The film serial was an early cinema format that is, in some ways, more familiar today than ever, though through a different mechanism: Long, continuous stories broken down into episodes of varying length? The episodes can be watched individually or binged as a continuous whole? That, in a nutshell, is the format of streaming TV shows in 2021.

The Vampires — also known as Les Vampires, also known as The Arch Criminals of Paris — is a silent French crime serial from 1915. It is a lot more palatable as a 10-episode miniseries than as a 7-hour film — but is a compelling spectacle no matter how you watch it. Created by Louis Feuillade, known today as the master of the 1910s French cinema and the figurehead of the serial format, The Vampires was conceived and marketed as pulpy, trashy fun, as opposed to the “artistic films” of the day, e.g. DW Griffith’s films. Critics panned The Vampires as brainrot at the time. But it’s clear that this has aged better than the supposed serious cinema of the time like The Birth of a Nation in many ways, even aside from the abhorrent racial content of the latter.

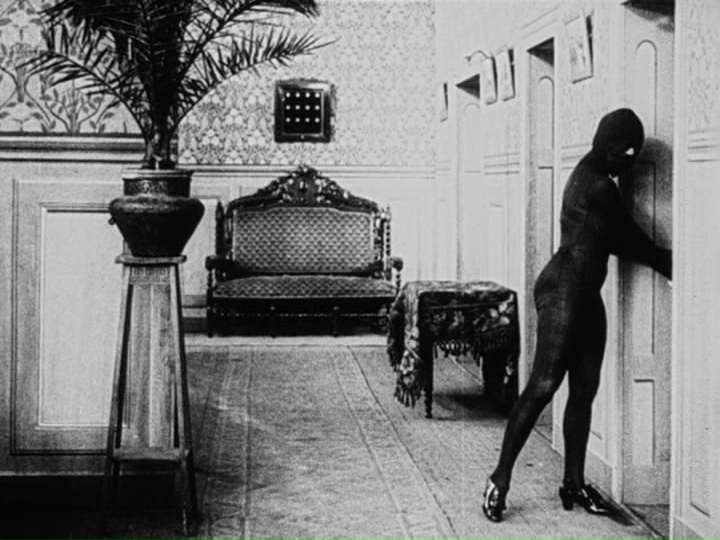

The story follows an investigative reporter and his bumbling sidekick who are tracing down the criminal conspiracies of a gang known as the Vampires (sadly non-supernatural; just a cool name). The Vampires are led by various disposable criminal overlords. Their real star is Irma Vep (played by Musidora), the dangerous and sexy anti-heroine with a signature outfit of black tights.

Crime stories have a way of mirroring cultural values and concerns of the day. On that front, The Vampires is a tour de force: The bourgeois is frequently infiltrated by the Vampires, and nobody thinks much of it. To be rich in that time and place was, definitionally, to be in league with corruption and criminal enterprise. Many up-and-up characters have double identities or dark secrets in the same way that a populace was weighed down by trauma of a continent-spanning war. It adds up to a portrait of a pessimistic culture dominated by an amoral upper class — something that’s certainly still evocative in 2021.

The story is driven by crackerjack set pieces built around phenomenal indoor sets: Secret compartments, trap doors, hidden peepholes, and other insidious physical spaces are used frequently and creatively. There are a few outdoor chase scenes, but the fun is typically centered around stealth and double-crosses.

The plot itself is very twisty and expansive, with an ever-growing cast. New gangs enter the picture; familiar faces pop up unexpectedly. By the third episode, I needed a crib sheet to keep up with the characters and their various relationships (Wikipedia has a thorough plot summary, and this one is very good too — I confess I had it open on my phone most of the time while watching).

Despite its low-art aspirations, there’s something very postmodern about The Vampires. Feuillade uses film and entertainment within the story as central plot points, and this mass media almost always leads individuals to danger or disaster: A dancer dies in the middle of a big performance; a large ballroom party dancing to music is drugged by tainted perfume. It reads as a reckoning of the precariousness of mass entertainment, with a tint of irony to it: it’s the most respectable displays (ballet; ballroom) that cause the most danger.

From the perspective of camera movement and editing, the film is fairly safe relative to innovation going on in cinema elsewhere at the time (e.g. Griffith): The large majority of shots are unmoving medium shots, as if filming a stage play, with linear stories and almost no cross-cutting between settings in the editing. Feuillade does inject small snippets of experimentation, though: Background action sometimes steals the eye from foreground action, hinting at the sophisticated use of deep focus by other directors in the years to come. Some of the compositions are truly marvelous given the era, too: The aforementioned ballroom dance party is arranged and shot like a Renaissance painting.

But even if The Vampires wasn’t especially groundbreaking in cinematic grammar, it pushes boundaries in story and character content. It’s easy to see this serial’s influence on (or at least prediction of) future crime film subgenres: gangster movies, film noir, heist stories, etc. Familiar plot points to those genres appear in primitive iterations in The Vampires.

Other than the length and the daunting more-is-less of the busy plot, the main thing that prevents me from giving this a recommendation to anyone other than curious film historians is that the heroes are so damn bland and corny compared to the crafty Vampires. I was always rooting for Irma Vep.

On screen, at least, it’s good to be bad.

Is It Good?

Nearly Good (4/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.