North of Hollywood, west of Hell

“The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”

–W.B. Yeats, “The Second Coming,” 1919

“Well, I’m going to be a famous jazz musician. I’ve got it all figured out. I’ll be unappreciated in my own country, but my gutsy blues stylings will electrify the French. I’ll avoid the horrors of drug abuse, but I do plan to have several torrid love affairs, and I may or may not die young. I haven’t decided.”

–Lisa Simpson, “Separate Vocations,” 1992

In 2016, London-based photographer and sculptor Jason Shulman undertook an experimental project that would go on to be exhibited at the Cob Gallery under the title “Photographs of Films.” The premise of the series was simple: Shulman would set up a camera in front of a film as it played and capture its entire runtime (minus titles and credits) as a single, long exposure photograph. The hundreds of thousands of individual frames that make up a feature-length movie were, in effect, superimposed and pressed together to create a single impressionistic image.

The pictures Shulman derived from his chosen subjects are striking; catnip for anyone who’s interested in cinema for its abstract qualities of composition and framing. (Some of my favourites include his 2001: A Space Odyssey, where the phantoms of Douglas Trumbull’s production design are discernible through Kubrick’s glacial long-takes, or his Under the Skin, which derives from Glazer’s movie the haunting image of one dark figure looming over another’s supine body.)

I bring this up because – to the best of my knowledge – Schulman has never used a Nicolas Winding Refn movie as a subject, and I bet if he ever did, the results would be spectacular.

[Winding Refn] occupies a niche at the intersection of arthouse and grindhouse.

Well, one of his late-stage movies, at any rate. Winding Refn’s career has charted a long course to get to where it is today, where he occupies a niche at the intersection of arthouse and grindhouse. He’s a unique specimen of provocateur, puckishly courting controversy while demonstrating a fearsome command of the frame. He makes exploitation movies that look like spreads in glossy lifestyle magazines, his shots so freighted with potent imagery that they tempt the unsuspecting viewer to dive in, searching for meaning, and drown.

Born in Copenhagen in 1970, he was raised in a family steeped in the tradition of cinema. (His mother Vibeke Winding has worked as a cinematographer as far back as the late 60’s, and his father Anders Refn is blue-linked on Wikipedia; he has an incredibly robust résumé as an editor spanning seven decades, which includes a fruitful partnership with Lars von Trier.)

By dint of his upbringing, perhaps it was inevitable that Nicolas Winding Refn would work in movies, but it wasn’t inevitable that his career would chart the course that it did. He got his start directing Pusher in 1996, a crime movie focusing on the lives of low-level Copenhagen reprobates, shot with vérité intensity and written with a lot of vulgar, rapid-fire, button-pushing dialogue exchanged between its lowlife protagonists (including a star-making debut from Mads Mikkelsen, as the skinheaded delinquent Tonny). It’s full of piss and vinegar and kinetic energy, relishing in the sordid and the transgressive; a Danish entry in that early, 1990s wave of Tarantino-likes (see also: Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting, Tom Tykwer’s Run, Lola, Run, Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock, & Two Smoking Barrels, etc.). It’s visibly the work of a snotty, disillusioned twenty-something who, according to Wikipedia, “attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts but was expelled for allegedly throwing a chair into a wall.”

Pusher was a local hit when it came out, but Winding Refn struggled to consolidate its momentum right away.

Pusher was a local hit when it came out, but Winding Refn struggled to consolidate its momentum right away. His sophomore outing, the 1999 drama Bleeder, languishes in obscurity to this day (to the extent that it’s even quite hard to find). His first English-language feature, 2003’s Fear X (co-scripted with American novelist Hubert Selby Jr., one of the writer’s last works before he passed away in 2004), was a commercial catastrophe that almost destroyed his career, bankrupting his production company Jang Go Star and leaving him in debt to the tune of a million dollars while his wife was pregnant with their first child. There was even a documentary about it: 2006’s Gambler, directed by Phie Ambo.

This is a real shame, not least because Fear X is actually a really good movie, unappreciated in its time. John Turturro gives a harrowing performance as a small-town Wisconsin mall cop hunting for clues to the reason for his pregnant wife’s murder. The unbearably cold-looking scenes set in a midwestern midwinter are complemented by the austere, frigid quality of the camera movement, and the acting, and the dialogue. It presents a universe where every emotion is guarded and reticent. And then there’s the ending: a weird, anti-cathartic non-conclusion, suggesting that the search for meaning is fruitless.

Fear X is the earliest glimpse of the filmmaker that Winding Refn would grow into.

In time, NWR would claw his way back out of financial ruin. The process involved making two sequels to Pusher, a proposition that initially repulsed him, despite how well-received Pusher II and Pusher III ended up being (as well as a couple of episodes of Agatha Christie’s Marple for the BBC, of all things). He went on to make Bronson, a blackly comedic biopic of legendarily violent prisoner Michael Peterson that put Tom Hardy on the radar of a lot of casting directors, and Valhalla Rising, a bleak, mud-spattered, Viking-era riff on Aguirre, the Wrath of God.

It was 2011’s Drive, though, that really put him on the map as a major international talent, earning him the Best Director award from Cannes, followed by a nod from the Academy Awards for Best Sound Editing, and grossing $79 million against a $15 million budget. It was an enduring cult hit, a pivotal moment in star Ryan Gosling’s career, and arguably the cultural watershed that popularised synthwave as a music genre in the 2010s. Adapted from James Sallis’s 2005 novel of the same name, Gosling plays an anonymous stuntman with a side-hustle as a getaway driver for L.A.’s criminal element, whose romantic infatuation with his neighbour (Carey Mulligan) is complicated when her debt-laden husband (Oscar Isaac) is released from prison.

Drive’s story is a solid, pared-down neo-noir – tense and twisty, with a surprisingly warm romantic streak – but it was the style that caught audiences’ attention far more than the substance. You only need to see the first few seconds of the movie to recognise why it got the Best Director nod that year, beating out other In Competition offerings from the likes of Lynne Ramsay, Pedro Almodóvar, and Terence Malick (whose The Tree of Life won the that year’s Palme D’Or). It was with his eighth feature that Winding Refn established himself as the world’s foremost living director of surfaces; of streetlights reflected in car windscreens; of the scintillations of neons signs through motel windows; of the minutest flickers of Gosling’s eyes in the actor’s impassive, porcelain face. Winding Refn curated his frame with a meticulous, Wes-Andersonian attention to detail.

Practically every shot in Drive gives the viewer something to keep their eyes busy; nodes of light and colour forming patterns that wash across the frame like an impressionist’s canvas. Silky-smooth dolly shots and ultra-high-frame-rate slow-motion punctuate beats of extreme violence, giving them a composed, dreamlike quality outside of time. I was going to describe the way that Winding Refn poses his actors as “painterly,” but truthfully, the medium that feels closer to the mark is sculpture. The stillness of the performers in Winding Refn’s frame is always in tension with the nature of film as a temporal medium; for seconds at a time, his actors stand, impeccably frozen, and their capacity to move is braced against the fact that they don’t.

Drive is perhaps the most accessible instance of NWR’s house style; the movie struck just the right balance between his formal tics and a straightforward, compelling bit of genre fiction that global audiences could get on board with. (And, look, I think global audiences were right to do so. Drive is hands-down NWR’s best feature; I personally think it’s a masterpiece.) And he was presented with opportunities to parlay Drive’s success into mainstream, A-list status, being approached to direct a Barbarella remake, Wonder Woman, and even the James Bond entry Spectre. He turned down those shots at big-budget fame and fortune (admirably, in my opinion) and focused instead on developing his own original projects.

2013’s Only God Forgives and 2016’s The Neon Demon both doubled down on the kind of fussy, curated framing that Drive introduced to the world, in the absence of the 2011 movie’s relatable characters and propulsive plotting. Box-office and critical responses ranged from indifferent to repulsed, but Winding Refn seemed undeterred. He’d found his voice as a filmmaker, at last, and he pursued it with absolute confidence and self-assurance.

Which leads us, at last, to the nominal subject of this article: Too Old to Die Young, the limited series he directed for Amazon Prime, released on June 14th, 2019.

If you’re wondering what all that preamble was for: well, dear reader, I marathoned all of Nicolas Winding Refn’s works in order in July of 2025, and arriving at Too Old to Die Young, I had the distinct impression that everything NWR had done in the first quarter-century of his career, prior to 2019, was a warm-up for this show that Amazon buried and no-one saw. I binge-watched all thirteen hours of the series in the course of a week, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since. If one were to collapse all ten of his films together, Shulman-like, starting from 1996’s Pusher and ending with 2016’s The Neon Demon, they would reach critical mass, achieve runaway nuclear fusion, and the resultant city-levelling explosion would be Too Old to Die Young.

The pitch for the show makes it sound fairly straightforward. NWR co-wrote the story with Ed Brubaker, the multi-Eisner Award-winning comic book author. (He has multiple acclaimed, noir-themed graphic novels under his belt, but Brubaker is probably best known as the writer who reintroduced Bucky Barnes – Captain America’s original sidekick from the 1940’s – as the Winter Soldier in his 2005 – 2009 run working for Marvel.) Miles Teller, still in the afterglow of his terrific performance in 2014’s Whiplash, would play the lead role.

In a bullish streaming market, it’s easy to imagine what Amazon thought they were commissioning: a prestige, slick, stylish, LA-set neo-noir with lots of sex and violence and sexy violence, with a hot young leading man, a writer indirectly responsible for one of the most successful appendages of the MCU, and a director who inaugurated a whole decade of LA retro-chic. What could go wrong?

“… it’s easy to imagine what Amazon thought they were commissioning…”

Well: about that…

Teller plays Martin Jones, a junior LAPD officer who we’re introduced to while on patrol with his partner, Larry (Lance Gross). In the course of their evening, Martin listens without comment while Larry muses aloud about his plans to cover up his extramarital affair by murdering his mistress, and conspicuously fails to intervene when Larry intimidates and extorts a woman he pulls over on a traffic stop. This appears to be a pretty ordinary night for both of them, right up until the moment Larry is unceremoniously shot to death by Jesus Rojas (Augusto Aguilera) on the sidewalk, while taking a selfie to send to his side piece/intended victim. Martin fires after the assassin, but Jesus gets away.

(Note: the character’s name is spelled “Jesus”, not “Jesús”, as gringos like me might expect it to be. In paragraphs to follow, when you encounter sentences like, say, “Jesus’s wife makes him up to look like his dead mother and sodomises him with the handle of a bullwhip,” you’re just going to have to trust me that I’m not blaspheming on purpose.)

Larry’s slaying, it transpires, was an act of revenge; Jesus killed the cop who he thought was responsible for the death of his mother. However, he got the wrong cop; Martin was the one who actually killed his Mum, during a job he and Larry carried out together on the orders of local mob boss Damian (Babs Olusanmokun).

Martin, consequently, is locked into Damian’s employ as a hitman; a situation complicated still further by his relationship with Janey (Nell Tiger Free), the 17-year-old he counselled when he was the first responding officer after the death of her mother in a traffic accident.

Episode 1 of Too Old to Die Young, titled The Devil, through the entirety of its lugubrious 93 minutes, presents Miles Teller’s character as an ephebophile, as a corrupt cop, as an unrepentant murderer, and as a robotic, unsympathetic dork with no social graces whatsoever. He also has a habit of spitting, as a way to punctuate breaks in conversation.

A large swath of this first episode is given to Martin meeting Theo (William Baldwin), Janey’s sleazy, immensely wealthy father with his own off-putting, phlegm-related habit: he’s constantly sniffling and snorting, never quite comfortable with whatever’s going on in his nose. (There’s a fairly intuitive reason for why the character’s septum might be damaged.) The scenes set in Theo’s house – which include Janey’s bedroom, every inch a girl’s room, full of stuffed animals – play out like the kind of awkward meeting with a father-in-law you might see in a sitcom.

It’s hard to say what’s more upsetting; that Too Old to Die Young’s main character is in a sexually active relationship with a teenager, barely half his age, or that said teenager’s dad is apparently OK with this state of affairs.

That’s all in the first episode, and if you can believe it, The Devil is the closest that Too Old to Die Young ever gets to feeling like a “normal” piece of crime fiction.

The bulk of the show’s narrative is split between Martin’s story and Jesus’s. As it transpires, Larry’s assassination was an initiation of sorts for Jesus. He was raised north of the border by his mother, Magdalena (Carlotta Montanari); at the beginning of the show, he only speaks very shaky Spanish. His maternal uncle, the terminally ill cartel boss Don Ricardo (Emiliano Díez) doted fiercely on his sister, and rewards Jesus by taking him into his own family as a surrogate son.

Episode 2 (titled The Lovers) is set mostly within the confines of Ricardo’s compound in Mexico, the Don’s health slowly failing, regaling his family with long, slurred anecdotes of his cherished memories of Magdalena, and of seeing Pele play football. Jesus butts heads with his cousin, the hotheaded and belligerent Miguel (Roberto Aguire), primed to succeed Ricardo as head of the cartel.

Meanwhile, we’re also introduced to the profoundly mysterious Yaritza (Cristina Rodlo), the beautiful, near-mute woman who emerged one day out of the heat-haze of the desert, who Don Ricardo accepted into his house, and who occasionally reads the tarot for him. Jesus is infatuated with her, and in time, she becomes his wife. Little does he know that his bride-to-be is leading a double life; she’s superhumanly gifted in combat, and is covertly liberating the cartel’s sex-trafficking victims by night. She’s spoken of in whispers as a local folk heroine, referred to by the amazingly metal title “La Alta Sacerdota de la Muerte” (“The High Priestess of Death.”)

Quick aside: the attentive reader might already have noticed, but Too Old to Die Young’s episode titles are all derived from names of cards in the tarot deck. I, personally, am not a superstitious person, and I don’t place a lot of significance on the mystical, unquantifiable relationship between playing cards and outcomes in our shared, material universe.

But NWR is, and does. Notably, he’s good friends with Alejandro Jodorowsky, the Franco-Chilean firebrand and self-reported kinda-maybe-rapist who directed El Topo and The Holy Mountain, wrote my favourite comic book ever, and is generally the old-school kind of iconoclastic, disruptive, hashtag-problematic creator that NWR styles himself as.

In My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, the 2014 documentary made by NWR’s wife Liv Corfixen, Jodorowsky provides Winding Refn a tarot reading in the course of the production of Only God Forgives. This fascination with divination – and esotericism more broadly – is by all accounts sincere, and suffuses Too Old to Die Young throughout. (We’ll come back to that.)

A reasonable viewer’s expectation after the first couple of episodes would be that the enmity between Martin and Jesus will be the focus of the rest of the series – such a viewer will learn the hard way that Too Old to Die Young has no interest in being reasonable. The two lead characters’ paths do eventually reconverge, but it’s a long, winding route to get there. In the meantime, Martin is promoted from a beat cop to a homicide detective, and during an investigation into the death of a known child predator, he stumbles across Diana DeYoung (Jena Malone), a wealthy hippie working as a victims’ advocate in the California penal system, and Viggo Larsen (John Hawkes), a retired FBI agent caring for his senile mother even as he himself is dying from terminal cancer.

This fascination with divination – and esotericism more broadly – is by all accounts sincere, and suffuses Too Old to Die Young throughout.

Diana and Viggo have embarked together on a two-person crusade of retributive murder, tracking down and killing child molesters who’ve eluded justice, on behalf of the victims and their families. Martin tracks down Viggo easily enough (by the vigilante’s own admission, his illness has made him sloppy), but rather than arrest him, he opts to team up with them instead. Increasingly alienated from his job – both the legitimate and corrupt aspects of it – Martin leverages his work with Damian, cherry-picking targets he feels best deserving of death.

That’s quite a lot of plot that I’ve just outlined, and if you’ve been paying attention, then I’m sorry, because very little of it ultimately matters. There are a lot of answers to the question “what is Too Old to Die Young about?” and almost none of them involve frivolous, superficial things like “stakes” or “characterisation” or “conflict.” Recapping the events of the show does less than nothing to elucidate the experience of watching it.

If you’ve never seen a Nicolas Winding Refn movie before, then:

A: Mother of God, don’t start with Too Old to Die Young, are you crazy? You have to graduate to this shit. Start with Drive, then progress to Only God Forgives, and if you’re still on board then maybe you’re ready.

B: There’s a very specific cadence to the way that he frames and blocks his shots; to the way his characters exchange dialogue; to the performances he asks of his actors.

His visual language is characterised by stasis and inertia. The camera is either utterly still, or else moves by such slight increments that it only makes the stillness more noticeable. (When a shot pans or zooms slowly enough that the second-to-second difference is only just noticeable, the viewer’s eye is guided to the edge of the frame, paying attention to the regions of mise en scène crawling out of view. It turns you into a suspicious viewer.)

Similarly, the visual elements within the frame are not dynamic. If it’s a close-up of an actor’s face, the actor will hold their head unnaturally still, their stoic expression unvarying; the slightest twitch of the eyes or lips is a big deal. If it’s a medium shot or a long shot, the players in view will stand like statues, each waiting their turn to do anything so dramatic as lift a glass or scratch their nose.

His average shot length isn’t actually that long. In the case of Episode 6, The High Priestess (a representative sample for the series), I counted 333 cuts in total, in the course of 88 minutes and 48 seconds (excluding title cards and credits). That makes for an average shot duration of 16 seconds. By most standards, that’s pretty long, but it’s not outlandish; we’re not quite in Tarkovsky or Béla Tarr territory. However, whenever he does cut, the cut is always conspicuous. No invisible continuity editing; it’s always one fussed-over, painterly image being abruptly swapped for another.

And then there’s the dialogue, which has the same deliberate lack of flow and seamlessness as the editing. Here’s a sample from Episode 5 (The Fool) to give you a taste. In this scene, Martin is working to infiltrate a gang of snuff pornographers (using “Kevin” as an alias), introducing himself to them at a booth in a mostly empty dive bar:

WENDY: “Would you like to sit?”

MARTIN: “Yeah. Thanks.”

(Wendy shifts along the couch and Martin sits.)

(6 second pause)

ROB: “I’m Rob, that’s my brother Stevie. That’s Wendy. This is Sandy.”

MARTIN: “It’s nice to meet you guys.”

WENDY: “Mm-hm.”

(5 second pause)

ROB: “What brings you to Albuquerque, Kevin?”

(4 second pause)

MARTIN: “I’m a salesman.”

(7 second pause)

STEVIE: “What do you sell?”

(7 second pause)

MARTIN: “I’m not a salesman.”

(Everyone laughs)

MARTIN: “I don’t know why I said that.”

THE WHOLE SHOW IS LIKE THIS.

You know how Robert Altman movies famously feature chaotic, motor-mouthed dialogue, characters talking over each other to the point that the words become hard to make out? NWR is like the anti-Altman when it comes to dialogue. It is impossible to imagine any real human conversation playing out according to the rhythms in this scene. It would be unbearably awkward at best; at worst, Martin would be outing himself as an astonishingly poorly trained undercover cop, and his interlocutors would immediately shoot him to death.

The weird, off-kilter tempo of the dialogue and the editing is underscored by the sound design. During the scene transcribed above, for example, there’s a country ballad playing in the background of the dimly lit bar, and in every yawning gap between lines, you notice it. This sort of auditory ambience is present in any given scene; if it’s not diegetic music, then it’s the sound of traffic, or the wildlife of the Mojave desert, or the rantings of a radio shock-jock. Persistent reminders of a larger universe, out of focus, churning on, indifferent to whatever’s happening here in NWR’s minutely controlled dioramas.

The cherry on top of this aesthetic is Cliff Martinez’s soundtrack. NWR’s collaborator through thick and thin since Drive, Martinez gilds the elaborate visual language with warbling, trilling synth swells. At times, the score throbs with rhythmic, pulsating bass; at others, with spacey, psychedelic theremin warbles. If the visuals, dialogue, and acting didn’t already tip Too Old to Die Young into the realm of surrealism, the music is the conclusive nudge.

“Drone” is a word I’ve occasionally heard used to refer to the style of filmmaking Winding Refn deploys in Too Old to Die Young. (Or else its conjugation, “droning.”) It’s not necessarily being used pejoratively; rather, it’s used to liken Too Old to Die Young to the Drone genre of music, typified by artists like La Monte Young, Godspeed You Black Emperor! and Sunn O))). An avant-garde variant on rock and electronic music, Drone is a specific type of minimalism, using the sheer duration of sustained notes and tones to achieve a kind of mesmeric effect.

You’ve heard of “mumblecore” cinema. Well, here’s “dronecore”

You’ve heard of “mumblecore” cinema. Well, here’s “dronecore”; an aesthetic that prompts the viewer to search the frame for the smallest shifts and deviations against a static backdrop. The viewer is compelled, almost forcibly, to focus on details and filigree; context and narrative recede to a dim blur.

Earlier, I mentioned NWR’s penchant for esotericism. If you bear that in mind, so much of Too Old to Die Young’s mannered, baroque presentation starts to make sense. It’s ritualistic, literally; he stages scenes like they’re rituals, the kind that early 20th-century weirdos like adherents of Thelema or the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn might have done. Or, indeed, present-day weirdos like the British monarchy. (Check out the way the knighthood ceremony is framed and edited in the linked video. Throw in some high-contrast lighting, some electronic music, and a couple of people getting shot in the head, and that’s basically any Too Old to Die Young scene.)

Nothing about this series is remotely naturalistic; that’s not the point. In fact, it falls short to say that it’s “not the point”: it’s the opposite of the point. The rigid body-language; the frozen facial expressions; the monosyllabic dialogue; they’re not meant to be evocative. On the contrary: they’re invocative.

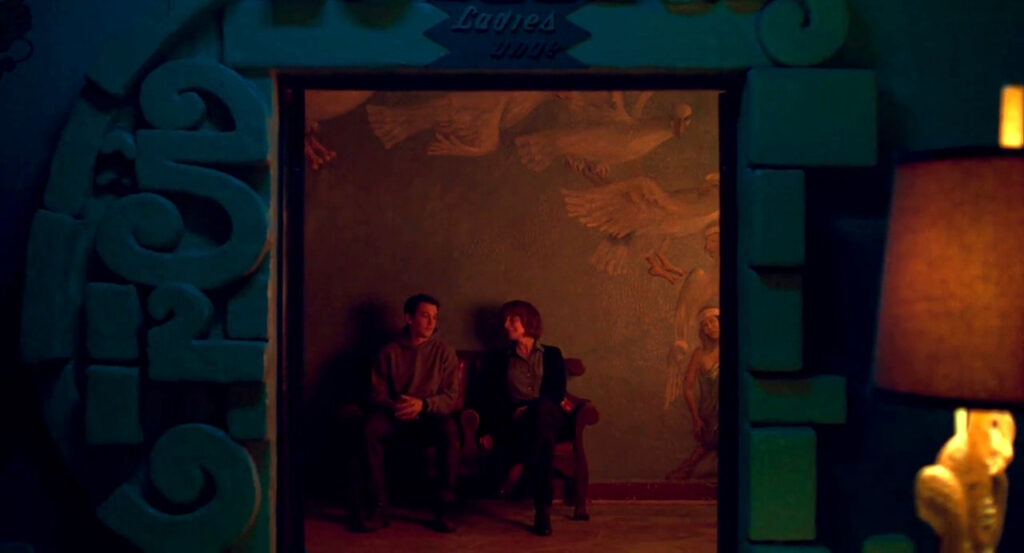

Quite a lot of scenes in Too Old to Die Young explicitly depict ceremonies, of one kind or another; initiations, or hazings, or executions. There’s Jesus’s wordless, shirtless conference with his cousin in The Lovers, where Miguel baptismally rubs fistfuls of cocaine into Jesus’s bare skin. There’s our introduction to Diana in Episode 3 (The Hermit), which finds her accepting a talisman from her clients – a married couple, sitting cross-legged beneath a brass, wire-frame pyramid – in exchange for Viggo killing their son’s rapist. There’s the bizarre parody of a Passion Play that opens Episode 8 (The Hanged Man), where Martin’s Lieutenant (Hart Bochner) absolves him of his decision to quit the police force. (The Lieutenant emerges into the scene with his arms held in a cruciform pose by a mop; a subordinate wearing a legionnaire’s helmet mimes sticking him with a spear on the end of an American flag, then barrels away, chanting “Fake news! Fake news! Fake news!” The scenes in the police precinct are among the few where the show leverages surrealism for comedy, rather than portent.)

Quite a lot of scenes in Too Old to Die Young explicitly depict ceremonies, of one kind or another; initiations, or hazings, or executions.

What is the function of ceremony, anyway? (In art, or in life?) Why do we dedicate time and energy to the rigmarole of getting dressed up and following the elaborate, preordained steps involved in weddings, or funerals, or military parades, or ritual Satanic sacrifices?

My back-of-a-napkin answer would be: because they connect us to a power greater than ourselves. The participants in a ceremony relinquish their personal agency in exchange for being involved in an institution that transcends any one human life. Be it the sanctity of marriage, or the authority of the Crown, or the fervour of MAGA, or the providence of God, or of Baphomet; we are harnessed to some larger thing; some inevitable, irrevocable process.

In the course of thirteen hours of Too Old to Die Young, the impression of ceremony becomes overwhelming. All of its disparate plotlines feel like they orbit around the periphery of some vast, nameless dread, tracing its event horizon. A singularity that can’t be directly observed, but which its players inexorably spiral towards, down and down and down.

The most elaborate, most extended ceremony in Too Old to Die Young takes place in Episode 8, The Hanged Man. Jesus and Yaritza, having taken up residence in Magdalena’s old house in LA, begin their campaign of reprisals, and take Damian prisoner after cutting off his hands. In exchange for a relatively quick and painless death at Yaritza’s hand, Damian sells out Martin; he was the one truly responsible for Magdalena’s slaying.

Jesus’s men track down Martin and Janey where they’re having a peaceful stroll on the beach. They shoot Janey in the head, and drag Martin back to a barn on a remote ranch, where they suspend him by his wrists. Jesus tells Martin, in no uncertain terms, that he will be flogged for three days before being allowed to die.

With two episodes of the series left to go, the reasonable TV watcher might expect some plot complication or intercession on Martin’s behalf; that he might escape, in order for his conflict with Jesus to arrive at some kind of dramatically satisfying crescendo.

Nope. Jesus does precisely as he promises; with the occasional break for increasingly kinky and Oedipal sex with Yaritza, he spends three days lashing Martin with a bullwhip before summarily decapitating him.

Martin Jones’s whole involvement in the plot of Too Old to Die Young ends up being one massive red herring. He has glimpses of a character arc and flecks of dramatic irony in the first seven episodes; the wrongness of his relationship with Janey is held in tension with him discovering his calling as a vigilante paedophile hunter. The show glances up against the idea that he hates himself; that by teaming up with Viggo and Diana, he seeks expiation for his own attraction to young flesh. (He murders Theo in Episode 7 (The Magician) after Janey’s 18th birthday party, when Theo makes lewd comments about his own daughter.)

Martin Jones’s whole involvement in the plot of Too Old to Die Young ends up being one massive red herring.

Just as it looked like he was reaching some kind of self-actualisation by leaving the police force, though: blam. No catharsis. No redemption.

“Too Old to Die Young” is an interesting title for the series to have, and one that the series is clearly proud of. There’s no introductory credit sequence, but each episode begins with those five words superimposed across the screen, one by one, in big, pastel-coloured capitals that a graphic designer somewhere is extremely proud of.

At first glance, it doesn’t bear any obvious reference to the show’s content. When I think of the phrase “die young,” my mind immediately leaps to, e.g., the members of the 27 Club: your Jimi Hendrixes; your Kurt Cobains; your Amy Winehouses; those stars who burned too fast and too bright. None of the cast of Too Old to Die Young are living the kind of fast-paced life of excess and hedonism that some might see as aspirational, that puts you in the ground before your youth and beauty have a chance to dwindle.

But then, there’s the scene in The Hermit when Martin introduces himself to Viggo, over roadside diner coffee. Viggo asks him how old he is, and after a pause (of course), Martin sullenly answers: “Thirty.”

Viggo seems impressed. “Thirty. And already working homicide?”

“I’m just on loan-out from the station.”

“Either way, good for you.”

The viewer, by this point, is keyed-in to the irony here. For Viggo, an old veteran for whom mortality is a very urgent concern, Martin’s future is all in front of him. (Miles Teller would actually have been 30 when this scene was shot, or very close to it; John Hawkes would have been 58.) For Martin, his relationship with Janey burning a hole in his conscience, it must have been agonising to say that number. If you’ve recently experienced a two-digit birthday, you can relate, even if you’re not fucking a teenager on the down-low; that feeling of “oh God, I can never again identify myself by a number that starts with a 1, or a 2.” It feels like a crypt door slamming shut.

There’s no way to phrase this that doesn’t make it uncomfortable: age of consent is a recurring theme throughout Nicolas Winding Refn’s body of work, particularly in the back half of his career. In Drive (by some margin his warmest and most humane film), Standard Gabriel (Oscar Isaac) reminisces about the way he met his wife, Irene (Carey Mulligan):

STANDARD: “We were at a party, and she was nineteen years old.”

IRENE: “Seventeen.”

STANDARD: “You weren’t seventeen!”

IRENE: “I was.”

STANDARD: “Wow. So it was illegal?”

(BOTH CHUCKLE)

In Only God Forgives the entire plot is set in motion because Billy (Tom Burke), quote, “wants to fuck a 14-year-old” in a Thai brothel, and precipitates a cycle of retribution when he tries to take one by force.

And then there’s The Neon Demon, which… hoo boy. 16-year-old Jesse (Elle Fanning) moves out to LA to pursue a modelling career, and lies about her age to get signed with Roberta Hoffman’s (Christina Hendricks) agency. Roberta encourages her to say she’s 19; 18 would be too obvious. Fanning, in reality, would have turned 17 while The Neon Demon’s principal photography was ongoing. There are several sequences in the finished movie that deliberately skirt the line between “this is a thought-provoking satire of the fashion industry” and “FBI!! OPEN UP!!!”

I want to be absolutely, 100-percent crystal-clear on this point: I do not believe that Nicolas Winding Refn condones paedophilia, or that his movies act to launder paedophilia as something acceptable. (By most accounts, away from the camera, he’s kind of a boring, conventional family-guy).

I do think that he’s an edgelord, and that he uses the spectre of paedophilia to wedge open his audience’s fear of aging.

Even as early as 1996, there’s Pusher, which finds Frank (Kim Bodnia) showing up at his mother’s house to beg her for money to pay off the creditors coming to kill him. It’s easily the best, most poignant scene in that movie; this is clearly the first time that Frank’s seen his mother in a while, and she does her best to make him welcome. That her son only needs her to help him clear his debts clearly breaks her heart, and the fact that he clears out her savings to finance his own bad decisions offends our moral sensibilities.

Casting Kim Bodnia as Frank in Pusher was a stroke of nascent genius. NWR was 26 when Pusher came out. Bodnia was 30, but looked older; with his receding hairline and his beer-gut, he’d easily have passed for 34 or 35. Visibly too old to be carrying on with the lowlifes he hangs out with until the wee hours of the morning; visibly too old to die young.

(It’s not lost on me that, when Jang Go Star was going bankrupt, Winding Refn leant on his parents to stay afloat.)

Throughout NWR’s filmography, there’s this persistent theme of characters who don’t want to grow up. Frank in Pusher and Tonny in Pusher II, for starters. In Bronson, Michael Peterson returns to his parents’ house after a stint in prison, and when he arrives in his childhood bedroom, plaintively demands of his mother: “Where’s my stuff?” In Only God Forgives, Julian (Ryan Gosling) is so thoroughly dominated by the expectations of his mother (Kristin Scott Thomas) that he hires a prostitute to pretend that he has a girlfriend, and allows himself to get beaten to a pulp to impress her.

Throughout NWR’s filmography, there’s this persistent theme of characters who don’t want to grow up.

It’s easy to feel too old to die young, in the 21st century. It’s easy to feel that certain milestones have passed you by: losing your virginity; buying a house; getting married; having kids; not being addicted to coke; not being in debt to a gangster; not being financially dependent on your parents.

Martin Jones is too old to be dating a high-schooler, but fate kills him, young or not. He only survived the first ten minutes of the show by accident, anyway; Larry caught a bullet because Jesus made a mistake. For the entire time we know Martin throughout the series’ first eight episodes, he exists in a sort of ontological limbo; granted a few months’ leeway by capricious chance, living on borrowed time before inevitability catches up to him.

Too Old to Die Young, for as much as it’s a singular object, is nevertheless in dialogue with other prestige TV shows. David Lynch’s Twin Peaks is the big, obvious one, the progenitor of surreal, avant-garde American television. (Twin Peaks: The Return was airing in 2017, just as Too Old to Die Young was gearing up for production. Critic Matt Lynch described Too Old to Die Young as “the Goofus to Twin Peaks’ Gallant,” which I wanted to quote because it’s just a terrific turn of phrase.)

Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul can’t have been far from NWR’s mind either, with their oblique scene setups, their panoramic shots of the Mojave desert, and their focus on organised crime transgressing the border between Mexico and the USA. (Episode 5 (The Fool) temporarily relocates the action from LA to Albuquerque, and I don’t imagine that specific choice of city was a coincidence.)

But, in the age of prestige, big-budget TV, Too Old to Die Young’s closest relative is probably Season 1 of HBO’s True Detective. Not unlike Too Old to Die Young, when it debuted in 2014 True Detective was an auteur-driven project to an extent that was rare for television. It was the passion project of novelist and screenwriter Nic Pizzolatto, who single-handedly penned the scripts for all eight episodes. (Notably, there was also just one director for the whole season: Cary Joji Fukunaga. In contrast to NWR, when CJF was asked to direct a James Bond movie, he said “yes.”)

…in the age of prestige, big-budget TV, Too Old to Die Young’s closest relative is probably Season 1 of HBO’s True Detective.

There are a lot of parallels to be drawn between Too Old to Die Young and True Detective S1. Both start out with the veneer of being hard-boiled police procedurals before shedding their skin, emerging as something much darker and stranger and more surreal. Both are cosmic horror stories, wearing the prosaic trappings of crime fiction like drag. Both feature ambiguous supernatural elements that can maybe be dismissed as hallucinations if you squint. In True Detective, it’s the repeated invocation of “Carcosa” and “The Yellow King,” derived from Robert W. Chambers; in Too Old to Die Young, it’s Diana’s visions of silver-eyed extraterrestrials, showing her an impending apocalypse.

Both shows are legendarily pretentious, although they diverge in the specific nature of their pretensions: Too Old to Die Young’s pretensions are visual, whereas True Detective’s are literary. Pizzolatto loads his characters up with erudite, philosophical soliloquies about the provenance of human consciousness and the impetus towards suicide. (Much of the dialogue would register as ridiculous, if not for the career-best performance from Matthew McConnaughey as Detective Rust Cohle.)

I love True Detective S1: if it was the subject of today’s review, I would probably award it an 8-out-of-8, Tour de Good certification. But there’s one part of that legendary eight-episode run that never quite sat right with me, which is the uncharacteristically pat, sentimental epilogue. A convalescent Rust reconciles with Marty Hart (Woody Harrelson) – his erstwhile police partner and the man he cuckolded – and they share a kind of thematic debriefing about the preceding events of the series.

Rust, having survived being stabbed in the gut, looks up at the night sky outside the hospital and reflects upon his childhood in Alaska, contemplating the stars, making up stories about them in his head. “I tell you, Marty,” he says, “I’ve been up in that room, looking out those windows every night here, just thinking. It’s just one story. The oldest. Light versus dark.”

“Well,” Marty replies (who’s always been more literal-minded than Rust), “I know we ain’t in Alaska, but it appears to me that the dark has a lot more territory.”

“You’re looking at it wrong,” Rust rebuts, in True Detective S1’s last line of dialogue, and its final, summative statement. “At the sky. Once there was only dark. If you ask me, the light’s winning.”

I think I get what McConnaughey and Pizzolatto were driving at, poetically speaking – the long arc of history bends towards justice, and whatnot – but as someone with an amateur interest in cosmology, it’s always frustrated me how busted Rust’s metaphor is, here. He’s kind of got it exactly backwards. According to any modern study of the night sky, the universe was an infinitely hot, infinitely dense, infinitely bright point of light 13.8 billion years ago. Astrally speaking, the passage of time is marked by the world growing colder and more diffuse, as the Second Law of Thermodynamics charts its course. In Rust’s own parlance: once upon a time there was only light, but the dark is steadily winning.

In Too Old to Die Young’s cosmology, time is not a flat circle. It’s more like a drainpipe, or a sphincter. Martin and Viggo’s macho, Rambo-esque war against the iniquities of their day is futile; a coping strategy for the inexorability of entropy. Society is fraying at the seams; cities being reclaimed by the desert. Threads of carcinogenic silk are weaving through the hollows of Viggo’s lungs, while his mother’s brain eats itself alive. Sexual conquests that would have been lionised for Martin in high school become wrong and repulsive by dint of the passage of time.

In Too Old to Die Young’s cosmology, time is not a flat circle. It’s more like a drainpipe, or a sphincter.

But, hey: if they can blow up some child molesters in the process, maybe they can make themselves feel better?

There’s no moment at the end of Too Old to Die Young that neatly ties up its storylines and character arcs in a writerly ribbon. You who enjoy things like “plot resolution” will be badly disappointed. The beginning of Episode 9 (The Empress) focuses heavily on Diana, and her interactions with “The Entities,” as she names them. She’s being sent extradimensional visions of blood, and fire, and death, and apocalypse, and at the centre of it all, there’s a woman. (We’re given to understand, of course, that the woman she sees is Yaritza).

In an address to his lieutenants, Jesus pledges to turn America into an amusement park of torture and rape and sadism, like a pitless new Caligula.

With Martin dead, and his mother dead, Viggo marches into a trailer park on the edge of the desert, which Diana assures him is swarming with perverts. His bolt-action rifle rampage is the most aestheticised and perversely beautiful moment of the entire series; a montage of destruction that completely discards spatial continuity, heads being blown off and US flags being spattered with gore and shacks erupting in bright orange fireballs, all in hyper-slow-motion that evokes footage from A-bomb tests, scored by Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture. The fragmentation of visual logic expresses the concomitant breakdown of order and morality that Too Old to Die Young foresees.

That’s not the real climax of the show, though. That comes in Episode 10 (The World), maybe one of the most wilfully confounding television finales this side of Neon Genesis Evangelion’s original run. Even the episode description in the Amazon Prime app is cryptic, reading simply: “The High Priestess of Death reigns supreme.”

It’s only half an hour long – the shortest episode of the series by a wide margin – and what it elides speaks as loudly as what it includes. Neither Viggo nor Jesus even appear onscreen. The terminally ill Viggo is still alive, as best we’re aware, by the time the final credits roll. Yaritza’s dual identity remains in place and undiscovered by her husband. Diana’s prophesied meeting with The High Priestess of Death never transpires on camera. Any plot point involving Martin, Janey, Theo, or Damian is entirely forgotten, like relics buried beneath shifting desert sands. It’s as though they never existed at all.

Too Old to Die Young performatively ignores all of the sources of narrative tension and drama introduced while it was still pretending to be a crime thriller. I can’t imagine what kind of viewer would have stayed with the series for this long if they were invested in it as a story, as opposed to an exercise in form and style. If such a viewer exists, though, The World beats the point into their head with a sledgehammer: this show was always meant to be understood poetically, not literally.

In place of plot resolution, The World instead begins with… a three-minute shot of Diana kneeling on her bed in a silk gown, masturbating while wearing a VR headset. She takes a shower and shaves her legs while the iconic title cards roll; calls in sick to work, while dangling her legs in her pool; watches a public-access TV show about UFOs; dances to Goldfrapp’s “Ooh La La” in her capacious living room. (Is this how victims’ advocates in California’s penal system live? Damn, I’m in the wrong line of work.)

…this show was always meant to be understood poetically, not literally.

Finally, eleven-and-a-half minutes into this thirty-minute finale, we reach the real crescendo of Too Old to Die Young: a shot of Jena Malone, sitting in an armchair, talking towards the camera.

The jaw-dropping monologue that Diana delivers really deserves to be transcribed in its entirety (and bear in mind: this came out in 2019):

“Soon, violence will become erotic, torture euphoric, as the masses hail public executions, propelled by the wrath of fascism. Concentration camps will be rebuilt. Ignorance will be exalted, and there will be race wars, for hate will be rewarded, and seen as truthful, and beautiful. Faith will be reduced to venomous platitudes; a morphine infested enslavement of thought. Perversity will be dignified. Incest, molestation and paedophilia will all be praised. Rape will be rewarded. The few will have everything, and most will have nothing, for not all men are created equal. Narcissism will no longer be suppressed, but worshipped as a virtue. Indulging one’s impulses will become instinctual. Our identities will be defined by the pain we cause. Pure, unadulterated nihilism will be the only solution in the face of glorious Death.”

(Here, Diana’s breath hitches a little, and she pauses for a few seconds before continuing.)

“In time, we will have our own religion. Our own dynasty. And with it, we will wake the true fury of the world. And as man implodes in a wash of blood and silence, a new mutation will emerge.”

(Diana pauses again, and blinks for the first time in three-and-a-half uninterrupted minutes. A single tear runs down her cheek.)

“And on that day, I will declare the dawn of innocence.”

Jena Malone recites this speech in a low, slow, steady voice; ASMR-like, almost a whisper. She’s not speaking to anyone in particular. Diegetically, there’s no-one else in the room with her. She’s not addressing the camera; her eyes are fixed somewhere above and to the left of the lens, seeing something only she can see.

As with every other scene in Too Old to Die Young, the unyieldingly static shot composition forces us to contemplate Malone as a compositional element. We’re forced to notice the twin worry-lines in her brow; the anxious flexing of the cords in her neck; her chest rising and falling beneath her pristine white blouse as she takes irregular, shallow breaths. Her affect is this peculiar combination of beatific and horrified; like if Joan of Arc was a Lovecraft protagonist.

And then, there’s the actual content of the speech. In the fiction of the show, we’re given to understand that Diana is reciting a revelation handed down to her by the extraterrestrial entities who have guided her on her journey thus far. But, as cosmic revelations go, it’s surprisingly blunt and literal in its prosody, isn’t it? (And all the more disturbing for it.) “This awful thing, then this awful thing, then this awful thing, etc.” It’s Too Old to Die Young in microcosm; hushed, reverential intonation afforded to a near-arbitrary sequence of profane images.

In 1919, exactly a century before Too Old to Die Young dropped on Amazon Prime, Irish wordsmith and noted Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn member William Butler Yeats composed his most famous poem, “The Second Coming.” With World War 1 not long finished, the Irish War of Independence revving up, and the Spanish Flu dropping Europeans more expediently than four years of mortars and mustard gas, it encapsulates the apocalyptic mood of the era in twenty-two lines of free verse. “The Second Coming” is much more artful in its metre and phrasing than Jena Malone’s monologue, and evokes a more religious mode of terror in its imagery.

Still, there’s a peculiar similitude in their sentiment. “We’re fucked” is the thesis of both texts, and both play out as a series of bone-chilling statements, straining to capture the enormity of just how fucked we are. (I’m particularly struck by the resonance between Yeats’s “The blood-dimmed tide is loosed” and Diana’s “…as man implodes in a wash of blood and silence…”)

Donald Trump is never once named in dialogue in the course of Too Old to Die Young; his image is never seen, and his voice is never heard. And yet, his spectre haunts the series from beginning to end. If one were to collapse all thirteen hours of the series into a single, Shulman-esque image, I have to imagine it would be his beady-eyed, Fanta-orange visage, staring out at the viewer. Too Old to Die Young was filmed between November 2017 and August 2018, in the back half of Trump’s first term. Back then, his regime, though monstrous, still had something pathetic and buffoonish about it. Alec Baldwin – William’s brother – could still elicit laughs from his broad impersonation on Saturday Night Live.

Jump forward to 2025, and it’s not funny anymore. Diana’s prophecy feels far more vivid; higher resolution.

In a world where Venezuelan expatriates are being requisitioned to concentration camps in El Salvador without trial; a world where the head of the newly initiated Department of Government Efficiency (kill me) performs a Nazi salute in celebration of the President’s second term; a world where seemingly every influential figure you can name crops up in the flight logs of a conveniently hanged sex trafficker; a world where multimillionaire pastor Joel Webbon preaches how “Christians must recover the lost virtue of Hatred…”

How are we to conclude that the world hasn’t been turned upside-down? In what version of events is there a way out of this, a sluice gate through which we might escape this downfall? As I write this, I’m a few weeks away from my 35th birthday – I’m too old to die young, myself – and for me and a lot of millennials my age, we’re confronted with a time when the institutions we thought were secure and sacrosanct are crumbling beneath our feet; when the virtues we believed inviolable have been inverted.

The centre cannot hold. The falcon cannot hear the falconer.

In the course of writing this review, I’ve debated whether Too Old to Die Young should be called a “nihilistic” show, or merely a “fatalistic” one. (Yes, the distinction matters.) I think the latter is probably more accurate. (Genuinely nihilistic art is rare, if not outright paradoxical; if you care enough to get up in the morning and shoot, then surely you must attach enough meaning to something that it’s worth the effort of communicating it?)

In the course of writing this review, I’ve debated whether Too Old to Die Young should be called a “nihilistic” show, or merely a “fatalistic” one.

I don’t think Too Old to Die Young discounts the possibility of human beings finding meaning in their endeavours or their relationships. It does, however, discount the possibility of any individual’s actions making a difference to their macroscopic circumstances. Prestige TV in the streaming era loves its antiheroes, but Too Old to Die Young doesn’t even exist on the hero/antihero continuum. It regards even the idea of a protagonist with savage disdain and mockery. In hindsight, the idea that Martin Jones was ever equipped to be the protagonist of anything is laughable.

If hope exists in Too Old to Die Young’s setting, it lives in Yaritza, who gets the final word before the credits roll. Much like Martin and Viggo, she’s a vigilante avenger, disrupting the channels of human trafficking by brutally killing those who participate in it, with guns and knives. Martin and Viggo’s efforts are framed as futile and pitiable; self-deluding men who think they can turn back the tide. Yaritza, however, has an escape clause that they don’t: she’s not human. It’s not clear what she is (remember: poetic, not literal), but she’s equipped with an inviolable purpose and intent that transcends the limits of fallible humans. “An unadulterated extermination machine,” as she describes herself, “eliminating all evil from the universe.”

(Of note: the next series that NWR would make was the Danish-language Copenhagen Cowboy, released on Netflix in 2023, which features as its protagonist another mysterious, near-mute young woman of seemingly otherworldly origin, who comes to the rescue of people in need with her preternatural combat prowess. Clearly there’s an archetype that NWR enjoys, here. I don’t like Copenhagen Cowboy nearly as much as Too Old to Die Young, in large part because it makes its supernatural elements much more textual and unambiguous. It’s far more of a straightforward superhero story.)

The final scene in the show finds Yaritza confronting a unit of Jesus’s men where they’re hanging out in a church, refitted as a bar where a group of trafficked women wait upon their pleasure. After messing with their heads for a few minutes, she shoots them all dead in a brief firefight that looks as easy and natural to her as breathing. She strides out the door into the glare of the desert sun, leaving the bodies where they lie, a cleansing fire poised to engulf the world. The camera shamelessly objectifies Cristina Rodlo as she goes, with her incredible printed bomber jacket/red-leather trouser combo; her bare midriff; her sashaying, catwalk-ready gait. A sexy beast, her hour come round at last, strutting towards Bethlehem to be born.

The final credits kick in, with a deep cut from Judas Priest’s 1974 debut album closing out this whole, meandering, 13-hour vision quest:

Rocka Rolla woman

for a Rocka Rolla man.

You can take her if you want her,

if you think you can.

So… what are we to take away from all of this, in the final reckoning? Deriving meaning from Too Old to Die Young often feels like trying to catch a greased pig. Themes flit hither and thither, glimpsed out of the corner of your eye and gone by the time you turn your head. It’s an elusive, mercurial experience, and it frequently gives the impression you’re being baited. The moment you think you’ve found something to attach significance to, NWR will shout “psyche!” and open his fist, revealing nothing in his palm.

Is it about the rise of American fascism and MAGA? Is it about coercive sexual power dynamics? Is it about the futility of violence and vigilantism? The pain of aging? The unstoppable arrow of time? The Jungian Collective Unconscious? The impending apocalypse?

Kind of all of the above, and kind of none of them, I guess? Some ineffable feeling, lurking at their common centre of gravity?

It’s probably a mistake to ascribe intent to any meaning you do find in Too Old to Die Young. In a 2013 profile by The Guardian, NWR rather infamously referred to himself as a “pornographer.” The full quote is as follows:

“It’s like pornography. I’m a pornographer. I make films about what arouses me. What I want to see. Very rarely to understand why I want to see it and I’ve learned not to become obsessed with that part of it.”

On more than one occasion, he’s described his approach to his subjects as “fetishistic.” I agree, with the provision that it’s not in the contemporary sense that the word “fetish” is used to mean “weird sex thing.” It can mean that, and sometimes does, but at its root, a “fetish” refers to an inanimate object treated as possessing some kind of indwelling spirit or potency. (Google’s dictionary suggests “talisman” or “totem” as potential synonyms.) To shoot something “fetishistically” is to treat it as having some kind of inherent, a priori significance. Why not linger for minutes at a time on the ornaments on the walls of an Albuquerque dive bar, or a character’s unnamed daughter practicing a figure-skating routine, or the eye/tree/skull print on the back of Yaritza’s bomber jacket? Why does there have to be a reason for these images, except that they call to the person composing them, the way that, say, a card calls to you when you draw it from a deck?

In The Hermit, when the Lieutenant is mentoring Martin as a newly-promoted detective, he gives him some sensible and level-headed professional advice about how he might track Viggo down, and then shows him a single, six-sided die he keeps on his person. “To me, it’s a philosophy,” the Lieutenant says. “I had the highest clearance rate in the squad because of this. You can follow evidence and build theories all day long, and then your perp turns out to be some random stranger. We force order onto life, so we believe our choices matter, but it’s really all random, isn’t it? So, you have to embrace that.”

This speech is where Too Old to Die Young tips its hand. It lives in that grey area between intentionality and chance; between determinism and free will. It isn’t just a core theme for the show, it’s also its artistic strategy. It’s the product of a cluster of creative impulses being pursued compulsively; instinctively; unconsciously; libidinally.

We return again to that tarot motif. Any one card by itself isn’t special, but any 10 cards drawn from a shuffled deck of 78 will produce one of 4.5 quintillion possible combinations. You could draw 10 cards once every second, and the sun would burn itself out long before the same combination of cards appeared in the same order twice. Its significance is generative. Invocative, you might say.

I don’t think that any of the elements in Too Old to Die Young’s 10 episodes are all that special by themselves. Not the themes. Not the performances. Not the dialogue. Not even the visuals or the music. But collapse all those parts together, Shulman-like, and you get something that’s never happened before. Numinous and potent and irrational, untouchable by sober-minded analysis.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say there will never be another TV show like Too Old to Die Young; in the fullness of time, who knows what might happen? Every so often, the planets align, and a visionary weirdo like Nicolas Winding Refn encounters an opportunity like the late-2010s streaming boom, and runs with it.

…when I watch Too Old to Die Young, I experience a combination of feelings that I don’t get from anything else I’ve ever seen.

I will go so far as to say that, when I watch Too Old to Die Young, I experience a combination of feelings that I don’t get from anything else I’ve ever seen. Awe; dread; befuddlement; dark mirth; those are all there. But, beneath those, a sense of meditative calm. Of fortification against the essential randomness of life. I’ve watched it from beginning to end twice, now, and both times I’ve come away feeling oddly cleansed, like I’ve been scrubbed by a rough-bristled brush.

Do I recommend that anyone else should watch it? I can very easily imagine a viewer who would hate it, and I couldn’t even tell them they’d be wrong to do so. I guess all I can say is that, if anything I’ve described here activates something in you – if it arouses your curiosity – then give Too Old to Die Young a try. (After having seen Drive and Only God Forgives, remember.)

What that means in terms of score, hell if I know, but I’m writing this for a site whose brand is its 1-to-8 metric, and my best numerical approximation of my feelings is…

Is It Good?

Masterpiece: Tour De Good (8/8)

Andrew is a 2012 graduate of the University of Dundee, with an MA in English and Politics. He spent a lot of time at Uni watching decadently nerdy movies with his pals, and decided that would be his identity moving forward. He awards an extra point on The Goods ranking scale to any film featuring robots or martial arts. He also dabbles in writing fiction, which is assuredly lousy with robots and martial arts.