Thank the Phoenicians

One reason the release of every Wes Anderson film is an exciting occurrence is because you can reliably count on him to push his aesthetics or storytelling in some bold new direction. Despite persistent accusations that Anderson fossilized around Zissou, endlessly riffing on the same visual quirks and narrative obsessions, the truth is exactly the opposite. With each new outing, Anderson has exploded his meditations on life, death, and human nature into ever more intricate expressions, sharpening his already planimetric mise-en-scènes into near-baroque levels of lively artifice. He remains defiantly uncompromising and never dull.

The only arguable exceptions to Anderson’s pattern of presenting a new frontier with each release are The Darjeeling Limited and, now, The Phoenician Scheme. Not that either of these films is even remotely unsatisfactory. I’m extremely fond of both. But they feel a little safer and less bold within their place in Anderson’s arc than most of his other films. Yet, even that take doesn’t quite hold up under scrutiny, because both Darjeeling and Phoenician deliver plenty of subtle innovations; they’re just quieter, less obvious breakthroughs.

The easy read on The Phoenician Scheme is that it’s Anderson back in familiar territory: a family-centric adventure reminiscent of his first five films. Its narrative is linear and direct, almost schematic. The opening act literally places before us a series of “boxes” that represent the forthcoming episodes the characters will participate in. And, like many of Anderson’s earlier films, almost all of those before The Grand Budapest Hotel in 2014, it revolves primarily around navigating or repairing the strained bonds between a parent and child.

But the easy read is reductive. To me, The Phoenician Scheme is more in conversation with the introspective Asteroid City than to the familial angst of The Royal Tenenbaums or The Life Aquatic, despite obvious narrative parallels to the latter. Like Asteroid City and sections of The French Dispatch, this film is Anderson confronting his own life’s work and purpose, albeit more obliquely (and humorously — this is Anderson’s funniest work in years, maybe ever). When Anderson makes movies about his own filmmaking, it’s not just navel-gazing. Instead, his look at his own process serves as metonym for a reflection on deeper truths of storytelling itself: how narratives give shape to our experiences and allow us to connect meaningfully with the past and the world around us, allow us to confront unknowable truths like mortality and suffering.

Specifically, The Phoenician Scheme grapples with legacy — what happens to our creations after we pass, the reasons and methods by which we pass down something to the next generation, and how we might ultimately be judged by our contributions. Throughout the film, the characters wrestle with how to “fill The Gap,” a phrase carrying both literal plot significance and symbolic heft. Notably, for the first time in his family dramas, Anderson’s perspective aligns more clearly with the elderly parent rather than the younger adult struggling with inherited baggage.

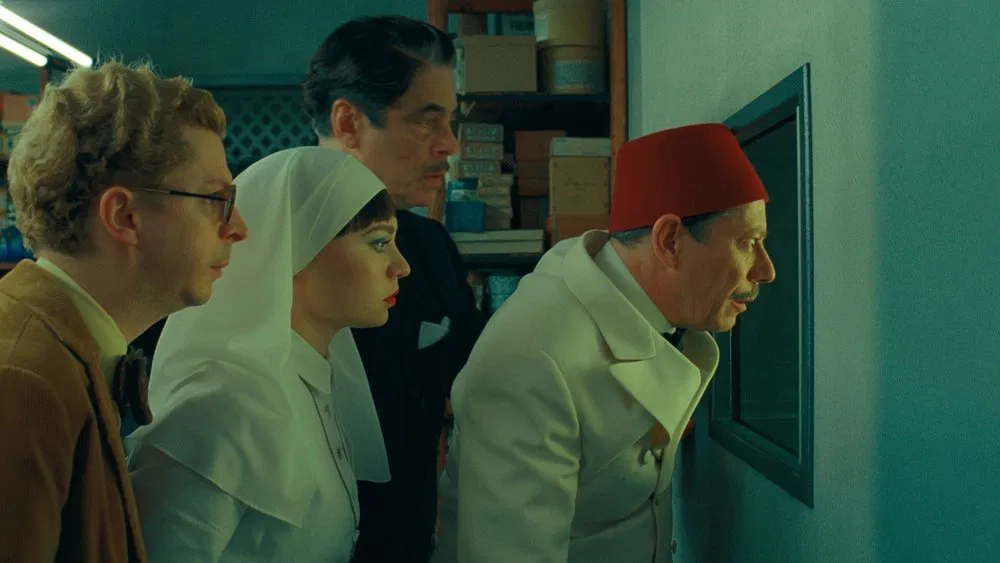

The Phoenician Scheme’s plot is an espionage caper centered on Anatole “Zsa-Zsa” Korda (Benicio del Toro), a notorious billionaire involved in international conspiracies. His brushes with death due to strangely-frequent, miraculously-survived plane crashes trigger visions of the afterlife. These confrontations with mortality prompt him to reconnect with his estranged daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a nun-in-training.

Korda ropes Liesl and the family’s tutor and assistant Bjørn (Michael Cera) into an ethically dubious scheme to fund an infrastructure of a fictional country called Phoenicia using slave labor and extorted capital. Global powers, rival investors, and a steady stream of would-be assassins conspire against him. He and Liesl race to “fill the Gap” in funds to complete their mysterious infrastructure project as US agents use their entire means to slow down (or eliminate) Zsa-Zsa.

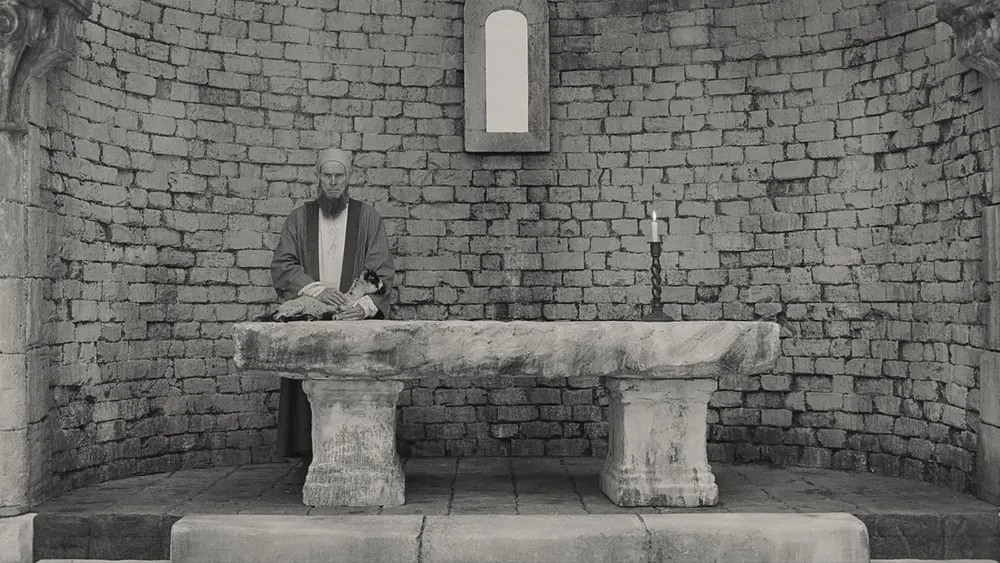

Despite frequent allusions to heaven and judgment (even featuring Bill Murray as God Himself) The Phoenician Scheme actually feels less spiritually probing than Asteroid City, in which dreams and aliens and stories are vessels to the great beyond. Here, religion acts more as a morality gauge than a mystical portal to the unknown. This film suggests our true worth is shaped less by a relationship with a creator than by how we treat one another and impact the tangible world.

Anderson crafted this story to honor his late father-in-law, Lebanese engineer Fouad Malouf, yet the director clearly found his own entry point. Zsa-Zsa’s elaborate and controversial Phoenician enterprise, repeatedly sabotaged by covert U.S. government intervention, feels like Anderson speaking through his own idiosyncratic lens about the struggle of maintaining an uncompromising creative vision in hostile Hollywood. It’s sad that Anderson continues to frame his creative identity as something perpetually besieged and misunderstood, a recurring theme especially in recent years. (Also, it’s a bit confusing… Anderson maintains remarkable creative freedom and consistent budgets, plus positive reviews and reputation among Hollywood creatives.)

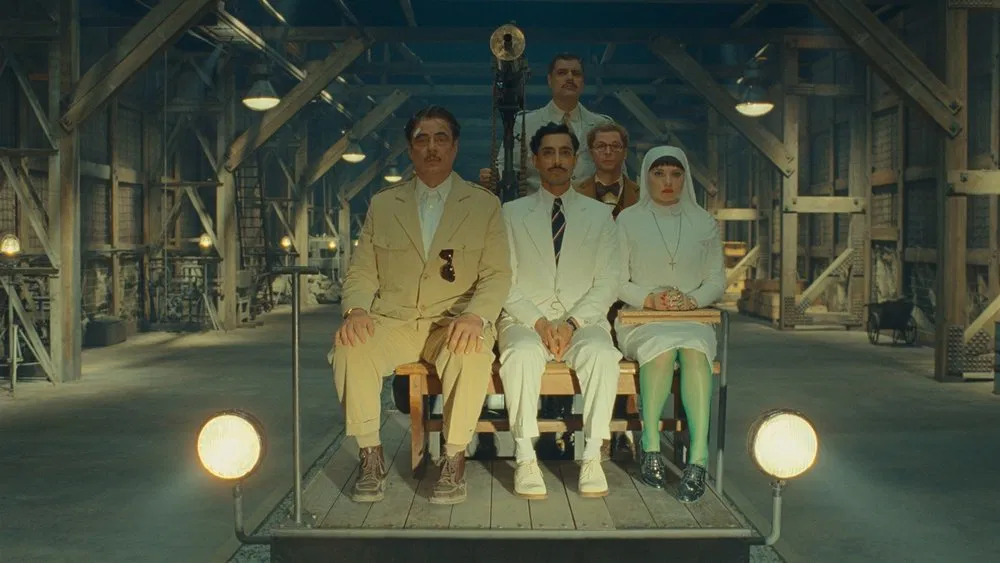

The cast is uniformly excellent, each actor locked into Anderson’s precise comedic and dramatic rhythm. Del Toro is nothing short of extraordinary, embodying Korda’s ruthless charisma with both humor and an aching melancholy. Meanwhile, Cera proves himself a natural Anderson muse, bringing his terrific comic timing and dorky persona to Bjørn’s mild-mannered absurdities. Threapleton, Kate Winslet’s daughter, delivers a solid performance as Liesl. It evokes the iconic, low-key Gwyneth Paltrow turn in The Royal Tenenbaums. Watching Threapleton navigate Liesl’s slide into her father’s cutthroat universe is a delight, as you can detect her own youth and hunger. Threapleton is not quite as naturally in tune with Anderson’s style as fellow newbie Cera is. Still, I’ll be curious to see if her career takes off from here.

As with any Anderson project, even the smaller roles are filled with wonderful turns from Anderson’s reliable and ever-growing stable of character actors, plus a few fresh Anderson faces. Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston make a hysterical pair of investors who settle business disputes with rounds of Horse, while Benedict Cumberbatch’s late-film appearance as villainous Uncle Nubar puts the actor in some outrageous physical comedy making use of his stretched face and lanky frame. Willem Dafoe, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and F. Murray Abraham, along with Murray, pop up as afterlife entities, once again affirming Anderson’s penchant for casting world-class actors in even the most fleeting supporting roles.

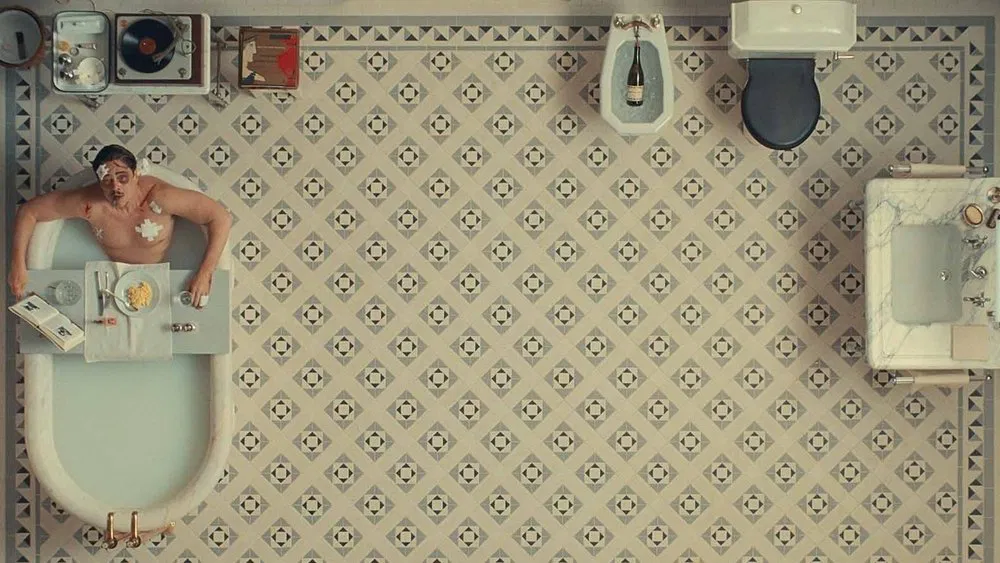

From a formal perspective, The Phoenician Scheme slots comfortably into Anderson’s established visual style, with one major behind-the-scenes shift: cinematographer Robert Yeoman, who shot every live-action Anderson project to date, has stepped aside, replaced here by Bruno Delbonnel. Delbonnel mostly delivers a respectful Yeoman imitation, yet subtle but noticeable differences emerge: the lighting is a bit softer, the color grading is punchier and darker, the textures are just a touch grittier, the central subject of compositions is less intuitive. Anderson leans even more heavily than normal on his trademark panning shots, repeatedly swiveling precisely 90 degrees. He also throws a few uncharacteristic moments throughout — memorably a top-down credits shot so striking it’s been used in marketing, and an especially an alien-feeling handheld shot during the climax (to my memory, a first for the director). Still, this remains unmistakably an Anderson film.

(I haven’t seen any sourced reporting on exactly why Anderson is working with Delbonnel rather than Yeoman this time around, though multiple rumors online cited Yeoman burning out on Anderson’s ridiculously prolific output in recent years.)

Alexandre Desplat, Anderson’s composer for many films now, provides the score, and once more the results are superb. Desplat’s tone perfectly matches Anderson — whimsical and colorful on the surface, but melancholic in mood. It’s easily one of the best scores of the year so far, second only to Ludwig Göransson’s stirring work on Sinners in my ranking, and another confirmation that Anderson and Desplat remain one of cinema’s greatest contemporary partnerships.

Even if it’s a hair safer and more narratively simple than Anderson’s most audacious works, we should never take a master operating at peak powers for granted. Anderson’s signature deadpan barely covering a bleeding heart and wounds of lost time remains eternally satisfying. That The Phoenician Scheme ranks closer to the median rather than the very top of Anderson’s filmography is no slight; it’s simply a reflection of how consistently visionary Anderson is, how powerful his filmmaking has remained for more than a quarter century. He has a style unmistakably his own, a clear voice with meaningful things to say, and I will rejoice in every opportunity to see him create.

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

2 replies on “The Phoenician Scheme (2025)”

Y’know, I’m kinda eager to give this a rewatch, as maybe I missed the keener emotional hooks that do seem to have found others, and it doesn’t have the open bafflement of Asteroid City that made me nervous to revisit it (though having done so, and confirming that bafflement was the point, it wasn’t at all unpleasurable).

This one snuck up on me, for sure. I kinda want to watch it again too because other reviews have made it seem more religious than I personally felt it was (despite the plot and afterlife imagery). My wife slept through the second half and she was mad she missed it so it probably won’t be too long for me.