"We all go a little mad sometimes"

In his famous essay “An Introduction to the American Horror Film,” critic Robin Wood defined the genre: Horror is when “normality is threatened by the monster.” I don’t think every claim Wood makes in his piece holds water, but I do like his argument that the thrills-based genres almost implicitly function as psychological and/or socio-political commentary: The “monster” of the horror story, whatever shape it takes, automatically becomes a representation of a frightening “other.” Dealing with frightening “others” is an experience that drives much of our inner and outer lives as humans functioning in society, thus these movies often seem to be speaking about some broader concept connecting its audience to the material.

And yet, horror and thriller movies don’t require that layer to work as lizard-brain entertainment: a monster can just be a monster. Thus, genre films (I’m lumping horror and thrillers together here) become some of the most versatile pieces of art in cinema: In being great entertainment they often have more to say and think about through their metaphoric and thematic content than pure message or art films do. And they’re great entertainment to boot.

This is a major reason that Alfred Hitchcock’s films are so eternal. The Master of Suspense was sometimes viewed as a maker of trivial or crude thrills in his time, a sinister showman rather than an artist. And yet, according to the massive aggregation and scoring of best-ever lists undertaken by the team at They Shoot Pictures, he’s now the most critically revered director in the history of the medium, with a whopping 13 films on the site’s top 1000 most-acclaimed movies list. (Incidentally, a turning point in the Hitchcock’s broader critical repute was the 1965 book Hitchcock’s Films… by Robin Wood.)

I believe that Psycho, in addition to being an all-time masterpiece and one of Hitchcock’s greatest triumphs, makes a good entry point into the idea that great thrillers and horror films often speak to some broader condition of humanity even when their plot events don’t always make that commentary at face value. Hitchcock definitely had this idea in mind: We know that Hitchcock was obsessed with psychoanalysis, both from interviews and from content in his films, and that’s never more clear than in this film. He even named it Psycho! The film literally ends with a psychologist stating that the murderous behavior of Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is a reflection of the character’s delusions and hangups, his inability to adjust to the frightening realities of the world around him, and thus inhabiting a murderer’s form. Bates has, to put it mildly, mommy issues, which in turn barely mask sexual perversion and bloodlust. (The layers run even deeper than that: Perkins’ homosexuality was well known in Hollywood circles, which would have amplified the “ooky” factor for audiences aware of this; most of the US in 1960 had views “otherizing” non-hetero-normative sexuality.)

These days, that closing narration is typically regarded as the worst and stodgiest part of Psycho, and I agree with this assessment. But I’m still glad it exists, to some extent. It acknowledges just how deep the psychological well runs in great genre filmmaking. I kinda like that it makes this idea its closing statement. It’s partially why Psycho is a great entry point to horror movies for the layman. The nebulous concept of “why is horror meaningful?” is stated point blank. But, to Hitchcock’s credit (and something that plenty of 2025 filmmakers would do well to notice), the film is not actually rendered deeper by saying it out loud, and in fact becomes worse for it. I often think of something my dear friend Nate told me: He said that it doesn’t much matter what a movie has to say if it’s not a good piece of storytelling or entertainment. And if I may be so bold as to expand upon that rule with my own corollary: The better a movie is as a piece of cinematic storytelling (visually, narratively, tonally), the more likely it is to have some powerful ideas at its core worth thinking about. Psycho is one of cinema’s greatest movies, and because of that, one of its richest and its most thoughtful. (Not vice versa.)

Psycho opens with a camera drifting over a nondescript city skyline, landing on an arbitrary date, time, and window. There’s nothing sinister at face value about this opening shot, just the sun beating down on a Phoenix afternoon. But Hitchcock is already setting us up. By choosing a time and place seemingly at random, he’s telling us this story could be about anyone, anywhere; that there are infinitely many messed up people and stories hiding in ordinary life. It’s the last shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark, but in dreary reverse: cracking open an apartment at random and peeking what’s inside. The implication is clear, and will be echoed repeatedly throughout the film: Real horror isn’t an alien creature, even though it’s a “monster” of sorts. Rather, it comes from within ourselves and our own experiences, ones we often hide. Violence and perversion are scariest when they seep into our lives without warning. (Even the title sequence by Saul Bass, featuring fractured title block letters, hypnotic black-white patterns, and a Bernard Herrmann orchestra performing violent stingers, suggests normalcy gone haywire and evil.)

Inside that window: Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) and Sam Loomis (John Gavin), tangled in a lunchtime motel affair that is steamy but growing stifled. They want to be together in public but can’t, hamstrung by money, by circumstance, by social norms that make their honest passion into a moral compromise. Their relationship is already a conflict between inner, forbidden impulses and exterior reality, and that conflict becomes Psycho’s nucleus. And the process turns us filmgoers into voyeurs and peeping Toms (a concept he had explored in-depth in Rear Window a few years earlier.) Long before anyone sets foot in a motel shower, Hitchcock is probing how shame and societal pressure knot up our desires and destabilize us.

We are both sympathetic and anxious when Marion impulsively steals $40,000 from a lecherous oil baron client. Her criminal act doesn’t feel like a hard break, but a logical bid for resolving that tension. Hitchcock engineers our identification with her so deftly that we’re halfway into the getaway before realizing we’ve become her accomplice, pulled along through every one of her increasingly fumbled attempts at shedding the parts of herself that hold her back. Every cut, every shot, every glance is charged with suspense and danger. Psycho’s big twists and terrifying violence are what make it so famous, but this opening heist is its most riveting stretch, one of cinema’s most perfect acts.

Hitchcock shoots Psycho in stark black-and-white unlike most of his films from the era, which were usually shot in glorious Technicolor. (It’s his only pairing with cinematographer John L. Russell, and it’s a great one.) This visual choice has storytelling implications. It presents a bleaker, scarier, grayer world than, say, To Catch a Thief. The colors are black and white, but the morality certainly isn’t, as Hitchcock toys with Marion’s sin and guilt: Her “victim” is a vulgar, patronizing fat cat who won’t be hurt by the loss and is due to be brought down a peg. And yet from the outside, Marion is the “monster” here, the temptress who nicked a pile of cash to extend her torrid affair. Hitchcock erodes our moral resistance to pull us deeper into a moral sawmp.

Marion’s escape with the forbidden money curdles quickly. Her initial thrill at escape fades, and she feels more trapped than ever. She is visibly rattled. Hitchcock lingers on her face and her gaze: eyes darting to the rearview mirror, tension in her posture in the driver’s seat, and the rhythm of her inner monologue quickening. Her crime becomes less about the money than about her accepting some dangerous side of herself.

As Marion drives further from the city, deeper into the wilds, her grasp on reality begins to fray, setting us up to be completely jarred in a few scenes. Hitchcock tightens the frame around her, traps us in the car with her. We hear imagined voices, conversations she’s replaying or pre-playing in her mind. Every headlight behind her becomes a world-blurring threat, every cop a harbinger of purifying justice for her sin, every drop of rain a promise of absolution (violent absolution, as it were). We probe deeper into Marion’s psyche: thinking like her, spiraling with her.

Threading through all of this is one of the movie’s singular achievements: Bernard Herrmann’s iconic and deeply influential score, sharp and needling as Marion’s thrashing conscience. This uneven, jolting musical texture is still the basic sound of scary movies. (The most obvious successor is John Carpenter’s Halloween, and it’s far from the only inspiration Carpenter pulled from Psycho.) Those strings don’t just signal tension, they are tension, frayed nerves rendered into sound waves. Herrmann elevates moments that might otherwise feel still: Driving in silence becomes intolerable, in part because those strings could strike at any moment

And then, through a fogged windshield, we see those fateful words: Bates Motel. By the time Marion arrives, she’s soaked, exhausted, and unraveling. The place feels like the dead end that it (literally and figuratively) is: tucked off the highway, half-forgotten, surrounded by nothing but rain and swamp and shadows. (Norman repeatedly notes the “old highway” once passed by it, an evocative turn of phrase.) Hitchcock shoots it like a bad dream: neon flickers, empty rooms, steep angles. Every image we see through Marion’s eyes careens with deathly portent: A mansion on a hill, peering down; the purgatorial motel rooms, shot boxy by Hitchcock so they are closing in on her; the motel parlor filled with ghostly birds (a symbolic fascination Hitchcock would explore in depth a couple years later). In a different movie, this sequence would be setting us up for a chase and escape, but Hitchcock has something more seismic planned.

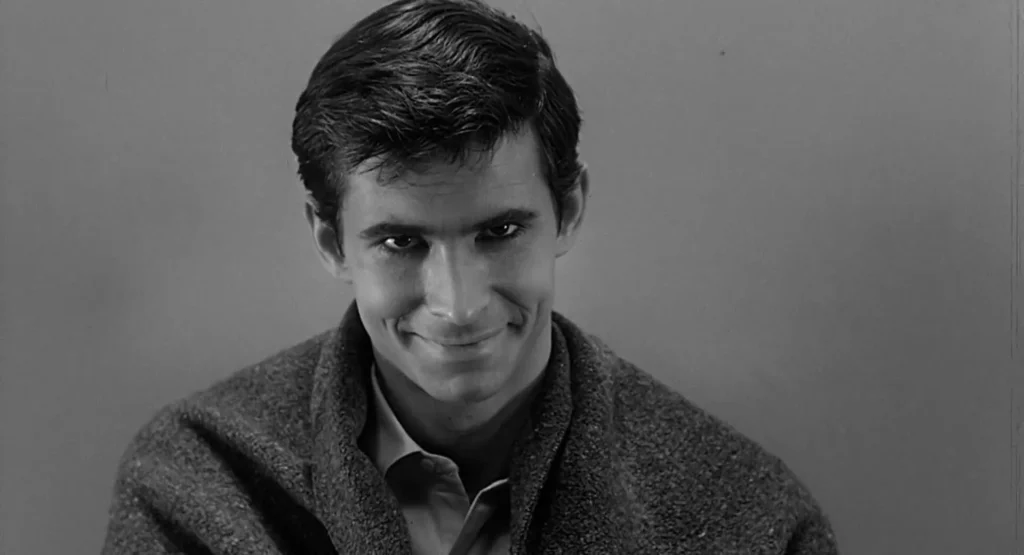

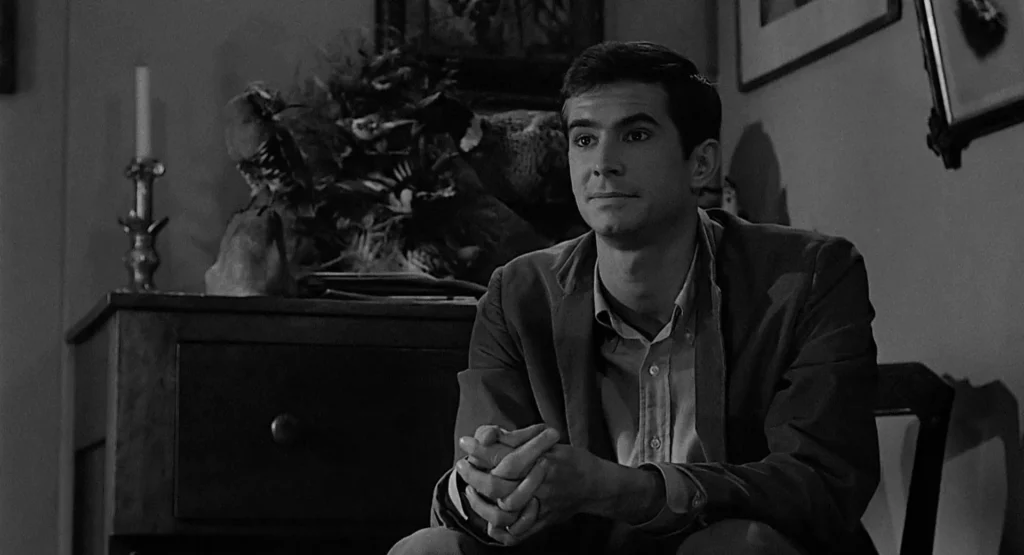

A new face enters: Norman Bates, all stammer and charm, and the film’s psychological terrain shifts. Marion checks in, and they have a dinner conversation in the parlor that is disarmingly gentle but charged. They talk mostly about Norman’s unwell mother, and what to Norman can do about that sad and heavy burden. It’s a conversation that plays much richer the second time watching, once we know where it’s all headed. Norman’s talk of “private traps” particularly lingers: suggestions of twisted impulses (and sexuality) bearing us down and pulling us away from respectable “normality.”

For just a moment, Hitchcock teases us with the idea that Marion might actually get off scot-free. She scribbles out the numbers, flushes her guilt down the motel toilet, and smiles with a clarity we haven’t seen since the film began. And then, without warning, Psycho rips that hope away, and more. The moment she steps into the shower (Norman a voyeur, like us), the narrative dissolves. Marion’s death is one of those points in the history of cinema, like the opening shot of Star Wars or Dorothy stepping into Oz, that seems to expand the horizons of popcorn films as an artform. Narratively, the film loses its center, one whose centrality and sense of perspective had been so fundamental to the film’s opening half. And thematically, the film embraces the darkness and macabre of our inner lives. She cleaned her body moments after she believed she had cleaned her soul, only to find that there’s no escape from the sin and moral tension.

The shower scene doesn’t need more superlative poured upon it, but here’s some anyway: It remains shocking and terrifying 65 years later. Hitchcock strips the moment to its elements — blade, scream, blood, tile — and slices it into 78 exacting edits. The violence is abstract, almost balletic, and charged with sexuality thanks to Janet Leigh’s almost orgasmic expressions under the falling water. Herrmann’s screeching violins are an assault. Her death is fast and impossibly final, collapsing the story and our illusions of safety in the same breath. The water keeps running, like nothing happened.

And something even stranger happens just afterwards: the camera stops centering on the the corpse of the ex-heroine. It starts following Norman. Hitchcock tilts our gaze toward the aftermath, the meticulous cleanup. Suddenly we’re watching Norman with the same intimacy we gave Marion a couple scenes earlier, tracking his uneasiness at the mess he’s in. He scrubs away the blood and frantically disposes of the body and her vehicle. We witness it unfolding methodically and from his perspective. Just like Hitchcock suggested anyone’s sin and circumstance could become crime like Marion’s, now we’re in on this murder, too. Hitchcock dared us to sympathize with Marion; now he double-dog-dares us to do the same with Norman. Though we haven’t yet seen just how culpable he really is, the sense that we’ve been sucked into the same mire that swallows Marion’s car pervades the rest of the film.

What makes that shift in perspective bearable, almost seductive, is Anthony Perkins’s performance. Norman Bates is one of cinema’s great paradoxes: boyish and bashful on the surface, coiled and murderous underneath (spoiler, sorry). Perkins plays him with such calibrated awkwardness that it takes a while to notice how off he feels. He’s handsome and a little charming, but his demeanor shifts every minute or so, with something reptilian in his expressions, like there’s some great ocean of danger and instability just under the surface. That Perkins didn’t receive an Oscar nomination ranks as one of the great snubs in the Academy’s long history of them.

The second half of Psycho isn’t as breathless as the first, but it’s even more provocative. The camera unhooks from one woman’s panic spiral and cools into a procedural: the worried sister Lila Crane (Vera Miles), the boyfriend Sam, and the private eye Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam) start hunting for Marion, inevitably finding their way to Bates Motel. But the perspective we spend the most time with is Norman’s: he scrambles to hide his “mother’s” heinous acts in his haunted house and abyssal swamp.

What’s most satisfying post-Marion’s death is how ideas from the first half of the movie are echoed, elaborated, or flipped in borderline dream logic. The film keeps returning to images of hands and eyes: Marion’s white-knuckle grip on the steering wheel becomes Arbogast’s open-palmed reach for the banister. The peeping eye of Norman and the dead eye of Marion becomes the gaping void of Mother’s eye sockets. Where Marion and Sam started the film with sweat and secrecy, Sam and Lila become a couple themselves, albeit a strictly fake and utilitarian pair committing stakeout. Eating turns inside out, too: Marion’s sandwich in a parlor becomes acidic digestion (and regurgitation) of a swamp.

Hitchcock also engineers a nasty vein of dramatic irony in the film’s second half. We know Leigh is dead; the film knows we know; and yet it steers Balsam, Gavin, and Miles along a rescue mission. The $40,000 becomes a cosmic prank. Perkins doesn’t even clock it — he flings the newspaper holding the cash into the trunk like it’s another messy scrap of cleanup, which then sinks into the decaying earth. For the investigators, the cash is the key to the story; for the audience, it’s a nothing but green paper over the more sinister truth.

Meanwhile, the camera can’t stop gawking up at that house on the hill, and who can blame it? The Bates place is one of horror’s most potent images — an American Gothic containing not just the broken psyche of its characters but the rotting sociology of all of Hitchcock’s postwar American audience. It has a tantalizing siren call; even if we don’t know the truth, we detect something dangerous within dying to get out, like it’s Pandora’s manor. Every character who approaches it gets pulled a ring deeper into its orbit: Marion gazes from the motel lot, a pilgrim staring at a forbidden temple; Arbogast steps across the threshold and is sent tumbling back down the steps like a rejected offering; Lila descends into the cellar and discovers the shrine itself, ripe and vile, where sex and death and pain have been embalmed into a single, leering idol. The shot/reverse-shot grammar gets kinked whenever the movie takes us inside, throwing us off kilter. Angles steepen; ceilings loom. Hitchcock’s dollhouse turns into a dissection of the human psychology: the stern superego upstairs, the anxious ego at ground level, and the sweaty id kept in a cellar below. Two decades of slashers are born right in that cellar, the one holding horror’s greatest and dirtiest secret.

By rights, the revelation of Norman and Mother being one should be a laughable, cod-Freudian eye-roller. Instead, it’s one of the greatest twists in cinema (the second great one in this very film!). Everything in the movie builds to this moment, and it delivers. Thanks to Hitchcock’s camera and Herrmann’s strings, it’s a soul-freezingly effective moment, even when you know what’s coming: The desiccated skull of Mrs. Bates, the deranged look on Perkins’ face as Norman “inhabits” her, every guilty impulse we’ve tracked in the cast of characters — lust, shame, greed, wrath, envy — comes roaring together in the cellar and crashes over Lila and the audience. Sam arrives to play hero; but watch to Perkins’s moaning face as he’s pinned: it echoes Leigh’s earlier shudders in the shower, his gasps not just one of defeat but of annihilation and, yes, orgasm. Sex and violence, mommies at the cradle and loved ones at the deathbed, saviors and psychos — all tied together one perfect, rotten knot. “Deadfuck” indeed.

Now we’re back where I started this review: the postmortem from the psychoanalyst, laying it out there for us in too many words. But that’s not really the end. Norman Bates gets the final: “I wouldn’t even hurt a fly,” his face momentarily merging with the skull via editing dissolve, the car dredged from the muck. Normality is indeed “threatened by the monster” over these 109 minutes. But Psycho’s coup de grace is to convince us that “monster” and “normality” are, in fact, one in the same. The “monster” is the mental sickness infecting us all, begging us to watch like Norman through his peephole: It’s in the house on the hill, and in the motel office, and in the parlor’s birds, and in the Phoenix window we picked at random — all captured in some of cinema’s finest filmmaking by one of cinema’s finest directors.

Psycho remains the ultimate gateway drug for horror-skeptic movie lovers and an enduring summit for the converted. It’s one of the cinema’s great arguments for how style, structure, and story can surface the things we’d rather not dredge up.

Is It Good?

Masterpiece: Tour De Good (8/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

2 replies on “Psycho (1960)”

Hidey-ho, Murderinos!

Somewhat to my embarrassment I’m mainly popping in to confess that, while I’ve seen at least one of the sequels and the Van Sant cover version (I remain deeply disappointed that the latter didn’t have the nerve to cast Ms Julianne Moore as both Crane sisters), I’ve never actually seen the original.

Also, whenever I see photographs of Mr Anthony Perkins from this era I think “If they had Hollywood superhero movies at that point, that dude was born to be their Spider-Man”.

I can’t say I’ve ever met anyone who has seen only the Van Sant remake! You’re in rare territory! But the original is 100% worth a watch — it’s one of the greats for sure. I think I had it at #34 last time I made a top 100 favorite movies list, and I suspect it would inch up a few spots if I made one today.

Man, Julianne Moore is in the Van Sant as one of the Cranes? That’s great casting. I really oughta give it a try sometime. The idea of double-casting the Crane sisters is a fun one that would play with some of the symbolic stuff the characters do in the story. (Especially because they never appear on screen together.)