The problem with choosing “intolerance” as a theme for your time-sprawling opus is that it is so shapeless and blunt as to lose all meaning. Literally anything can be described as “intolerance” from a certain perspective: Your coworker stole your sandwich from the fridge? He is intolerant of your right to possess pastrami in communal space.

Thus we get DW Griffith’s “Intolerance” subtitled “Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages,” and, philosophically, it’s a lot of dreck. We’re supposed to believe the Women’s Suffrage movement is a moral evil in line with Pontius Pilate and the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

This gets even hairier when you dig into the film’s origin story. Griffith was in the midst of a huge backlash for his technically majestic but morally wretched Birth of the Nation, an anti-Black, pro-KKK ode. Intolerance came out one year later. Some read it as an apology for his “racism is ok” epic; others read it as an indictment of his critics who decried his “racism is ok” epic — basically the 1910’s version of the “cancel culture is ruining America” argument.

Regardless of the spark that caused him to create Intolerance, it remains one of the grandest and most awe-inspiring films ever made. It tells four stories in parallel, with a fifth, recurring image — Lillian Gish as an ageless, timeless mother, rocking a cradle — which serves as a cue of a transition between stories and/or themes.

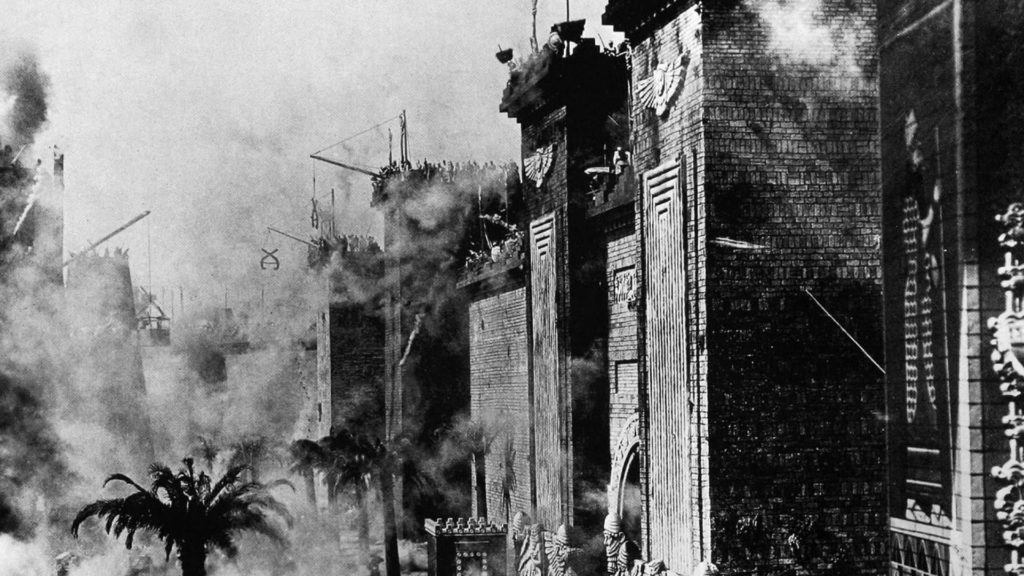

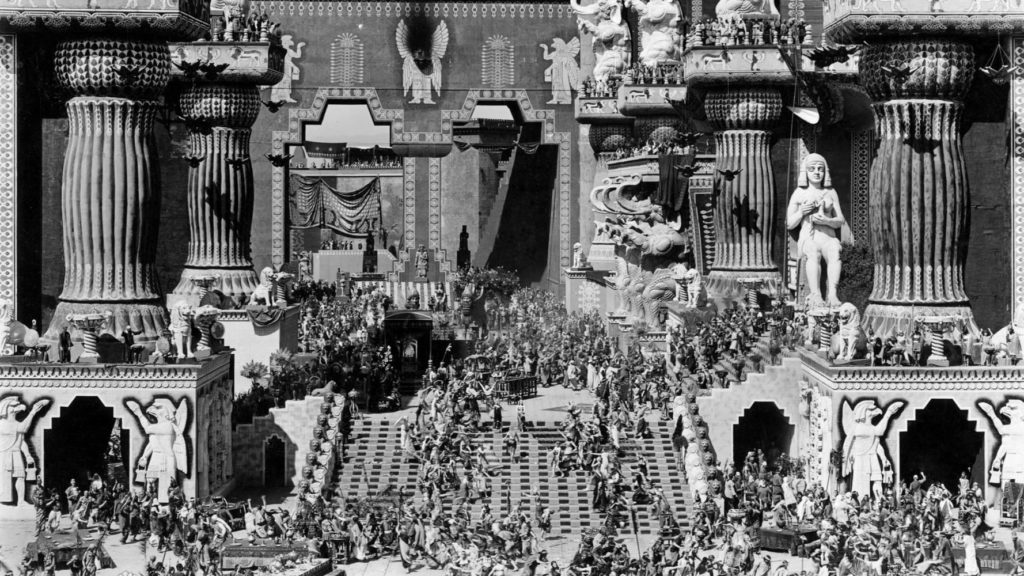

Emboldened by the success of Birth of a Nation, Griffith pulled out all the stops and created a film of unprecedented scope in narrative ambition and sheer spectacle. The story that takes place in ancient Babylon is especially mindboggling. Extras count in the hundreds to thousands; recreated ancient town blocks, city walls, and festivals are a feast for the eyes. Other stories shine, too: the 1500s-era French palace is huge, open, geometric, and extravagant.

Everything I wrote about Griffith’s craft and instincts in my review of Birth of a Nation still holds true here. His ability to compose shots that amplify both epic stories and intimate human emotions is profoundly skilled and affecting. He has an intuitive knack for telling grand stories at a fluid pace so that the sprawling plot rarely drags.

As a director, Griffith has two new filmmaking tricks in his arsenal. The first is the use of intense close-ups to highly evocative effect. This camera placement, paired with precise lighting that contours the face and brightens the eyes, makes for shots of actors’ faces that are expressive and occasionally downright haunting.

The second new trick of Griffith’s is a bit harder to define: When cutting between stories in different time periods, visual elements often mirror or counter the image previously seen. The association or emotional reaction to the relationship between two images emphasizes story or thematic content: For example, a cut from a collapsing siege tower in a Babylonian battle scene to the staircase of an apartment in 20th century America. The similar vertical shapes intuitively project a sense of danger in the latter in an almost subconscious way: If the Babylonia siege tower could lead to death and destruction, surely something dangerous could happen within these apartment walls, right? Sure enough, a mother’s baby is taken from her one scene later.

Both of these cinematic techniques would become crucial tools in European silent art cinema over the next decade.

Griffith keeps his camera still for most of the duration of the film, allowing us to soak in the extravagance of the set and the action. This makes it all the more breathtaking when he finally starts moving the camera in the film’s second half. One swooping shot of an orgiastic Babylonian festival with hundreds of extras literally made me gasp out loud when I saw it: I could feel the swelling frenzy.

For as much as I object to anything else in the movie, the sheer scope of the production design is truly extraordinary. This is, without exaggeration, maybe the greatest specimen of production design in the history of cinema: Palatial city squares, terrific costuming from four different eras, richly decorated interiors, a mix of decadence and stateliness… truly a feast of production design on an almost mythological scope.

The four films spotlighted on the 1001 Movies to See Before You Die list prior to this include plenty examples of competent acting, but never anything scene-stealingly great or memorable (excepting perhaps the seductive Musidora as Irma Vep in The Vampires). But all that changes in Intolerance: we have some truly mesmerizing, emotionally explosive performances. The crown jewel is Mae Marsh as the tragic “Dear One” from the modern storyline: Her wide, expressive face and anxious physical presence is melodramatic mastery. Robert Harron shines as her bum-luck lover, The Boy, who evokes a hapless likeability. Other standouts include Constance Talmadge as the earthly Mountain Woman in Babylon and Miriam Cooper as the jealous, conniving Friendless One from the modern day.

Intolerance is a luscious four-course feast for the eyes and a monumental achievement of filmmaking, but it’s nearly as problematic as it is great. As mentioned, I found the philosophical and didactic core of the film to be bunk, and I was always inclined to make the worst interpretation of any of the movie’s dubious politics given Griffith’s work in Birth of a Nation.

More to the point, the movie loses more than it gains from its ambitious, four-timeline script. It simply lacks focus: The modern story has the most heart and nuance, while Babylon is the show-stopping spectacle. The French Renaissance story is fairly flat in spite of the cool productions, and the segment depicting the Gospels is so minor it could just as well have been cut completely. (There’s an odd inertness to what could have been a thrilling religious biography; it’s a disappointment after some of the historical recreations in Birth of a Nation, like Lincoln’s assassination, were so riveting.)

As a result, despite Griffith’s ability to keep the material moving, Intolerance feels ungainly and bloated. So much exposition is required in sum across four stories that it feels like forever before the good stuff starts happening.

The flip side, of course, is that the last hour is pretty incredible: Four simultaneous climaxes crashing down in fascinating, parallel ways. It’s terrific payoff on the arduous 2.5 hours of setup leading to it.

It adds up to an early canonical masterpiece that is overpowering but overstuffed. It is occasionally transcendentally brilliant, but more often clunky due to its overstretched story.

I’m glad not to see the KKK this time, though.

(I’m attempting to watch 1001 Films to See Before Your Die in chronological order. This is film number 5. I’ve slain the 1910s. Up next is the 1920 German horror film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.)

- Review Series: D.W. Griffith

Is It Good?

Good (5/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.