For lack of a better word, is good

They call it the white whale, the Holy Grail of lost films. The original cut of Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, screened exactly once for a private audience of twelve in January 1924, has become celluloid legend. Film historians have struggled to wrangle the line between fact and hearsay for a century now. The most deranged myth clocks the original edit at 100+ reels, which would be an all-day mega-movie — greed indeed. Historical consensus and Stroheim himself put it at 42 reels (or possibly up to 47), translating to somewhere between 8 and 9.5 hours depending on projection speed. Stroheim later cut it down to 24 reels, reportedly imagining a two-part epic in the Dr. Mabuse mold. But when even that proved too ambitious for studio brass, he reluctantly turned to his friend and fellow director Rex Ingram to pare it down to 18 reels, a version Stroheim considered a compromise but not a violation of his vision. That was the cut he hoped would reach the public.

But the industry giveth and the industry taketh away. Around this time, Metro Pictures folded into a new corporate monolith: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. And with MGM came new executives, including two names that would haunt Stroheim’s career — Irving Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer. Thalberg and Stroheim already had beef dating back to Foolish Wives’ butchering, and Mayer would soon join the fray as Stroheim’s personal nemesis. The pair overrode Stroheim’s vehement protests and hacked Greed down to 10 reels, a little over two hours long. If the 18-reel version made Stroheim queasy, this one left him livid. He called corporate-hired editor Joseph W. Farnham a “hack with nothing on his mind but his hat.”

And so it went: for decades, the ten-reel Greed was the only one anyone could see. Whispers of a longer version occasionally bubbled up — someone claimed to have seen a cut in Prague, or a print supposedly turned up in a film club basement in Boise — but the trail always ended in smoke. MGM denied claims that any extra footage was lying in its vaults. Stroheim, ever the enigma, both encouraged rumors of a surviving 42-reel version (at one point suggesting Josef Stalin owned a copy) and also accused MGM of melting the original negatives for their pennies worth of silver content. Whatever their fate was, the original reels are almost certainly gone.

But while the footage was lost, its absence grew more famous over time thanks to burgeoning interest in film history. Starting in the ’60s and ’70s, scholars pieced together scraps of Greed’s remains — production stills, script drafts, contemporary synopses — and began publishing detailed retrospectives. The most famous effort came in 1972 when Herman G. Weinberg published a book attempting to resurrect the original via stills and script excerpts. In 1999, Turner Entertainment 3took this one step further, combining the ten reels of existing footage with hundreds of stills and new intertitles based on Stroheim’s own outlines. This 4-hour reconstruction aired on Turner Classic Movies. Its blend of stills and moving picture makes it a challenging watching experience, but it’s as close as we’re likely to get to witnessing Stroheim’s vision unfold.

When the film hit theaters in 1924 in its ten-reel format, it landed with a thud. Greed tanked both critically and commercially. Many reviewers at the time mocked the film for the very traits later generations would revere: the grim naturalism, the slow and agonizing descent into poverty, the visual bluntness of characters in emotional and moral freefall. Stroheim’s refusal to beautify his sets or his actors gave the film a bruised, lived-in realism that ran counter to Hollywood’s image as a dream factory. Instead of studio back lots, Stroheim shot on actual San Francisco streets. He hauled cast and crew to Death Valley for the finale. The film’s brutality — emotional, economic, physical — failed to resonate.

I don’t entirely blame audiences; it’s tough watch. When movie lovers discuss Greed, they almost always do so in the context of operatic artistic martyrdom, of restoration detective work, and of an eternal search for a hidden treasure. That myth-making is more interesting than the two hours of existing footage we actually have, which I say as someone who likes the film. Case in point: Jonathan Rosenbaum’s BFI monograph on Greed spends most of its page count on production history and comparative text analysis, rather than on critical evaluation. Granted, his analysis came out pre-Turner cut when its backstory was less accessible, but the emphasis is telling. Even Rosenbaum, who ranks Greed as one of his ten favorite movies ever, knew the real draw was the tragic meta-story.

Greed is a faithful adaptation of Frank Norris’s novel McTeague: A Story of San Francisco, an 1899 piece of realist literature about a slow descent into desperation. Norris’s book tries very hard to be The Great American Novel and succeeds in the sense that it taps into a swath of turn-of-the-century American themes: the corrosive role of money in relationships, the dream and perils of upward mobility, the gender and sexual friction of early feminist awakenings, and the psychic damage of living under industrial capitalism. (The novel also traffics in some late-19th-century anti-Semitism, which Stroheim thankfully filters out.)

(Note: I’m about to discuss the full plot of Greed, including its ending, so if you are averse to spoilers, here’s your exit point.)

The plot, at least in its basic framework, is fairly simple. McTeague (Gibson Gowland), a dim but well-meaning dentist, falls in love with Trina (ZaSu Pitts), a delicate, nervous type who wins a small fortune in the lottery right around the time they get married. Rather than improve their lives, the money quickly becomes a point of tension and obsession. Trina refuses to spend it; McTeague grows embittered. Their relationship curdles, and so does their luck. Their main foil is Marcus (Jean Hersholt), Trina’s former lover and McTeague’s best friend, who resents Trina and McTeague’s sudden wealth. Marcus betrays McTeague over and over. McTeague eventually loses his dental practice and struggles with menial labor. Trina clutches the purse-strings ever-tighter, and McTeague finally snaps, first robbing her and running off, then returning home and murdering her in a violent rage when he’s destitute. The story culminates in one of the bleakest endings of the silent era: With McTeague on the run from the law, Marcus tracks him down in the middle of Death Valley. The pair scuffle one last time. Marcus perishes, but not before cuffing himself to McTeague. The movie wraps with this final image: a long shot of two men bound, one living and one dead, with no water in a sun-cooked wasteland. McTeague waits for death in the heat of the sun that resembles white hellfire as he stares at a pile of the blood-spattered golden coins that brought him to this point.

Most of what was cut by MGM is a novelistic sprawl in the telling. The 42-reel cut reportedly contained a web of side stories from the novel: other San Franciscans, each locked in their own struggles of desire and desperation, mirroring or distorting the central love triangle. These characters and their little rhyming tragedies lent Greed a texture closer to a literary epic than a traditional film narrative. But when MGM slashed the runtime, most of those subplots were removed entirely, leaving just the core plot skeleton: Mac and Trina, love poisoned by money. What we’re left with is a narrower story than Stroheim had in mind, more of a tragic two-hander than a social fresco.

The film is defined by a powerful tension between two competing concepts: heightened melodrama and gritty realism. Each plot point has both an operatic element of fate to it, but also the glum mundanity of everyday poverty. This peculiar split of tones is what makes Stroheim’s sensibility so hard to pin down and discuss concretely. He repeatedly claimed he was a “realist” and not a showman, but his version of realism veered into expressive and showy territory.

The lottery plot, for instance, is realism wrapped in fantasy, or maybe vice versa: Trina’s win brings her no joy or bliss; instead, it amplifies her neuroses rather than liberates her, and McTeague’s affections morph into snarling greed. This suggests a theme of dramatic irony more than realism — each character failing to see that their gifts are holding them hostage, that a modest compromise would likely make both of them happy. In the Turner cut especially, the irony and self-delusion accumulates, with Stroheim building the misguided worldviews of junk hoarders, fortune-tellers, and money-hoarding retirees upon twisted relationships with money.

Visually, Greed is just as strange and two-headed as it is a piece of storytelling. In a visual texture predicting the neorealism that would emerge in Europe a couple of decades later, Stroheim clung to the ordinary ugliness of real locations and plain costumes — cracked walls and stained garment on display. But he also dabbled in radical formal choices that feel more at home in expressionism or even experimental cinema. Take the gold tinting: Stroheim and his team eschewed most hand-coloring except for the gold objects in the film, a visual obsession so specific it borders on fetish, echoing the psychology of the characters.

Meanwhile, the Death Valley shoot of the finale wasn’t just method — it was madness in the name of capturing authentic agony. Weeks of filming under brutal conditions led to cast and crew collapsing from heat exhaustion. A cook on staff died. Stroheim insisted Greed must feel lived, sweated, and suffered, but the cruelty it puts Mac and Marcus through verges on hyper-real and elevated, like this is the afterlife rather than Earth.

From a camera placement perspective, Stroheim embraced realism only as far as his storytelling instincts allowed: He favored proscenium-like framing with minimal use of reverse shots. Thus, the audience has a static, theatrical view of the drama that avoids modern coverage or sense of space. This adds a sense of entrapment that mirrors the characters’ own doom spirals.

The performances continue that theme of walking a tightrope between theatricality and realism. Gowland, has a permanently furrowed brow and massive, hound-dog eyes. He plays McTeague as a doofus whose heart poisons to villainy: earnest, wounded, increasingly dangerous. It’s a self-deprecating performance in that Gowland humiliates himself and subsumes himself in the character’s painful spiral (long before we knew what “method acting” was). Pitts, meanwhile, transforms Trina from a dainty and restrained wallflower in the opening stretches into a money-loving caricature verging on grotesque and maudlin. Her descent is exaggerated, manic, and astonishing. By the final act she’s writhing in bed near-nude, her money apparently gratifying her the way her absent husband no longer does.

So does Greed live up to the myth? Not exactly. But that’s inevitable. The film’s reputation was built on absence: that which we don’t have, that which we’ll never see. It’s a half-decomposed cinematic corpse. The film’s title helps with its stature — short, grand, Biblical — and its behind-the-scenes narrative is irresistible Hollywood lore.

And yet, in any extant version, the film retains brute force and arch drama. The four-hour Turner restoration is an academic exercise, but it is very revealing. The MGM cut is cleaner as a viewing experience, but hollowed out. I’m honestly not sure what the ideal edit would be as a viewer rather than a film historian; I can’t say I would enjoy sitting through an 8-hour epic: As much as the original cut is mythologized, we shouldn’t ignore the feedback among some who saw it that insists it was too damn much for one film, and films edited by editors are usually better than films edited by their directors (see: about 90% of “director’s cuts” being worse than their originals).

The Turner restoration does reveal a few segments that would have improved the MGM cut: stills from a fist-fight between Marcus and Mac indicate a boldly-shot turning point in the story, while the discovery of Trina’s body was censored but depicted a brutal and bloody image for the 1920s. It would have packed a major punch and echoed moments earlier in the film.

So I guess my dream version of Greed is something like a slightly expanded and cleaned up version of the MGM cut. Or if we’re in fantasy land, Stroheim can reincarnate himself in the 1970s and make Greed as an experimental formalist film, or maybe in the 2020s and turn it into an Apple+ TV miniseries.

Here are a few shots of the best material for which we have stills but no film that I’d like to have seen in its complete form:

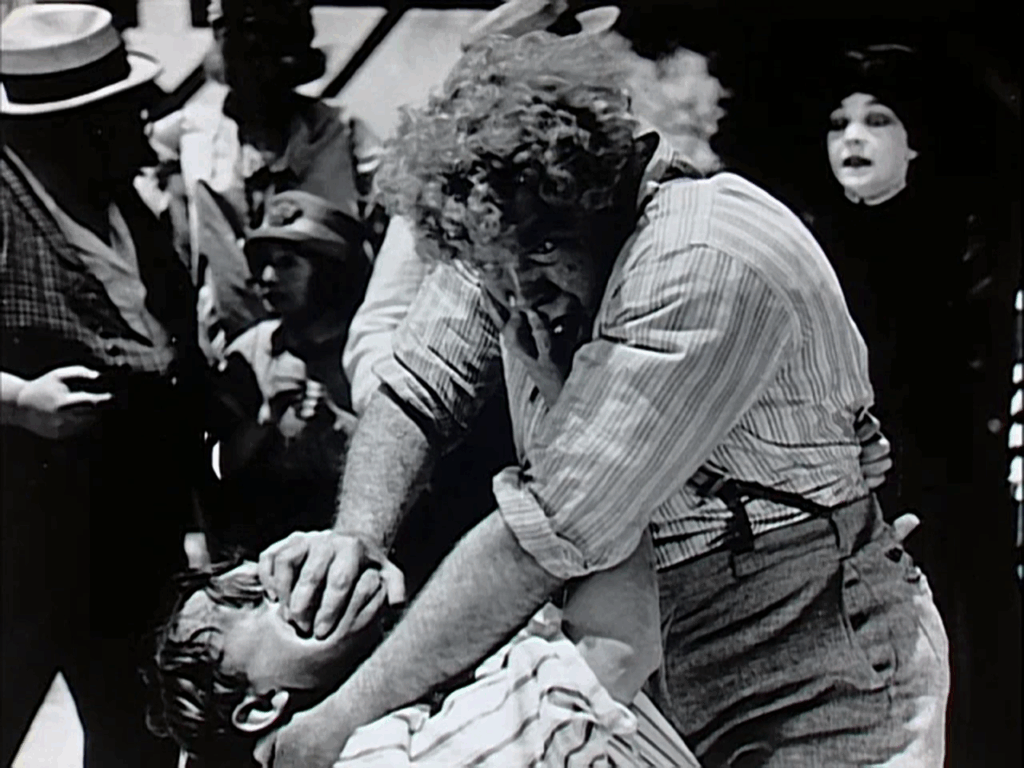

Fight between Marcus and Mac

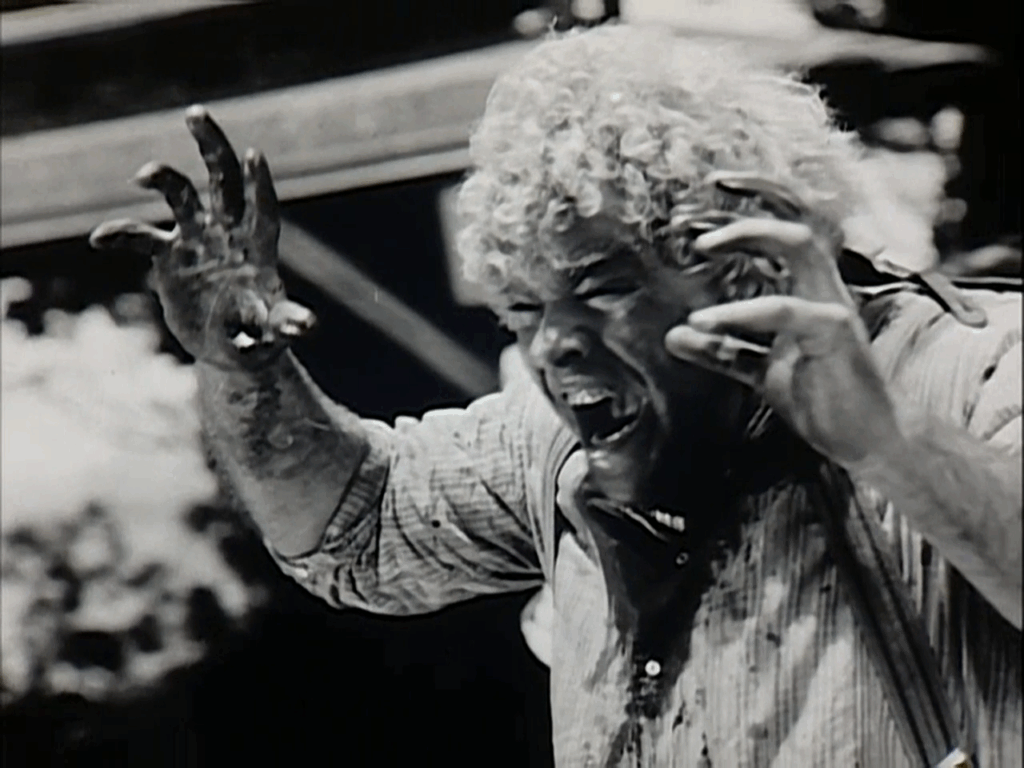

Trina’s death discovered:

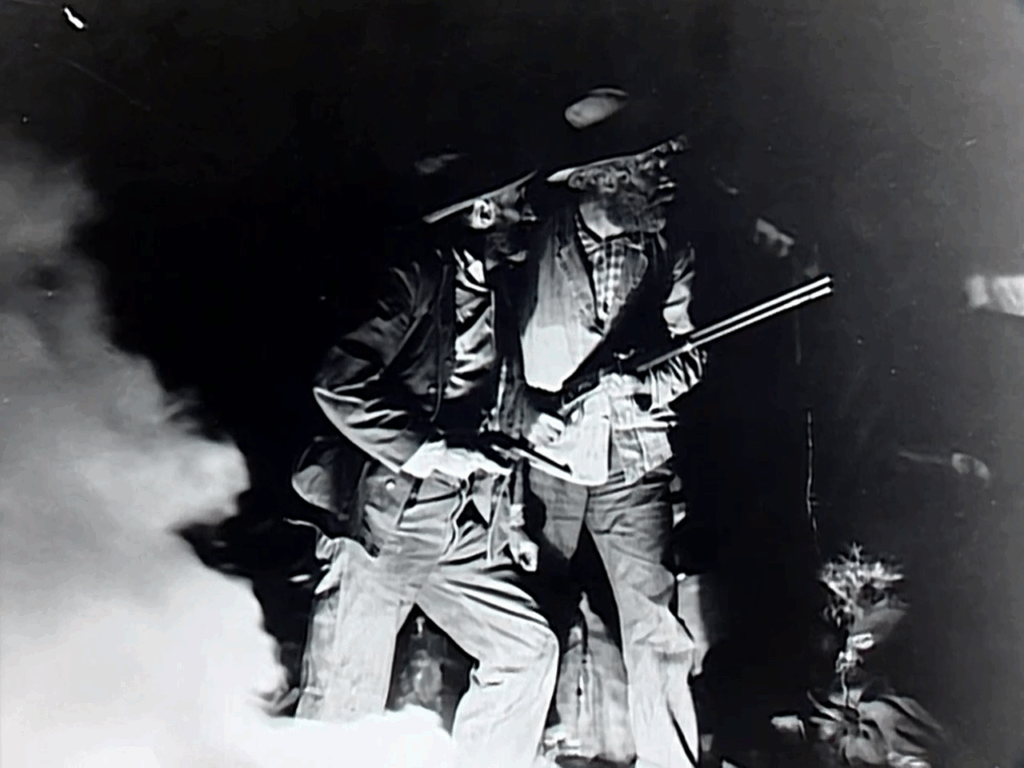

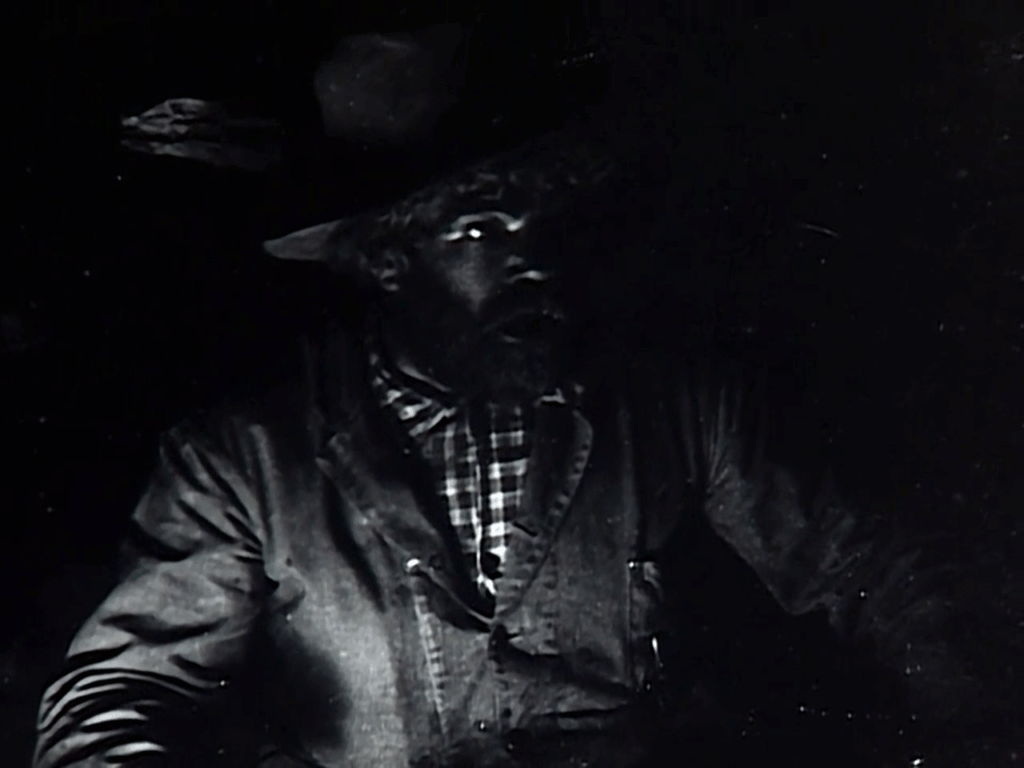

Mac’s expressionistic Death Valley night terror:

Alas, there is no one right answer for a “best cut” of Greed. No matter how you watch, you can never escape the sense that this film is broken. Foolish Wives might be Stroheim’s more coherent and watchable achievement today, but Greed is the stuff that dreams are made of.

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “Greed (1924)”

Why, he’s got a giant bag just full of water right there.

Does sound pretty cool, maybe I oughtta just try the MGM cut. Give Thalberg this: it is undoubtedly true that I would never a workday-long moralizing silent movie about wretches in the 1890s, and I probably wouldn’t watch a four hour one either, at least without loving the bejeezes out of a two hour cut-down of it. Bummer that the other cuts don’t fully exist for the fans and for posterity though.

“I thought they smelled bad on the outside!”

I actually agree with you that I don’t think a monolith 8-hour cut would result in a better film. I had meant to add to this review what material I’d really like to see added back to the MGM cut in lieu of some lazy intertitles, so I just went and revised the ending of this review and added some stills of the missing material since I was discussing it anyways.

Maybe only The Magnificent Ambersons equals Greed for the legend of what was lost to history.

Maybe it’s just the dying relevance of silent film in general but I hear people talk about Ambersons more than Greed these days. It’s probably the talkie white whale, at least.

When the 1917 Cleopatra clip emerged two years ago, I read a couple of takes that it was in fact our greatest lost film. (Though in that case, it’s completely lost rather than partially lost, which is maybe a distinction.)