The passion of the Gance

Silent cinema is full of legendary figures, but none is quite so mythic as Abel Gance. Gance was a prolific director whose career spanned well into the sound era, but he is primarily known today for three silent epics. They are, in ascending chronological order and critical legacy: J’Accuse (I Accuse) from 1919, La Roue (The Wheel) from 1923, and Napoleon from 1927. (All are typically known by their French names.)

They are each singular works, but collectively among the most influential silent films ever made, presaging editing, lighting, production, camera, and composition techniques of many subsequent film directors and movements, most especially the Soviet montage films. But all three epics were largely unwatchable for decades. For numerous reasons — including their prodigious length, their unusual projection requirements, their mixed contemporary reception by critics, and Gance’s habit of constantly re-editing his films — each languished in archives as snippets and partial versions. But in a heartwarming, happy ending, all three have undergone herculean restoration efforts and are now, or will soon be, accessible to film fans in versions closely matching Gance’s original cuts: J’Accuse was restored and issued on DVD in 2008. La Roue has had two major releases — one in 2008, one in 2020. Napoleon’s recovery is the most historic and unlikely of all, and I’ll discuss it in more detail when I review it, but the culminating restoration finally debuts later this year in Paris.

Beyond the dubious extancy of his ambitious opi, the reason that Gance is such a mythic figure is that his films are the ne plus ultra of grand ambition and tragic destiny: Each epic he directed is titanic in length, scope, and melodrama. Many of the creative forces involved in La Roue lived dramatic lives and died dramatic deaths, and the production swirled with its own mythology. Gance suggested in letters, without explanation or evidence, that he was the victim of a blackmail conspiracy at the time La Roue was in production. The only script (”scenario” as it was called in the silent days) existed in a leather-bound book that Gance kept by his side at all times and refused to show anyone else. When it was finally recovered decades later, the script bore only a loose resemblance to the final product, suggesting Gance had written much of the film in his head alone. Multiple figures involved in production, including star Severin-Mars, died within a year of the premiere. In fact, Severin-Mars died in 1921, shortly after shooting completed, more than a year before the premiere.

It’s the kind of picture that cinephiles speak about in hushed, reverent tones. Its style is off the charts: Gance shoots the most intense and expressive close-ups, the richest deep-focus shots, the most awe-inspiring epic long shots. His montages are chaotic, rhythmic, impressionistic masterpieces; his extended shots, usually on human faces, are almost excruciating in their patience. He remains one of cinema’s great image-makers in the medium’s history.

La Roue’s two modern restorations and releases, the 2008 and 2020 cuts, run 263 and 414 minutes, respectively. The 2020 cut is the one I watched and is regarded as the closest to Gance’s original 1923 version. You read that minute count correctly, by the way — this is a seven-hour film, though it’s not quite as daunting as it sounds. La Roue was designed and screened as a serial: four parts, each shorter than 2 hours, telling a continuous story. In other words, it’s closer in format to a season of White Lotus than it is to Oppenheimer. Most Gance fans I’ve encountered recommend watching it in chapters rather than a marathon sitting, and broken up is how I watched it. Gance himself screened the film across multiple weeks at its premiere.

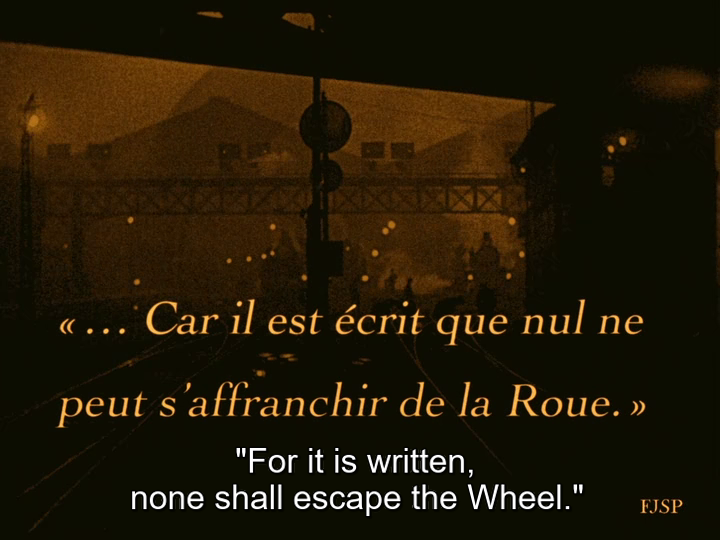

Among Gance’s many innovations were some groundbreaking use of intertitles. Whereas most silent filmmakers used intertitles as a functional necessity to convey information or dialogue, Gance used them as part of his artistic repertoire: The text in La Roue uses a huge variety of font faces, sizes, and styles to capture the spirit of that moment of in the story. The text is sometimes imposed over existing shots or accompanied with double-exposed images. Gance embedded a deep and flexible love of language into the intertitles: some of the film’s text is quotations from other works; some of it is written in a poetic format; and some of it is starkly minimal.

Gance applied every technique then known to movies to La Roue: Shots both stationary and moving (often attached to trains); dynamic irising such that the shape of the frame sometimes shifts mid-shot; and lighting that leverages some techniques from German expressionism in warping reality, but with less harsh chiaroscuro artificiality. The careful lighting on faces, in particular, takes the evocative close-ups from Intolerance and explodes them into an entire art form. Post-production includes multiple-exposure, tinting, and hand-coloring.

La Roue is the closest cinematic equivalent we have to romantic-era literature: Gance was deeply inspired by the aesthetics and philosophy of romanticism and can be classified as a neo-romantic. La Roue’s huge scope, decades-long narrative, and chapter-segmented structure give it the shape of an epic novel. The central character, Sisif (played by Severin-Mars), is a howling storm of passion and self-defeating impulses, an heir to Heathcliff. The saga is protracted and operatic, filled with unrequited passions and suicidal temperaments and deeply-guarded secrets and heartbreaking deaths.

Even beyond the structure and tone and its thoughtful use of language, La Roue is an extremely literary film, most clearly in its use of symbolism. The film is drowning in symbols. The central symbol is the wheel, ever turning, crushing specks of dirt beneath it, the highs and lows of any one point on its surface rising and falling in proportion with the fates of others. Every element of human existence — comedy, tragedy, dreams, realities, love, fury, etc. — is a spoke, holding together that wheel we call life. This idea is reflected in both the multitudinous content of the narrative and the ever-shifting form and genre of the film itself. Circular images abound in La Roue, most notably in the chaotic opening sequence of a crashed train: the wheel is, above all, a force of industrial modernity demolishing all of life and nature around it.

Other favorite symbols of Gance’s in La Roue are the train and the rail — one-track paths of unstoppable destiny. The rail curves around hills and through tunnels, but continues inexorably forward. The train, meanwhile, is a force of power but also destruction, the object that holds the community together, but disrupts the quaint, pastoral life of Sisif’s household. This is captured visually by placing the train station so close to Sisif’s quaint cottage that they appear in the frame at the same time, a horrifying and unnatural adjacency. The train is the anchor of Sisif’s life: When he falls in love with Norma (Ivy Close), his instinct is to name his train after her; to project his undying passion upon the unceasing engine.

With these symbols and more, Gance develops an associative language of cinema: When we see a scene or an image, its purpose is to evoke a heightened feeling or a link between two ideas as much as it is to advance the story. In fact, the story itself is thin on actual plot points for a feature-length film, let alone a seven-hour epic.

A warning if you are concerned about spoilers for a century-old film. The rest of this post will discuss La Roue’s full story and my overall take on the film, including discussion of the ending and major twists.

The film opens with a train crash, and it is one of the best moments of the entire film. In an extended, red-tinted montage, death and chaos overcome a little village. Sisif, a young man working on the rail, rescues a toddler girl whose parents perished. He names her Norma. Sisif already has his own son of a similar age to Norma named Elie (Gabriel de Gravone).

Years later, Sisif closely guards the secret that Norma is not his real daughter. Now a middle-aged alcoholic, Sisif has grown protective of Norma, who has become a beautiful young woman. He fends off local bachelors looking for a wife — including his well-financed colleague Hersan (Pierre Mgnier). He also casts a weary eye on his son Elie, now a violin-maker, who shares close affection with Norma, whom Elie believes to be his sister.

One day, in a drunken stupor, his finances in ruin, Sisif confesses to Hersan both that Norma is not really his daughter, and that he has fallen in love with her himself. Hersan immediately uses this as blackmail — he agrees to keep Sisif’s secrets so long as Sisif lets Norma marry Hersan. And so Norma gets married off and moves out of town.

This sets off an even darker spiral for Sisif, culminating in his being blinded in a steam engine mishap. Meanwhile, Elie discovers evidence that Norma is not his sister, which triggers his own realization that he had fallen in love with her. Elie begins to spiral himself, and he starts to bear his father’s obsessive and alcoholic tendencies.

It comes to a head in a mountain excursion for Sisif and Elie as they vacation near Norma’s new residence. Norma, unhappy in her marriage, crosses paths with Elie, who tries to confess his love in a message written on the inside of one of his violins. Hersan discovers the message, and Hersan and Elie get into a bloody fight that ends with Elie literally hanging from a cliff. The vision-impaired Sisif is not able to save Elie in time, and Elie crumples to the foot of the snowy mountain, dead.

Years pass, and Norma leaves Hersan, moving back in with Sisif, whose vision is slowly returning. The two eventually find solace in each other as life partners, quasi-romantic, quasi-familial. One day, Norma is invited to participate in a maypole-style festival. An aged Sisif passes away as he watches from a window, his final view a blurry wheel of dancing people, including the love of his life, Norma.

It is a melodramtic film, and a troubling one, too: Obviously the story of a father and a brother falling into a love triangle with their daughter and sister, respectively, is a bit disturbing. This is even more true in the early stretches, when Norma is coded with imagery of a child — playing on a swing and picking flowers. (Ivy Close, Norma’s actress, was about 30 during production.) Gance is at least aware of this ookiness, and also aware of the powerful connections to literary history it invokes: He directly quotes Sophocles’ Oedipus on screen, whose story Sisif sometimes echoes.

The entire 7-hour story hinges on the three family characters: Sisif, Norma, and Elie. Thankfully, all three leads offer terrific performances; Close as Norma and Severin-Mars as Sisif, in particular. Each need to accompany no less than half a dozen roles and archetypes throughout, and do so wonderfully. Both find tremendous expressiveness in subtle facial expressions and movements during numerous close-ups. I wonder if Severin-Mars’s performance would be talked about in the same way that Maria Falconetti’s in The Passion of Joan of Arc is had critics had better access to the entirety of La Roue as the film canon was taking shape.

With its stormy narrative and tremendous imagery comes a really overwhelming sweep to the film’s most climactic moments, often shown through montage: In addition to the film-opening train crash, the most powerful moments of La Roue are Elie’s death and the very finale of Sisif’s passing. During Elie’s death, which includes a “life flashing before his eyes” sequence, and its aftermath, in particular, I briefly wondered if La Roue was worthy of this site’s highest rating. But I can’t get there. The film is exhaustingly laborious to modern eyes, even split into chunks. There is something of value in that, of course; La Roue is a rare film that not only challenges you to stare at images like unceasing facial close-ups and messy rooms and steamy trains for hours on end, but actually gives you a real payoff for all that effort.

There is a sublimity to the way La Roue imposes its philosophy. Gance was obsessed with the way that desires of all sort shape us, and that we only achieve spiritual enlightenment and actualization once we can shed them. His entire film considers the way that Sisif — named after the Greek mythology figure Sisyphus — bears boulders of earthly suffering as a result of his desires: for sex, for romance, for wealth, for independence, for lost family. And only as he lets go of Norma so that she may go dance and be a part of nature and communal pleasures in the final scene can he pass through the portal that separates life and death. He has, finally, shed his desires, and so he may depart.

As powerful as La Roue can be for certain stretches, as unforgettable and profoundly touching as its images are, I can’t say I’ll ever watch it again. It’s often impenetrable. Not helping are baffling discursions: out-of-place slapstick comedy drags down certain sections, and the long-gestating setup on the future of the rail business early in the film basically disappears. A few characters are introduced and forgotten, including a bizarre character named Kalitikascopolous who I think is supposed to be a racial caricature, but one I did not register.

La Roue, though challenging to watch, is a brilliant film that achieves an apotheosis of the melodrmatic and neo-romantic forms of silent cinema. Gance called movies “music of light,” and he composed a visual symphony in La Roue. French filmmaker Jean Cocteau declared it the most seminal film in history, a European counterpoint to The Birth of a Nation in singlehandedly grappling with and shaping a nascent cinematic language. But unlike Griffith’s epics, La Roue remains a sui generis masterwork rivaled only by a few films among all of silent cinema (including his later Napoleon) in its novelistic ambit.

Thanks to J. J. over at Zepfanman for his terrific overview of the two restorations.

Bonus Article: 101 Images from La Roue

Is It Good?

Very Good (6/8)

A few words on "Is It Good?" ratings for early cinema.

Follow Dan on Letterboxd or Twitter. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

4 replies on “La Roue (The Wheel) (1923)”

Great review, Dan. It’s been on my radar for a while, but I dunno. The last European seven-hour consensus masterpiece bursting with bombastic style that’s actually a television show that I watched, Bondarchuk’s War and Peace, was something of a wet noodle. Would move up in priority if I ever get to see Napoleon and enjoy that (I have more affinity for the subject matter of the 1927 film, and, anyway, if I want to see the story of La Roue I bet half the frontpage of Pornhub has a remake). And I do have a sort of problem with seven hour movies: as a movie, I’m sort-of honorbound to finish it if I start, in a way I’m not with TV shows, so that I can’t watch the first hour of it and decide its psychedelic piss color grading was the ugliest fucking thing I ever saw and quit, ala, as you say, White Lotus.

I actually own La Fin du Monde as an outgrowth of my interest in 30s disaster films, but haven’t watched it yet.

Not a real criticism, but don’t want you to get yelled at: might append a spoiler warning. I mean, I know, I know, I do…

Thanks, Hunter. I added a little spoiler warning at your suggestion.

The natural entry points on Gance’s silent epics are either J’Accuse (his first) or Napoleon (his last and most famous), so naturally I went with the middle one. (The real reason is that it showed up on my slow crawl through the chronological listing of 1001 Films You Must See Before You Die.) I’m excited to watch Napoleon someday, but also excited to watch some non-7-hour films in the meantime. Actually, our friend Gavin has tickets to the premiere of the restoration in July, and I’d probably be flying across the Atlantic to join him if I didn’t have two kids that require annoying stuff like being fed and supervised.

Enjoyed reading your thoughts on this. If you ever have the urge to watch it again with a friend, try the shorter 2008 cut – it’s really a good distillation of the essential elements.

Glad you found my overview of the restorations helpful. I wasn’t able to find a full summary of each part online, so I created it myself – I hope it was accurate. I had trouble determining the passage of time in the second half of the film.

Thanks for finding me and commenting J. J.! And thanks for your overview and review — very helpful. If I ever watch again, I’ll definitely think about the shorter cut. Agreed that the timeline is not super-clear, though it obviously spans a long time (decades by my read).