key figures of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, led a high-profile journey from the coast of Antarctica to the South Pole, determined to be the first man to reach that fateful dot on the bottom of the globe. Instead, the trip became a nightmare. The entire mission collapsed under the weight of weather, miscalculation, and the futility of man against nature. A century later, observers still debate why it happened, what it all means, and whether Scott died a brave martyr or a tragic fool. The answer is likely a bit of both.

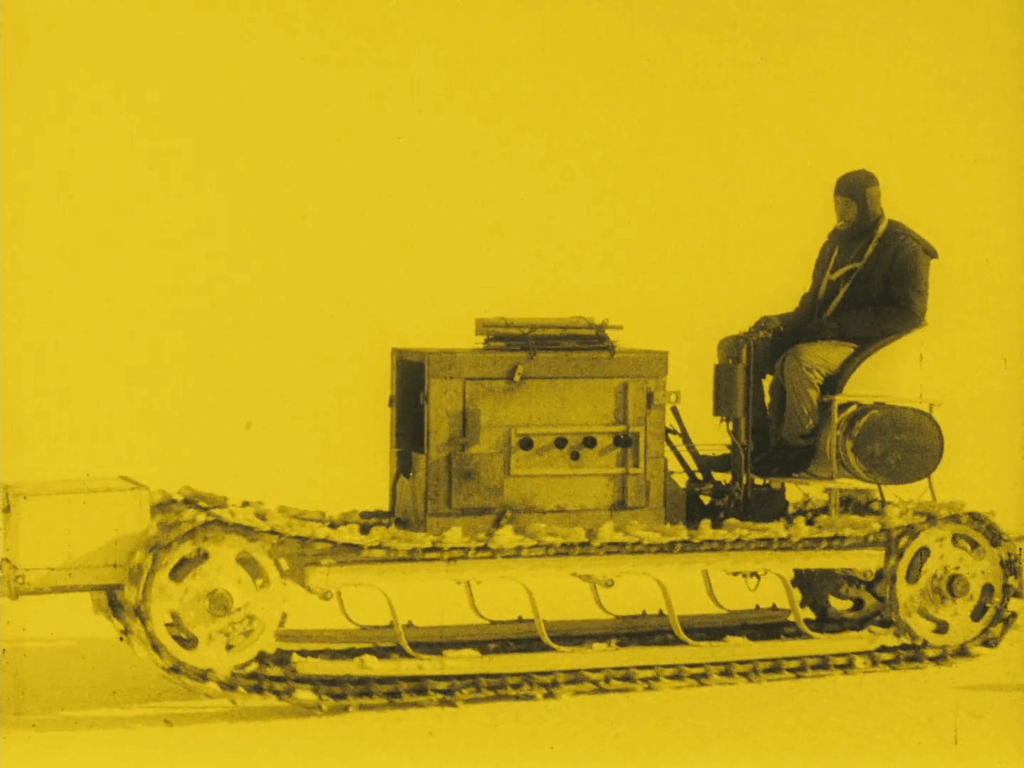

A rival team of Norwegian explorers, led by Roald Amundsen, beat Scott to the Pole by a month. Amundsen’s strategy varied from the elaborate designs of Scott’s operation: he used sled dogs, shorter routes, and leaner equipment, and his team returned with both the historic milestone and all 19 men in good health. Scott’s approach was more of an industrial operation than Amundsen’s streamlined conquest: Much of Scott’s trip took place by foot, supplies stored in man-hauled sledges. Horses that had no business in Antarctica pulled the sled during early stretches until the explorers killed them for food. Scott brought 65 personnel who thinned out across the journey, returning to base with empty sleds. The final group pulling a load of supplies in a sled across a glacier comprised five explorers. When they reached the Pole on January 17, 1912, they were devastated to find that they weren’t the first to make it. Scott and his team took a a photograph of themselves at the pole, five gaunt figures with frostbite-scarred faces, standing in front of a Norwegian flag like the losing team in some cosmic relay race. It’s a haunting image of catastrophic defeat, one with even more gravity since we know all five men were a few weeks from death.

Getting to the pole was just the beginning. The return trip — hundreds of miles back to base — was a march through an escalating series of calamities. The men were already broken, and then the weather turned, and then their bodies started giving out. One man fell and struck his head; he died shortly after. Another, Captain Lawrence Oates, so frostbitten he could barely walk and needed to lean on the sled to stay upright, sacrificed himself by stumbling out of the tent into a blizzard one night, hoping to give the others a better shot. The remaining three, including Scott himself, pressed on, praying they might be met by a dog team or support party, but no one ever arrived.

Scott and his two remaining companions kept crawling forward as best they could, their pace slowing with each mile, until finally they couldn’t go any farther. In the final days of March 1912, they pitched their tent and never left it. All three passed on March 29 (or maybe early March 30). In the cruelest irony of the entire expedition, their final resting spot was a mere 11 miles from a supply depot, almost in visible sight. When a search party eventually found them eight months later, frozen stiff in their sleeping bags, Scott had apparently repositioned the other bodies, suggesting he was the last to die. The ship went down, and the captain went with it.

We know all of this because Scott compulsively documented his journey. He journaled fastidiously, often eloquently, right up to his final breaths, leaving behind a record of the expedition’s highs, its many lows, and a final, painfully British elegy to the idea of noble failure as his farewell passage:

“We are weak, writing is difficult, but for my own sake I do not regret this journey, which has shown that Englishmen can endure hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last. But if we have been willing to give our lives to this enterprise, which is for the honour of our country, I appeal to our countrymen to see that those who depend on us are properly cared for.” – Scott, March 29, 1912

But this expedition had more than just a paper trail. Scott’s team had also brought along photographic equipment — including a cinematograph. And so, in addition to his words, we have images: photos of the crew before they departed, pictures of their winter-ravaged faces, and, eventually, the still frames of their final resting place taken by the rescue crew who discovered them eight months later. Scott didn’t make it back, but all of his records, his journals and photos, survived.

(One curiosity of the Terra Nova expedition is that it gained fame for the tragic story of its captain, but the expedition’s biggest legacy was scientific. Some geologic findings, including by Scott and his companions in their final days, provided fossil evidence that offered the concrete evidence to validate the theory of continental drift. Zoologists used footage and documentation of Antarctic animals to help build a better understanding of survival in the extreme cold.)

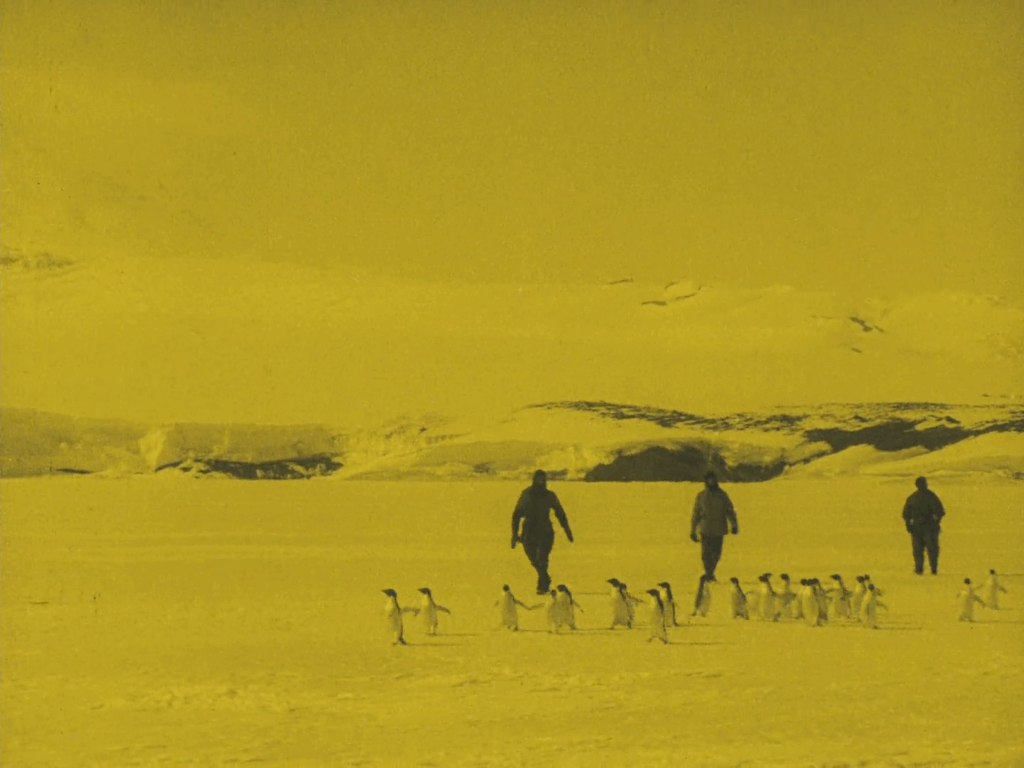

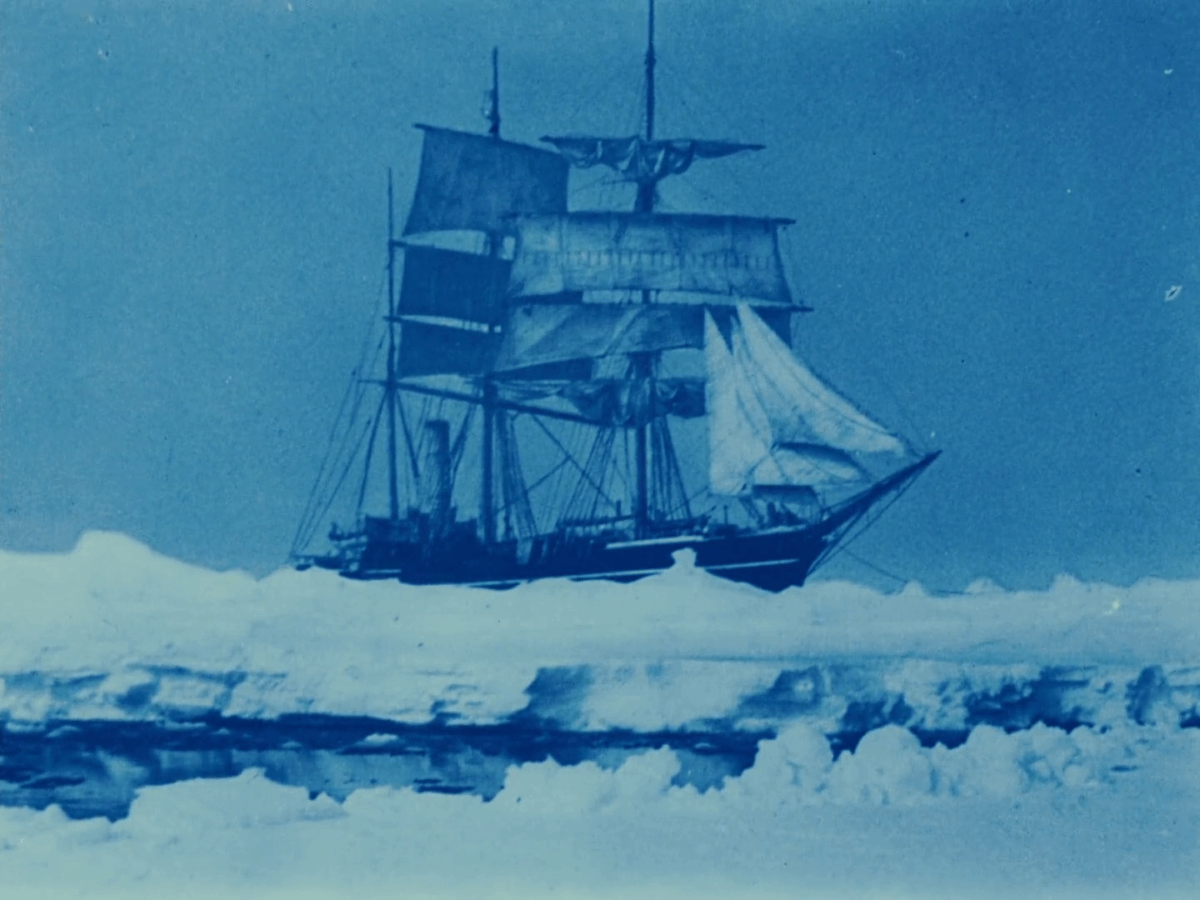

One person staffed on the Terra Nova expedition was Herbert Ponting, a gifted photographer and cinematographer who would become the first person to capture moving pictures of Antarctica. Ponting had serious visual instincts and a willingness to risk frostbite (and death) to get the right shot. He reportedly hoped to join Scott’s doomed push to the South Pole with camera in hand, but Scott left him at base camp. Instead, Ponting documented everything he could from the relative safety of Cape Evans: the arrival on Ross Island, the setup of the winter quarters, the local fauna, and the departure of the final group bound for the pole.

Eleven years after the expedition concluded, Ponting released The Great White Silence, a silent feature stitched together from reels and photos of the trip, mostly shot by him. The result is part nature documentary, part expedition travelogue, part newsreel, and part obituary. The film builds slowly, opening with scenes of shipboard camaraderie and Antarctic wildlife. Its final half hour is a montage of Scott’s photographs and diary entries from the captain’s last days, along with images of the discovery of Scott’s resting place. The closing segment hits like a hammer. Ponting wasn’t there for the end, but he curates its tragedy. He tells the story honestly and compassionately.

The press and critics gave high remarks to the film, but audiences didn’t show up. You’d think a national tragedy with built-in mythos would draw crowds, but 1924 Britain had moved on. World War I had come and gone; Scott’s brand of heroic fatalism may have felt more bitter than noble. Ponting’s clashes with Lieutenant Edward “Teddy” Evans — Scott’s second-in-command and a famed survivor of the expedition — surely didn’t help. Their falling-out over the use and control of the footage soured public support. In 1933, Ponting gave it another shot with a reworked edit of the material titled 90° South, this time with synchronized narration. That one flopped too. Ponting died two years later, broke and forgotten.

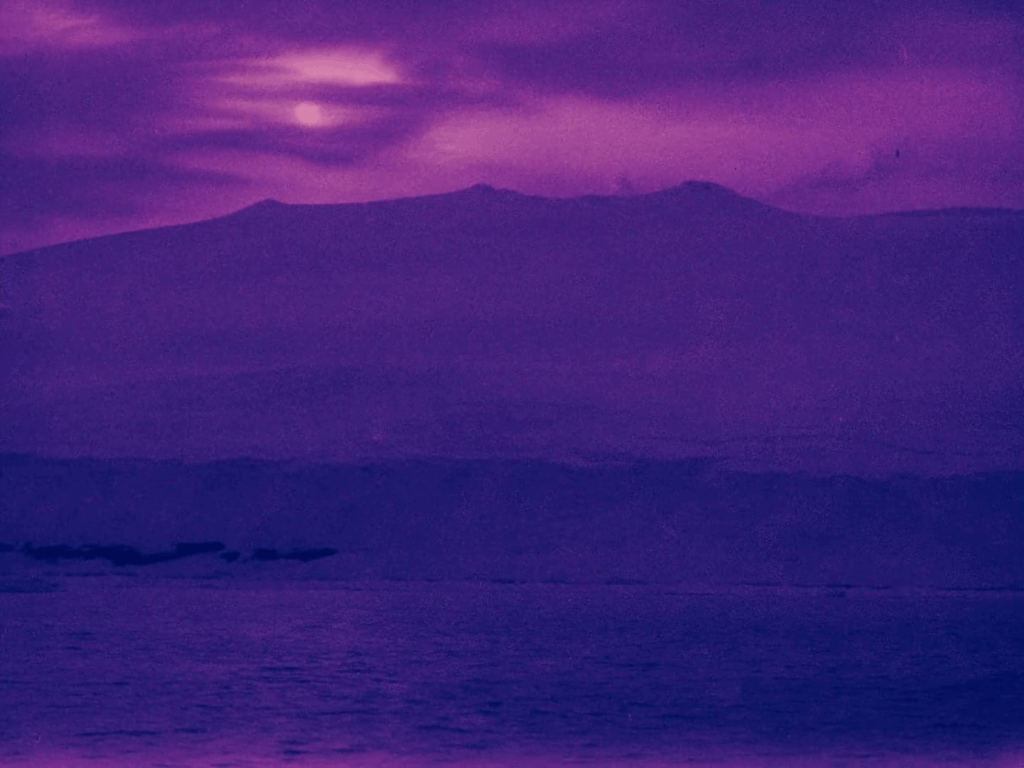

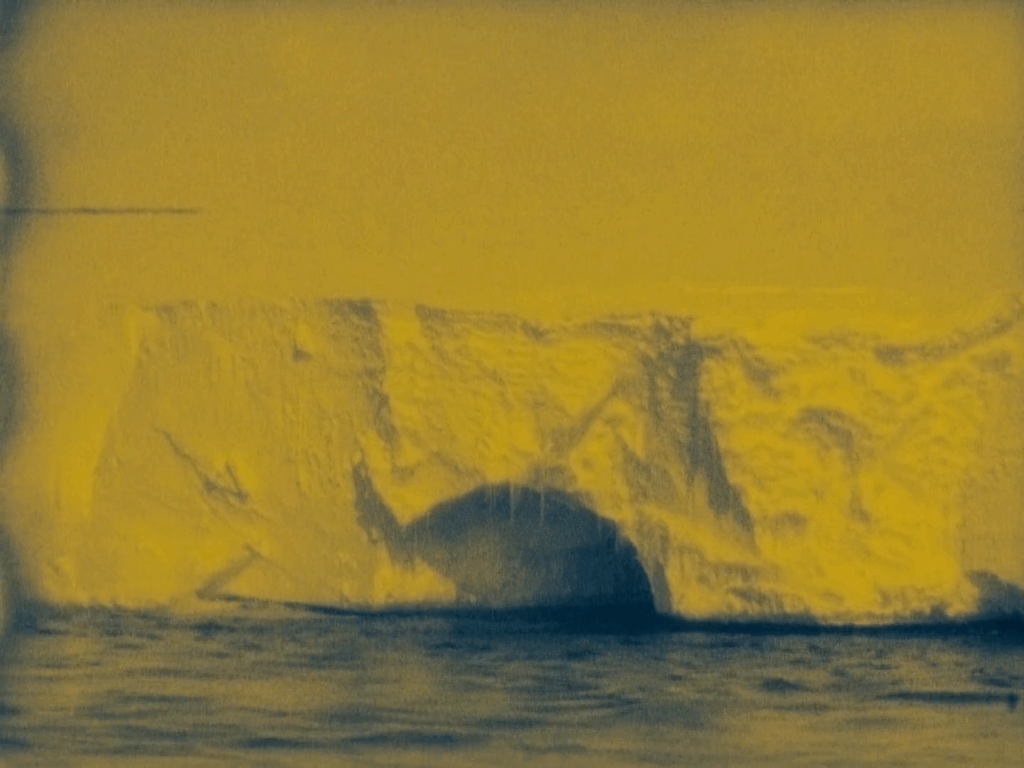

But the film and the footage survived. And in 2011, the British Film Institute restored and released The Great White Silence. The result is truly astonishing. This is one of the best restorations of any silent film I’ve ever seen — the footage is stable, crisp, full of contrast and texture, with the icy whites and inky shadows of Ponting’s original compositions lovingly preserved. The re-release earned rave reviews and helped reclaim Ponting’s legacy as a documentary pioneer. The film now holds a spot in every edition of 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.

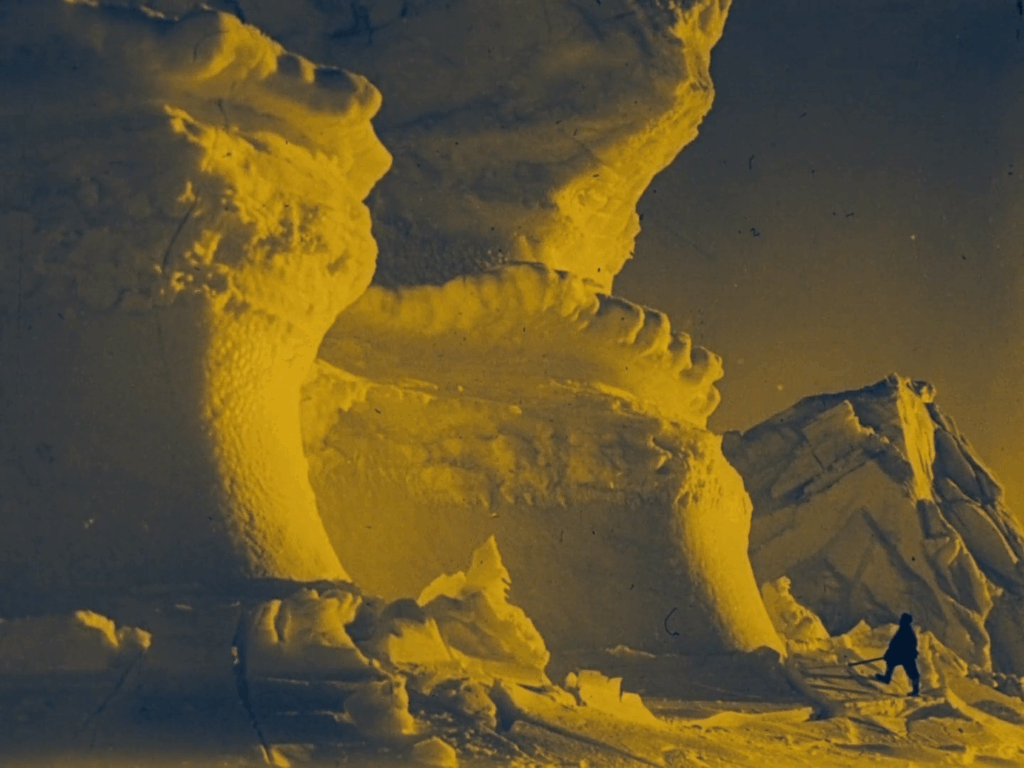

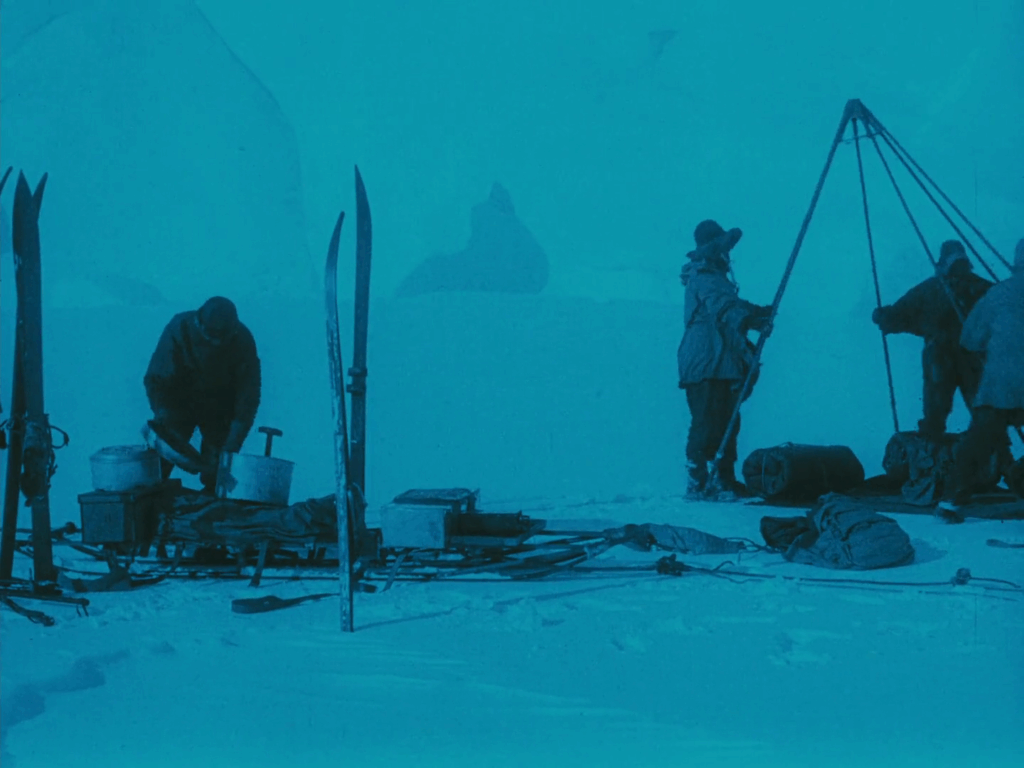

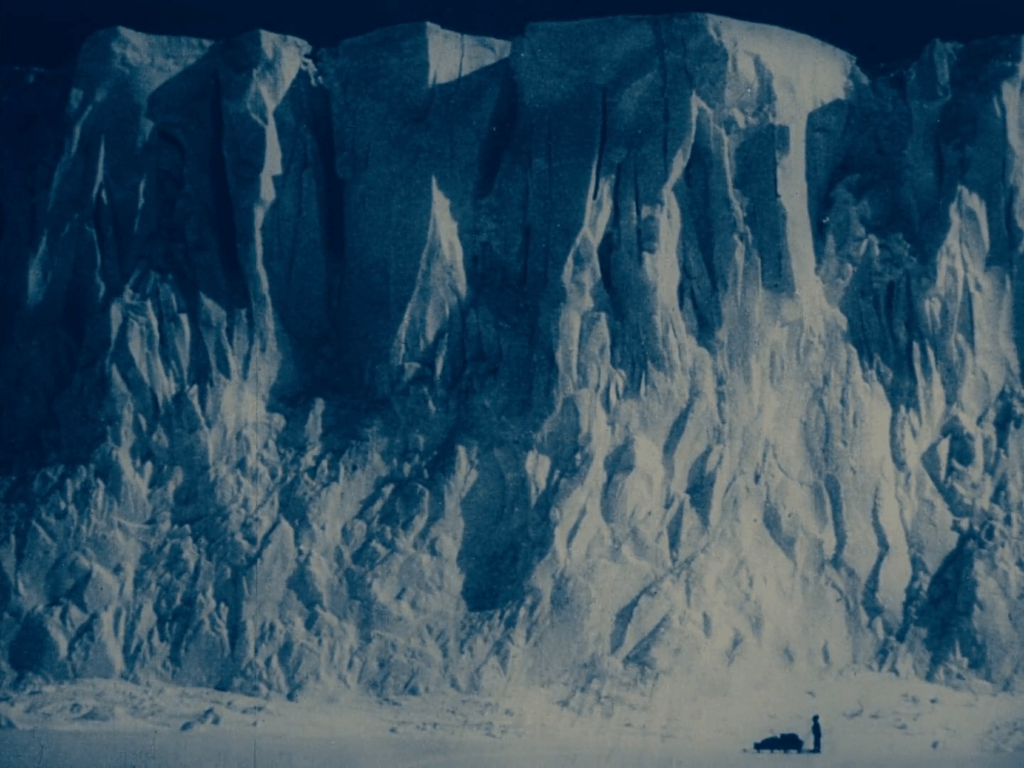

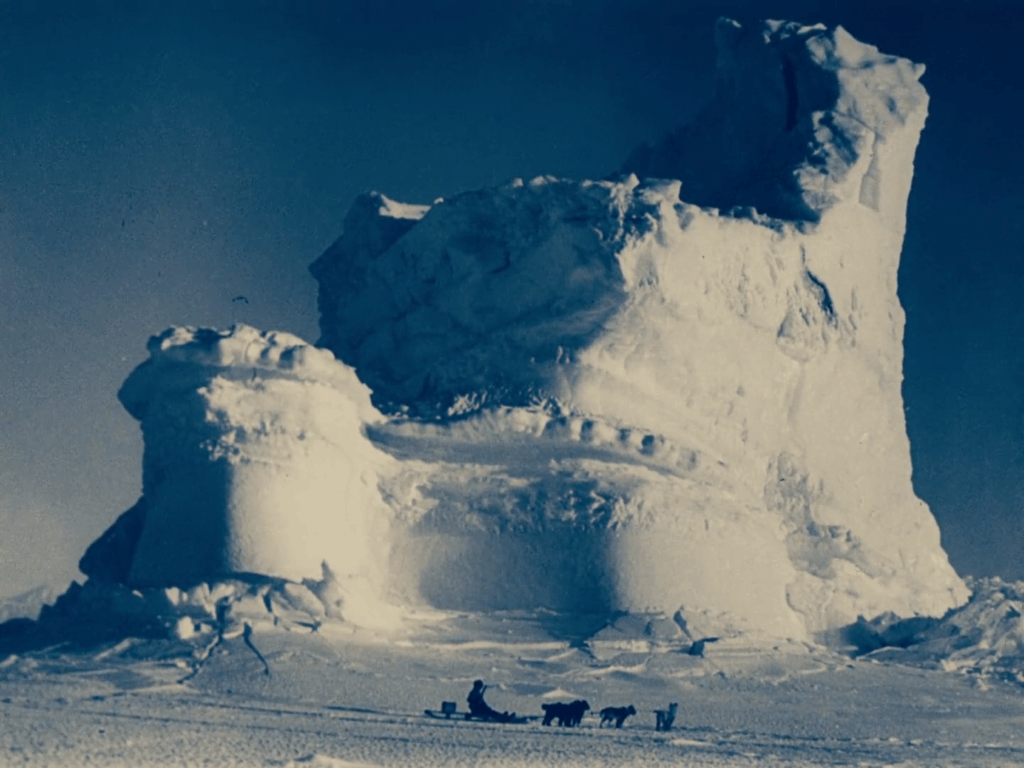

And honestly, the footage earns it. Set aside the dramatic last act for a moment: just the material of daily Antarctic life is remarkable. There’s a primal awe to witnessing Terra Nova nudge through ice floes, or seeing men in thick wool uniforms hoist crates and pitch tents against a wind that might kill them if they stop moving. It’s a true human frontier documented in uncommon detail.

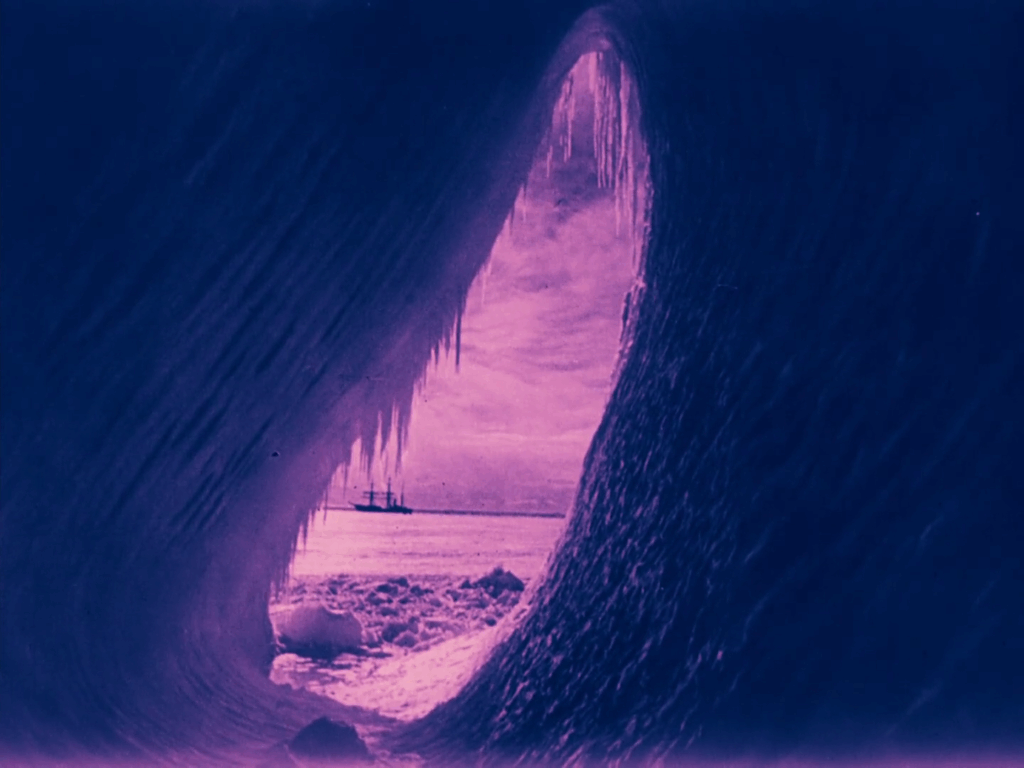

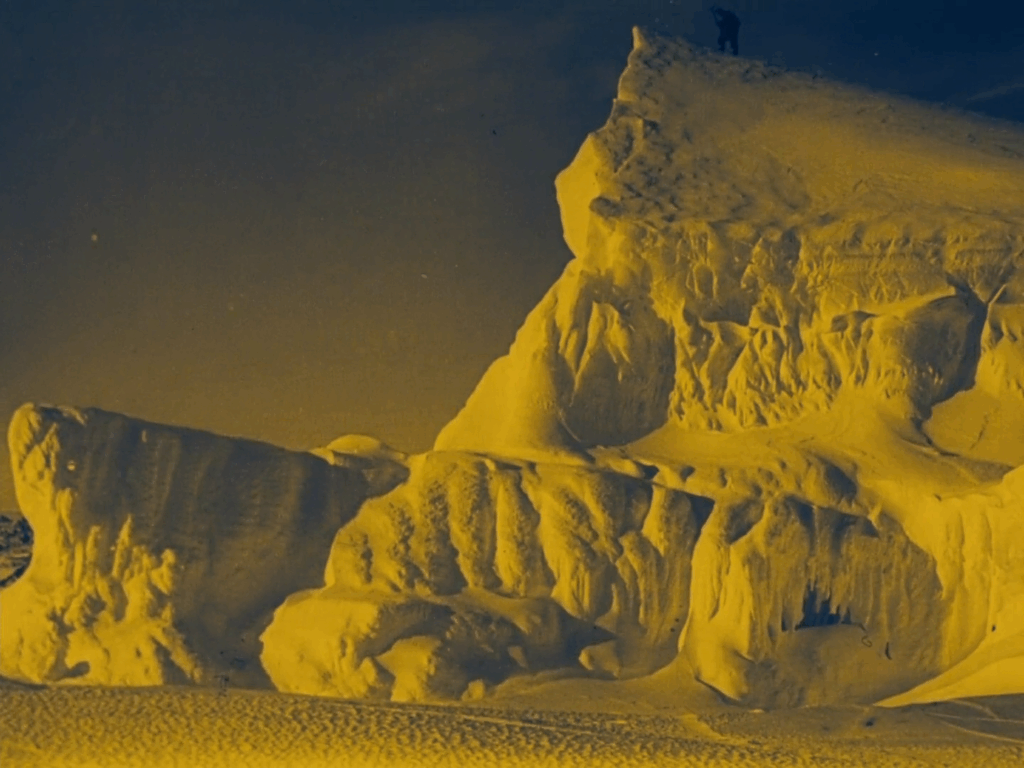

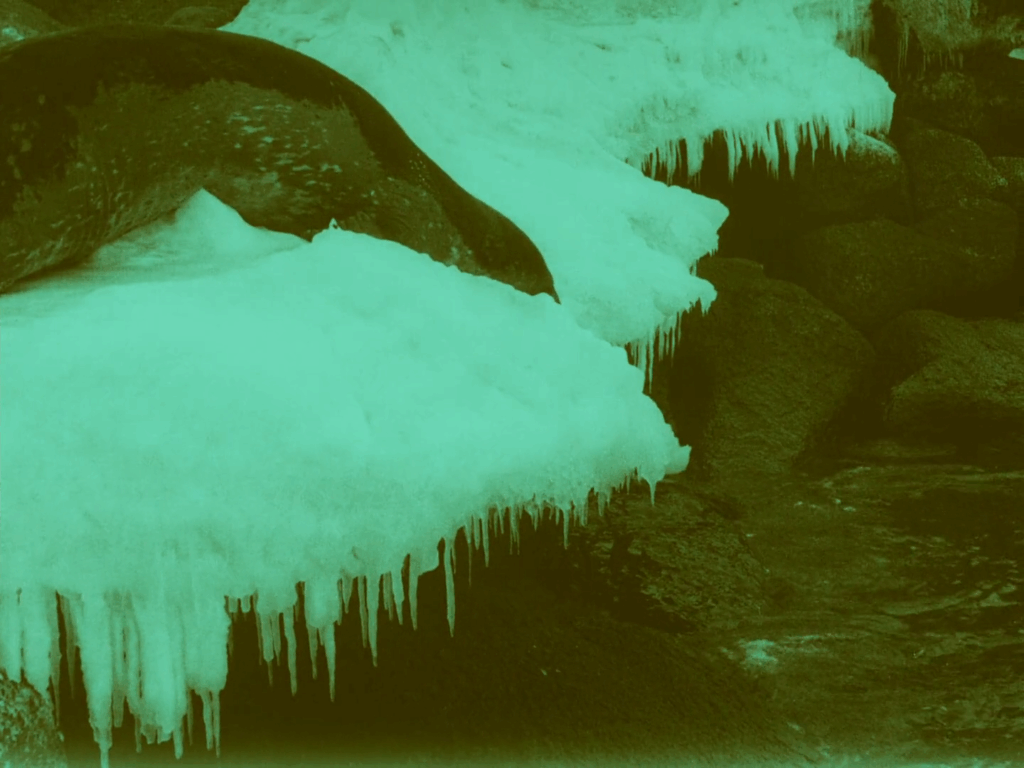

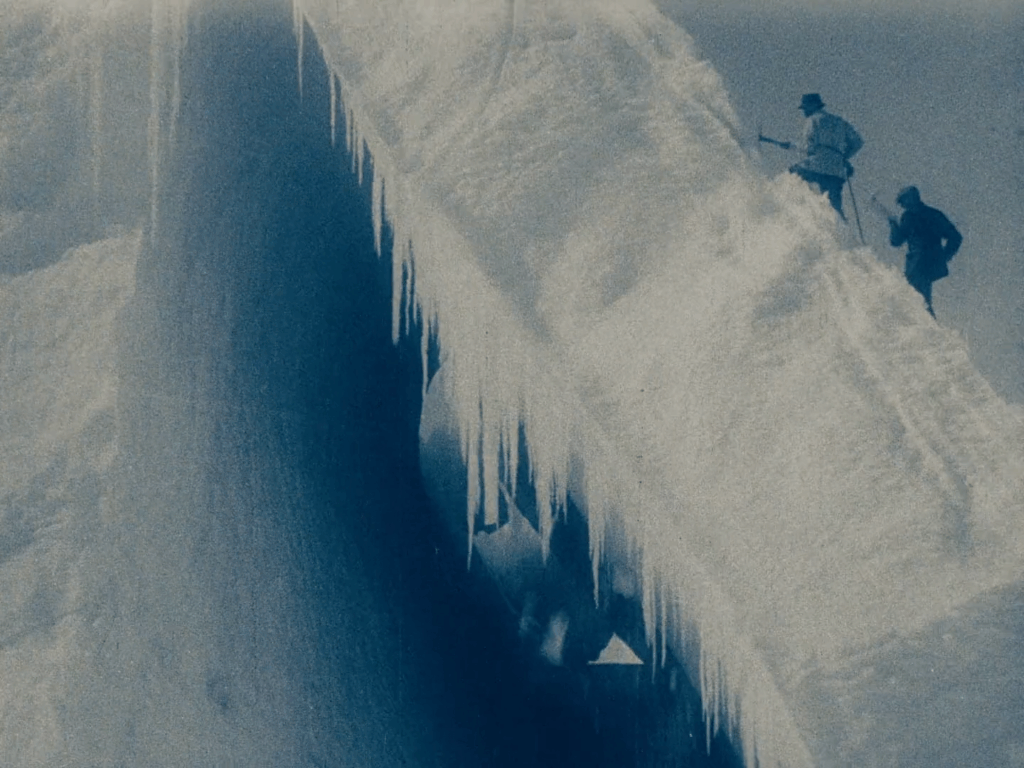

Part of the power of the images is in their portent and significance: this is the first time most of these settings and scenarios were ever filmed. But part of it is just Ponting’s eye. He knew how to compose an image of the jagged icescape, how to find dignity in posture and light. He nearly died more than once filming frigid waters, ice caverns, and angry mama seals. The man earned these reels.

Ponting also emerges from the film as a skilled editor and storyteller. The Great White Silence (a wonderful title, by the way) flows with a real sense of rhythm and structure, toggling between the sweep of the expedition and small, endearing interludes: a flash of a soccer game in subzero conditions, two penguins hatching, the offhand camaraderie of men trying to stay sane in extreme cold. The intertitles are well-judged, providing just enough context without tipping into sermon or self-congratulation. And when the film turns to its fatal endgame, Ponting lets Scott’s own words carry the weight. There’s reverence here, but not hagiography. He’s not exploiting the death of the explorers, nor whitewashing it into propagandistic valor. The grief is authentic but not maudlin, the story easy to follow, and the tone elegiac.

One irony of the film is that the footage which would have been the biggest novelty in 1924 now feels much more ordinary: the Antarctic animal life. We’ve since been gifted with decades of high-definition nature footage by world-class documentary teams: We’ve followed penguins through mating seasons and watched orcas breach in IMAX. So Ponting’s scenes of seals and skuas and emperor penguins can’t help but feel a little quaint. But the footage still offers excitement in watching these animals up close, especially in knowing that this was the first time anyone had caught them on film, that the man behind the camera put his life on the line to get the shots.

The dark final half hour is indeed the most powerful portion, but the most limited in terms of footage. Ponting assembled most of it from still photographs and intertitles quoting journal pages, but the sequence has real tension. Ponting includes footage of sled-lugging and camp setup shot during training exercises or later recreation, and it gives a sense of what the trek to the pole must have felt like. And in those last few minutes describing the final days of Scott and his team, the film has real danger and gravity, like the end of Grizzly Man.

For all its weight, the ending bears an unanswerable what-if: What if Scott had invited Ponting to join the polar expedition team? Would we have footage of the moment they discovered Amundsen’s flag? Would we have seen the frostbitten agony up close, the faces charred by cold and disappointment, bodies growing gaunter by the day? Maybe it’s for the best we don’t. Maybe it’s enough that the film shows us the hopeful departure and leaves the failures and downfall to text and snapshots. Still, it’s hard not to wonder what Ponting might have captured had his cinematograph traveled further south.

The 2011 restoration includes a modern score by Simon Fisher Turner, and it’s an outstanding, fascinating exercise of dissonance. Turner doesn’t go for sweeping strings or martial grandeur. He instead opts for something atmospheric and mournful, occasionally drifting into ambient dreaminess. It undercuts any lingering notions of glory, particularly against the cheerful footage in the opening half of the film, and instead gives The Great White Silence a ghostly, haunted texture, as though the whole expedition is playing back from beyond the veil. It feels spiritually in tune with what the footage became: not a record of triumph, but an artifact of loss. A eulogy rendered in light and grain.

The Great White Silence is a stunning document. It certainly has some rough edges and historical eccentricities: for example, the pet black cat’s name is a racial slur — yes, that one. The stretch of nature footage towards the middle drags on a bit, too. But the film remains riveting. Nanook of the North is the more famous of prototype documentaries of the era, and it’s an obvious comparison to this because both capture life in the intense cold. But The Great White Silence is the better film in every meaningful sense: richer, bolder, sadder, more visually striking, and more honest in tone. It’s a rare thing: a work of real-life cinematic archeology that remains worthwhile and moving a century later.

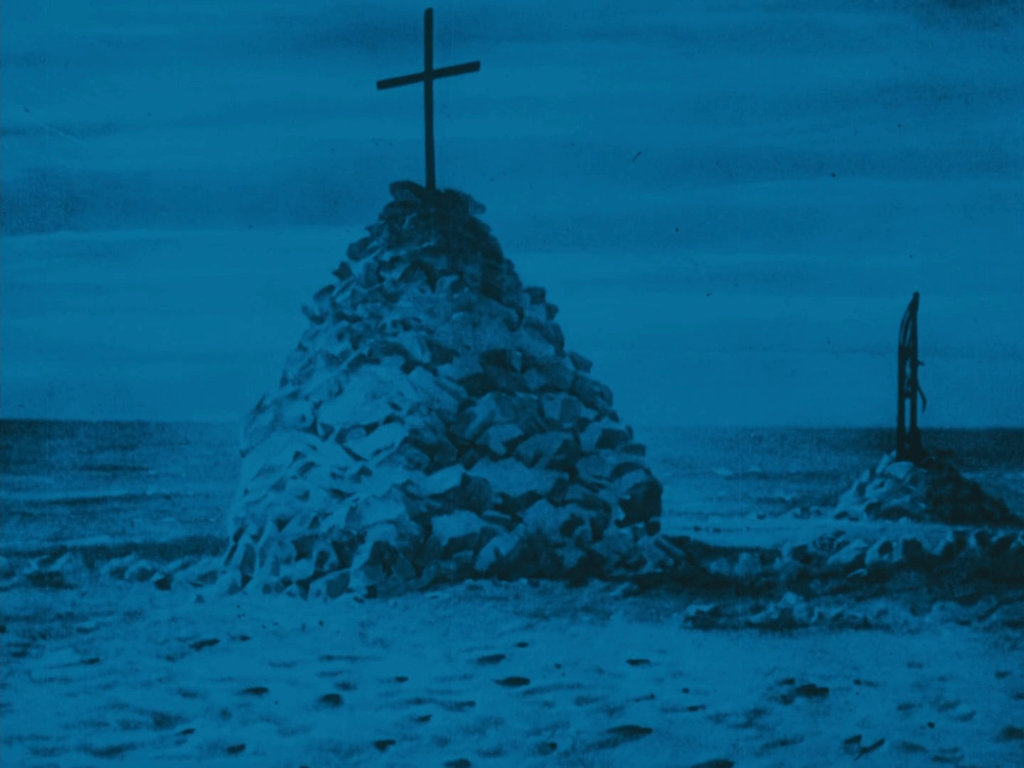

Here are a few more striking images from The Great White Silence:

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “The Great White Silence (1924)”

Tremendous write-up, Dan! I’d never heard of this, and now I’m champing at the bit to watch it!

Thanks Andrew!

The film is in the public domain (though I’m always unclear how modern restorations are impacted by those rules) and you can find the whole thing linked in Wikipedia and on YouTube in its 2011 restoration glory:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7fcAyyNnuI8

Just to answer that question, new restorations are 100% not copyrightable. It’s probably the good and right thing, but it does pose problems for monetizing public domain films, which in turn poses problems for having remotely decent versions of public domain films, or even ANY version of public domain films. And of course as time marches on there’ll be increasing amount of stuff that we can’t really hope will ever be restored or put in HD or even released.

Addendum: the scores on silent films will usually be under copyright, however (that is, so long as they were written after 1928–nevertheless, even though this isn’t afaict the done thing with silent films, new recordings of the original accompaniments or synch-score tracks *would* be copyrightable, I guess in the same way a shot-for-shot remake of a public domain film would be copyrightable; I kind of expect this is more of an unintended consequence of a provision that I think was always more of a sop to the classical music industry).

This movie sounds cool btw.

Aha. There you go. I see what you mean about the commercial viability of film restoration dilemma. As with many problems I’ve encountered in life, the solution seems to be that I need to win the lottery, at which point I will fund silent film restoration with no concern for profit.