Earn this

It takes a special breed of actor for the name alone to be a brand and a promise to the viewer, but Douglas Fairbanks achieved that during his career. You bought a ticket, and you knew what you were getting: a buoyant, acrobatic adventure in exotic trappings; a roguish hero who leaps and flips around the frame; and a signature stance: hands planted on hips, chin tipped to the heavens, as if gravity itself is an unworthy foe. His most acclaimed films came during the silent era, which means his cultural stock has dimmed a bit as the pre-talkies in general have, but The Thief of Bagdad is proof by itself that Fairbanks should endure. It is Fairbanks’ grand opus and the purest distillation what made him irresistible: movie star charisma weaponized into motion, blood-pumping adventure, and sheer film joy with a stuntman’s bravado and a painter’s artistry.

Fairbanks did not direct his films, but he was also much more than mere poster-ready face and figure. He was the producer and organizing voice of many of his films. Though Raoul Walsh has the director’s credit for The Thief of Bagdad, Fairbanks was its mastermind: He produced the picture, conceived the scenario (with screenplay credited to Achmed Abdullah and Lotta Woods), coached artists designing the storyboards (sketching some himself), hired the creative team, set and enforced the shooting schedule, and then turned around to sell the whole enterprise to the masses like a huckster. He’s the adventure film equivalent of Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, a real “auteur” before the term emerged. That unity and clarity of authorship renders the film’s clean narrative line and visual experience, ensuring every set piece is tailored to his strengths.

Because he was handsome and famously athletic, it’s tempting to write Fairbanks off as the original himbo swashbuckler, a precursor to Errol Flynn and Harrison Ford circa Indiana Jones. The reality, though, is that Fairbanks was always a mind at work: he was a voracious reader and an art-obsessed modernist. He watched and championed foreign films in an era when this required significant independent research and investment. He treated his crew like creative collaborators rather than hired hands, lending more artistic license and experimental freedom to crew than was common in Hollywood.

And he put his money and time where his ideals were by co-founding United Artists, an artist-owned rebuke to factory-floor filmmaking of the Hollywood studio system which profited boardrooms rather than creators, and building a blueprint for artist-first control that would reverberate through New Hollywood and the indie boom of the ‘90s. The Thief of Bagdad carries the ethos of artist-driven work in its bones without sacrificing its blockbuster scope.

As much as he was a tireless renaissance man, Fairbanks was also Hollywood royalty with a capital R. Married to fellow silent star Mary Pickford in one of the movie industry’s most illustrious romantic pairings ever (wipes the floor with Brangelina), he presided over “Pickfair,” a Beverly Hills estate and social hub where moguls and geniuses shook hands and compared tuxedo lapels. The carefully cultivated Pickfair luxury was the stuff of gossip column lore: e.g., butlers riding horses through the foyer, peacocks roaming the halls, and bottles of champagne stored in every drawer. But on set, Fairbanks’ reputation was of a workhorse, free of pretension with utmost professional standards. Colleagues consistently described Fairbanks as a cheerful egalitarian when looking back on working with him: he was punctual, disciplined, and happiest when his operation functioned as a well-oiled machine. The star who the tabloids treated as a czar instead behaved like a humble captain, steering the ship with confidence and precision during his glory years. Alas, nothing lasts forever: Fairbanks’ later life was rough. He divorced Pickford, drifted from Hollywood as the talkies took over the theaters, and died in 1939 at just 56 years old. But Thief of Bagdad captures him at full wattage, with inexhaustible charisma and relentless attention to detail.

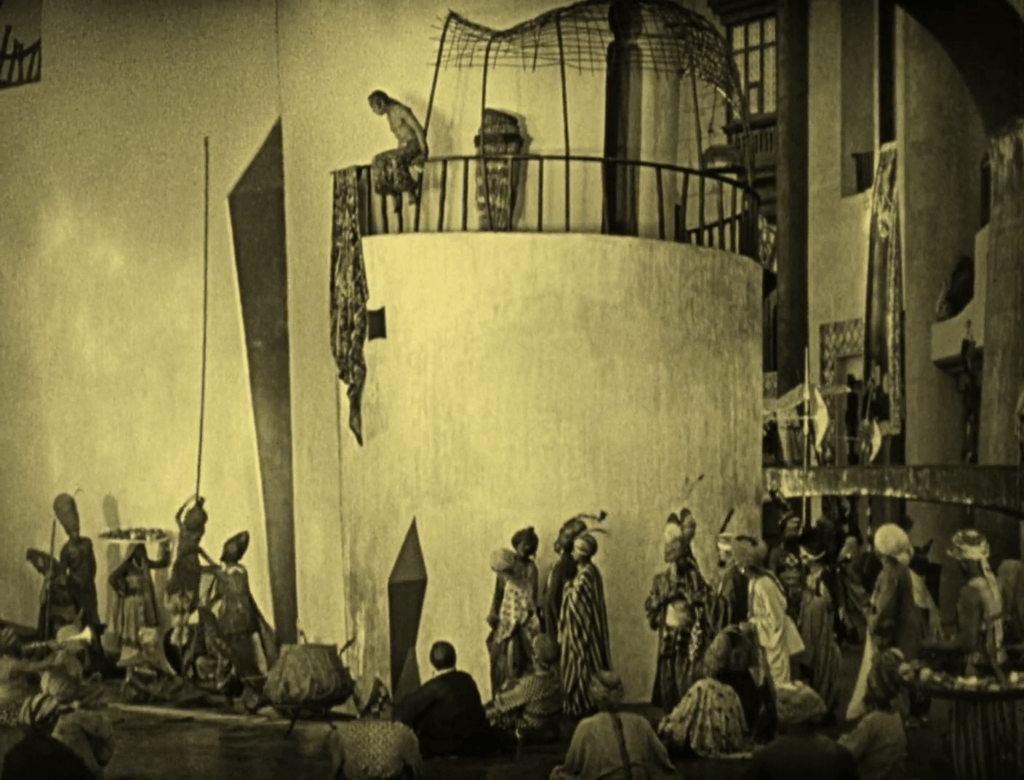

In the film’s opening, we meet Ahmed (Fairbanks), a swaggering thief who swings around the streets of ancient Bagdad like his own personal set of monkey bars, always one jump ahead of the caliph’s city guard. The city is filled with extravagant architecture and movie magic, like ropes that rise through their own power, perfect for quick escapes. Ahmed’s MO at the film’s start is simple, as stated in the intertitles: “What I want, I take.” The setup is already a delight of Fairbanks’ acrobatics, bouncing around market stalls and palace walls. Even moreso, it’s an introduction to the film’s visionary art direction and production design, which was supervised by William Cameron Menzies. The world is immersive and fantastical, almost expressionistic in the vein of some of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’s sets, filled with surprising angles, daunting towers, skewed props, and dreamlike artwork.

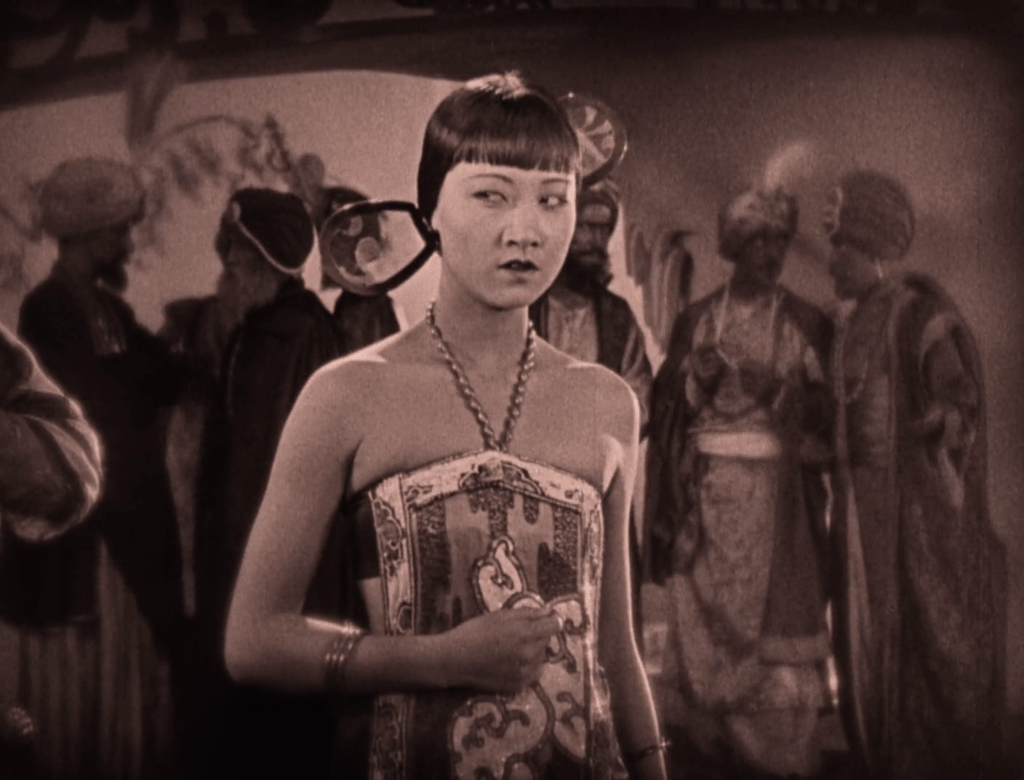

One day, during a palace robbery, Ahmed gets a glimpse of the Princess (Julanne Johnston), whose beauty steals his heart. The Princess is in the midst of being wooed by suitors, including the scheming villain, the Prince of the Mongols (Sojin Kamiyama), who sees the Princess as a way to grab power for himself. Ahmed spies the affair and dresses up like a prince to compete with the other suitors for her affections. He successfully seduces the Princess, and she decides to marry Ahmed among the contenders. But when he confesses his true identity, a servant of the Princess (Anna May Wong) in cahoots with the Prince of the Mongols outs Ahmed, and the caliph whips and banishes Ahmed.

Wong’s performance has become one of the most celebrated aspects of The Thief of Bagdad, even though her role is quite small. Indeed, Wong, the most famous Chinese-American actress of the silent era, is terrifically magnetic and charismatic. Her ability to sell sexy, exotic danger became her calling card thanks to her piercing gaze and enigmatic smile. The precision in her acting conveys a much more modern, lived-in character than plenty of the bigger roles surrounding her. Fairbanks personally cast her after seeing her in some smaller films during pre-production.

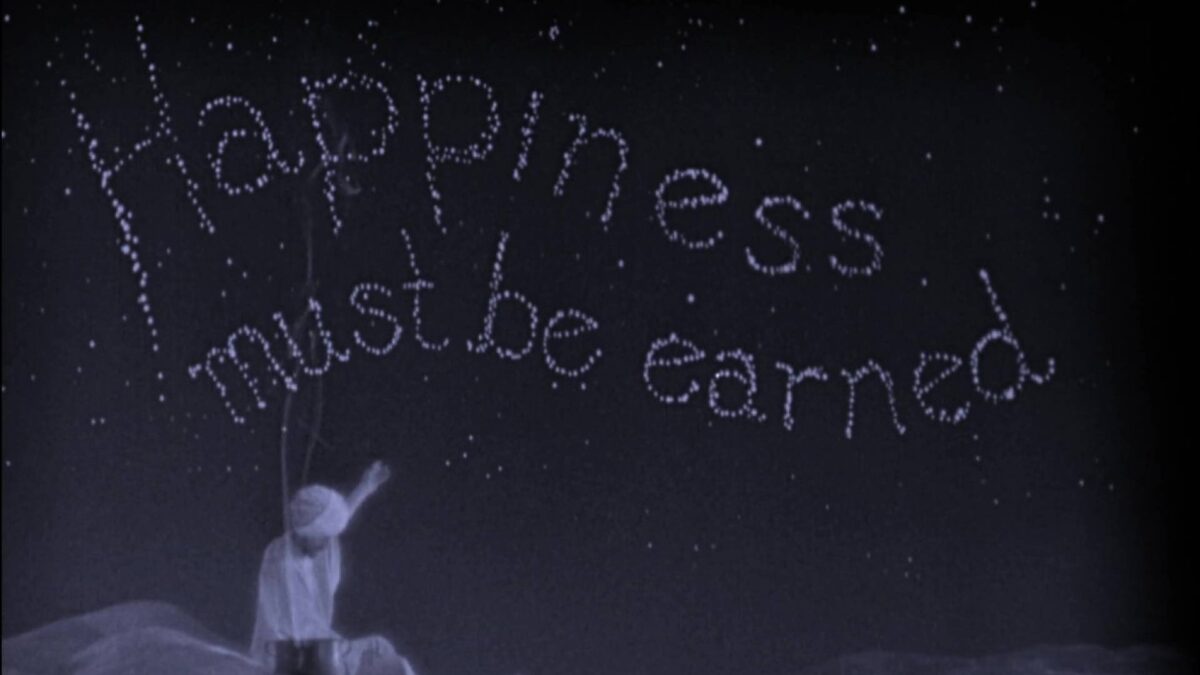

Post-banishment, the wounded, devastated Ahmed encounters a Holy Man (Charles Belcher) who offers the thief some healing wisdom: “Happiness must be earned.” Belcher’s moral guidance leads Ahmed toward a path of enlightenment and transformation instead of deception and bravado. Meanwhile, the Princess declares that whichever suitor brings the most precious treasure to her after seven “moons” will win her hand. When Ahmed sets of on a journey to find some treasure, it’s not only a chance to win the Princess’s heart, but to redeem his soul.

The Thief of Bagdad’s thrilling final act is the promise of the premise, Ahmed journeying through a gauntlet of challenges to gain an invisibility cloak and some magic conjuring powder. He encounters dangerous caves, palaces in the sky, and several fantastic beasts. Meanwhile, the Mongol Prince and the treacherous servant poison the Princess and plot their invasion. Many of the film’s most famous moments, which crystallized and popularized the American vision of “Arabian Nights” aesthetics and imagery, occur during this final third: a magic carpet ride, an epic journey across the desert (here on horseback rather than camel), respites at inviting oases, curved scimitars slaying foes, curve-topped towers encasing alleyway chases. (No lamp or genie in this story, though.) The climax shows Ahmed’s effort to save the Princess against a Mongol army, and it borrows heavily from The Birth of a Nation’s epochal cross-cutting finale to build suspense and energy. (Sans Klan, of course. Incidentally, Walsh appeared as John Wilkes Booth in the film and had a strong relationship with D.W. Griffith.)

That guiding philosophical principle of “earning happiness” is a blend of Fairbanks’ own worldview and a deep reverence for the One Thousand and One Nights. Fairbanks had read a recent translation of the iconic collection of Middle Eastern folktales and studied some art from the region. He became fascinated with the milieu of the Middle East, connecting stories and images to his own life. He worked closely with his crew during pre-production, creating a production bible that connected themes to spectacle such that the visual storytelling would be in harmony with the script: The early segments show the palace in vertical, boxy sets to emphasize the glory and love Ahmed seeks is an enclosed treasure box that needs to be decoded and opened. As he journeys outward, his adventures become more abstract and ethereal, and he sheds pride and worldliness to earn a deeper spiritual enlightenment, which is the real treasure. The final battle with the Mongols is sprawling and chaotic; when he achieves victory, Ahmed soars with his princess on a magic carpet towards the heavens, surrounded only by clouds.

This miraculous set design, some of the best in silent cinema, comes courtesy William Cameron Menzies, the most revered and influential production designer in Hollywood through the 1950s. In fact, Menzies is credited with coining the term “production designer” in the 1930s as a new and specialized discipline that brings a practical element to “art director,” which is his official credit in Thief of Bagdad. Menzies’ most famous work comes from the Gone with the Wind 15 years later, where he was one of the few voices that David O. Selznick would defer to, and for which he won an honorary Oscar. But Menzies rarely had a bigger and more impressive than he did on Thief of Bagdad, where he brought grand, experimental Art déco visions to life, completely shaping the film’s texture. Palace gates, yawning arches, and towering walls fill the sets with extravagance, decorated with textured patterns and Bauhaus-style geometric shapes. The princess’s quarters are draped with translucent fabric that looks like a flowing fountain, its shell-like base cradling the princess, evoking The Birth of Venus. The caliph’s throne room puts The Iron Throne to shame, a massive pedestal with ornamentation like a pipe organ or Luray Caverns. Every frame of The Thief of Bagdad is a busy and rich visual treat thanks, in large part, to Menzies’ work.

While Fairbanks was the architect and leader of the project, and Menzies its artistic visionary, Raoul Walsh (more known deserves much credit, too. The Thief of Bagdad was the only feature film on which Fairbanks paired with Walsh, but Walsh proves a great fit for this style of project. He perfectly frames Fairbanks’ exploits and Menzies’ sets such that they’re exciting to watch and easy to follow. He also demonstrates a terrific command of scale and large on-screen casts. Late battles featuring hundreds of extras are not quite as masterful as the Fairbanks acrobatics set pieces, but they are epic and wonderfully staged by Walsh.

Mortimer Wilson composed the original Thief of Bagdad score. Wilson, like Menzies, was given unusual artistic freedom and empowerment for the era. Fairbanks hired Wilson to compose a completely original score for the film, which was unusual for the era. But Fairbanks acknowledged the score as a key component of the film’s artistic soul and gave Wilson then-unprecedented participation in the film’s creation. Wilson viewed footage within days of it being filmed, composing to each scene and mood shift, building a musical language of leitmotifs and developing themes over the runtime. Directors of the time typically viewed scores at the time as equivalent to sound effects — something to accent each event on screen, mainly to play up the film’s biggest moments. Fairbanks encouraged Wilson to make a more holistic composition rather than a series of stingers and anthems. The result is a balance — a score tightly coupled with the film, but also one that stands and functions on its own as a piece of music.

If that latter description sounds like what you expect a movie score to be, you’re not alone. Per Fairbanks biographer Jeffrey Vance, the Thief of Bagdad score by Wilson is widely regarded as a milestone, one of the works to crystallize the modern form. Sound technology and standards would change over the ensuing decades, but musicologists turn to the collaboration between Fairbanks and Wilson in this film, Don Q, Son of Zorro (1925) and The Black Pirate (1926) as foundational to modern score composition. The score is on Spotify. I confess, to my ears, it sounds like a solid but generic action-adventure score. I think that’s a byproduct of its influence, though: When a creative work becomes a standard-bearer, it can seem less bold years later within an ecosystem saturated with work built upon it.

The film has been restored and distributed many times in the home media era. In the 1980s, Carl Davis arranged a new score for the film with more of an Eastern music flavor, largely adapted from the great Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The Kino Lorber Blu-ray release of the film, the one I own and the definitive release as far as I can tell, includes the Davis score, and, per Vance, it has replaced Wilson’s as the definitive score for the film. Because the film is public domain, it’s easy to find streaming versions of the film with Wilson’s original score, though. (For example, it’s on YouTube.) The next time I watch The Thief of Bagdad, I will watch a cut with the original Wilson composition.

The Thief of Bagdad is no longer a movie night staple, which is a shame. (It has 13k logs on Letterboxd, compared to Barbie as The Princess & the Pauper’s 335k.) But that doesn’t mean it has vanished by any stretch. Its influence, particularly in “Arabian Nights” aesthetics, reverberated for decades and into the present. You can draw a line from this film to Lotte Reiniger’s Adventures of Prince Achmed, onward to the Technicolor dream of Korda’s 1940 The Thief of Bagdad, a remake of sorts. George Lucas pulled inspiration directly from this film in his design of Tatooine in Star Wars, and from that you can find some Fairbanks DNA in hundreds of blockbusters, including Denis Villeneuve’s Dune movies. Segments and shots of Disney’s Aladdin are ripped whole-cloth from this film, including the guard-dodging chase that opens both films and the imagination-capturing magic carpet flights.

Even aside from its specific aesthetic and artistic legacy, The Thief of Bagdad’s pricey production also influenced the making of big-budget barn-burners for years to come. Fairbanks’ production became a model of well-organized ambition, where big investments into world-class talent yielded box office returns and critical respect. Thief also raised the bar on special effects. It brings together the cutting edge on all effects of the time: Melies-esque camera tricks, shifting the camera cranking speeds to create more dynamic speed of motion, compositing, mattes, animatronic creatures, carefully-concealed wires and props to enhance the acrobatics, etc.

A film of this nature will inevitably bear questions and criticisms about its representation and cultural appropriation. Certainly a film made in 2025 would tackle this story differently. Some of the film’s elements have bad optics: Two of the people of color in the cast are the villains, for example, and the production is led by white American artists mimicking and synthesizing Asian art influences with their own styles. It’s a film in line with the Orientalism that was popular from the turn of the century until World War 2. But I give the film the benefit of the doubt for a couple reasons: First, the film’s production and story are so firmly in fairy tale mode, it never comes across as belittling or stereotyping of any contemporary people, much the same way Disney’s Hercules never registers as depicting Greek people from the 1990s. Second, Fairbanks approaches the material with respect and admiration, and that carries in his adaptation. His cast and crew include several people of color, including one of the two writers, Achmed Abdullah from Afghanistan. None of the characters, even the villain, ever function as cheap caricatures. While not free of exoticism or dated language or images, The Thief of Bagdad plays more like cultural pastiche than theft, unlike plenty of films filled with racism and yellow- and blackface of the ‘10s and ‘20s. If you can stomach Jafar in Disney’s Aladdin, The Thief of Bagdad should be palatable, too.

My one big mark against the film, and the reason I reluctantly hold it just a hair below a Masterpiece rating, is the matter of pacing: The Thief of Bagdad is nearly two and a half hours long, and the real quest doesn’t start until more than halfway into the film. I’m not entirely sure what, if anything, I would actually trim, as it’s pretty much all good. But, you do feel the rhythm drag just a little in a way that it would absolutely rip if it were closer to 90-100 minutes instead.

Douglas Fairbanks would continue his timeless, pioneering work in the years to come. The Black Pirate from two years later was the first-ever Technicolor wide release, though its two-strip coloring is muted relative to the three-strip technology that we associate with the likes of The Wizard of Oz. And Fairbanks as an icon is probably best remembered for his performances as Zorro, giving the US masses a perfect icon for the Z-slashing hero. But for sheer artistry and movie magic, Douglas Fairbanks would never surpass The Thief of Bagdad, one of the great adventures in all of cinema.

Is It Good?

Exceptionally Good (7/8)

Dan is the founder and head critic of The Goods. Follow Dan on Letterboxd. Join the Discord for updates and discussion.

5 replies on “The Thief of Bagdad (1924)”

One can proudly say that I saw THE THIEF OF BAGHDAD and the original BEN HUR (No, not that one, the black and white one) in theatres – or it may have been a concert hall – having been taken by my dad to see a … I think the proper term is revival? … lo these many years ago.

Before THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING, even! (In fact it’s amusing to note that these might well have been the first Epic Films I ever saw on a cinema screen).

It says something that I can remember bits and pieces from both films the better part of three decades later (Also that Douglas Fairbanks Senior remains a name to conjure with even a century after his heyday – and it’s interesting to wonder if Mr Tom Cruise consciously thinks of himself as following very much in Mr Fairbank’s footsteps, because there are a number of interesting parallels).

I’m super envious of seeing this on a big screen (or for that matter ANY silent film).

Now that you suggest it, I think you’re right that late era Cruise does fall in the Fairbanks lineage: A much-appreciated craftsman/stuntsman who is a brand unto himself, producing and guiding the movies he stars in; maybe not as much as Fairbanks, but still clearly “his” movies. Top Gun Maverick = Thief of Bagdad???

To be precise it wasn’t a modern Big Screen – this was in a concert hall rigged up as a movie theatre, rather than a purpose built cinema – but in all honesty that just added to the retro charm.

Man, wish I could see this in a theater sometime.

But yeah, this is really quite great. (I will agree on the pacing, with the caveat that it’s a combination of pacing and dreaminess and being a silent film in the first place. But although I have no unpleasant sensation at all associated with it, I have *definitely* lost consciousness watching it.)

This and Black Pirate are awesome. Zorro’s also pretty good. The rest, uh, well, either way, Fairbanks’s action hero legacy is secure for all time.

I was excited to see this among your tens. “Dreaminess” is an element of this I don’t think I properly emphasized in my review, but I think you’re spot on. I confess I probably wasn’t in a place to use all the superlatives I did here given that I’ve only seen portions of Fairbanks’ other movies. But I watched over half of Black Pirate a couple days ago and was definitely hooked.